COVID-19 and Ageism: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

By Karen C. Rose, Ph.D.

By Karen C. Rose, Ph.D.

Age-Friendly University Champion

Adjunct Professor of Health Sciences and Psychology

The COVID-19 pandemic has given our nation unprecedented challenges that continue into a second year. Less obvious, it has also given us an unprecedented opportunity. As the pattern for hospitalization and mortality rates show that older adults (>65) in the United States were disproportionally affected by the coronavirus (CDC, 2019), there is a unique opportunity to reflect on the national response to the needs of the nation’s oldest citizens. A recent review, (Monahan et al., 2020) finds evidence of varied responses toward older adults in the face of this national crisis: positive responses, unintended negative consequences of positive responses, and ageist and negative responses. Here, we reflect on what could be perceived as the good, the bad and the ugly, and how both positive and negative responses are important to moving forward once the pandemic is behind us.

Positive Responses to Older Adults during the Pandemic (The Good)

Positive Responses to Older Adults during the Pandemic (The Good)

Early in the pandemic, many communities instituted policies to limit the exposure of older adults to the virus. For instance, stores offered early morning hours for shopping that were meant to limit crowd exposure and to ensure entry after the store had been thoroughly cleaned. Loved ones and community organizations stepped up to provide home deliveries of food, medications and other essentials. Even older adults (>65) most impacted by the virus showed support through virtual volunteer efforts. To combat the negative effects of isolation, nursing homes began video calls or scheduled window visits with loved ones, and intergenerational programs designed to connect older adults with children and high school students through letter writing and pen-pal programs flourished.

These examples are illustrative of the best in us. Based on an extensive body of research, supportive behaviors such as those shown during the crisis have potential to impact not only physical health as was intended, but also to impact mental health by increasing feelings of self-worth, social connectedness, and communicating to older adults that they are valued and respected members of a community. In addition, intergenerational opportunities prompted by the crisis have potential to lead to more positive perceptions of aging and older adults, better understanding of the aging process, greater empathy toward challenges facing older adults, and recognition of similarities despite age differences. Extensive research demonstrating the effectiveness of intergenerational service-learning programs on attitudes and behavior toward older adults supports this prediction (see Levy, 2018; Burnes et al., 2019).

Unintended Negative Consequences of Positive Responses to Older Adults (The Bad)

Well-meaning intentions designed to slow the progress of the virus appear to have had unintended negative consequences for everyone—but especially for older adults. Social distancing creates potential for feelings of social isolation and loneliness; distancing from family, community social networks and places of worship were particularly difficult for older adults whose social networks tend to be smaller than those of younger adults. It is well-documented that isolation and loneliness can increase mortality and risk of dementia and negatively influence other mental and physical health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, risk of heart disease, rehospitalization and negative health behaviors such as smoking and drinking (Nicholson, 2012).

For older adults in assisted living and nursing homes whose risk of exposure to COVID was heightened, social distancing and isolation exacerbated the effects of the virus. Interactions with family members who often serve as patient advocates were limited, decreasing the chances of noting changes in a resident’s health. Staff shortages and limited peer interactions further reduced health monitoring.

In the long-term, social distancing and stay-at-home orders also have potential to impact long-term job security and economic security for older adults. There has been a 7% increase in early retirement since the pandemic and why is unclear. It may be because of heightened fear of health and safety concerns in the work environment, lack of opportunities for teleworking, or expectations of future age discrimination. What is known is that early involuntary retirement has potential to impact health and decrease lifetime earnings.

Ageist and Negative Responses to Older Adults during the Pandemic (The Ugly)

Ageism is described as prejudice and stereotypes attributed to older adults based solely on age (Iversen et al., 2009). It is complex, with at least three interrelated parts: prejudicial attitudes toward older adults and the aging process; discriminatory practices based on age as seen in the workplace and in other social roles; and institutional practices and policies which have potential to perpetuate stereotypes about older adults, reduce independence and undermine personal integrity. To be fair, ageism is neither new nor is it a product of the pandemic. What is of concern is that the pandemic revealed potentially harmful discriminatory practices, unleashed new prejudicial attitudes, and reiterated and reinforced stereotypes about older adults.

One of the most concerning of potentially discriminatory responses toward older adults occurred in health settings. As health care systems and resources became stressed, health care providers were forced to triage medical resources. China and Italy, overwhelmed by limited resources and supplies earlier than the United States, implemented medical triaging that used age as a criterion for life-saving treatment resources regardless of prior functional health--this is a worrisome precedent. Similarly, the response of trusted health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMMS) to the crisis seemed to be unusually slow given the speed of virus spread.

Although it was clear that there were many COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes by early February 2020, it was not until mid-March 2020 that the CDC recommended long-term facilities and nursing homes restrict visitors and limit recreational activities. More stringent recommendations including screening of visitors into the facility, temperature checks and PPE came later in April 2020 (CDC, April 2020). The slow pace of the response to a pandemic that was disproportionately affecting older adults prompted Louise Aronson, a respected physician, geriatrician, educator and writer to ask in a New York Times editorial: Why are we OK with Old People Dying? (Aronson, March 22, 2020)

Ageist stereotyping through media messages that depict older adults as frail and vulnerable (Abramson, 2020) were also apparent throughout the pandemic. Although it is true that those 65 and older are vulnerable with respect to greater risk of complications from the virus, it does not mean that those 65 and older are frail and vulnerable. Pairing >65 and vulnerability in the messaging as some media outlets did has potential to conflate the relationship and to reinforce the stereotype. In fact, there is evidence of the contrary, as older adults showed better coping with the mental health challenges of COVID-19 than younger adults (Cartensen et. al, 2020).

What Can Be Learned?

What Can Be Learned?

Early reflections on the crisis suggest that there were both positive and negative responses in the treatment of older adults through the COVID-19 pandemic. Positive responses grew in response to the crisis and now is the time to find ways to sustain those efforts across health, educational and business settings. On the downside, negative responses highlight a need for clear and fair health policies that consider short-term and long-term survival in triage decisions with the use of age as a secondary consideration.

They also highlight a need for fair and balanced employment policies that consider the potential for age discrimination in the tools used to stem pandemic effects such as furloughs, reduced pay, layoffs, rehiring and retirement. Finally, and most relevant to educators, is the need to address ageist attitudes and stereotypes that have potential to worsen because of the pandemic. There are over 48 million older adults who did not die during the pandemic and many who will become part of this older group in the near future. Calling out bias and finding ways to address it will be important to the memory of those who lost their lives and to those who live.

Why is the last point especially relevant to students and educators and to Stockton University? Because it is what we do and have been doing well before COVID-19. As part of the Age-Friendly University (AFU) initiative, we are a member of a growing global network that views universities and colleges as integral partners in building age-friendly communities, combating ageism, and offering a place to begin at a grassroots level.

Through classes, programming and supporting offices, we strive to provide opportunities and support to students, regardless of age. This is an unprecedented opportunity to use our expertise to create novel approaches to sustain and expand positive responses and to address negative responses laid bare by this pandemic. Are there novel interdisciplinary initiatives that could be developed to reduce ageism in broader settings such as health care and business? Are there novel approaches to fostering connection and solving post-COVID concerns of older adults in the community? Now is our time to lead.

Read the World Health Organization's Global Report on Ageism for more information.

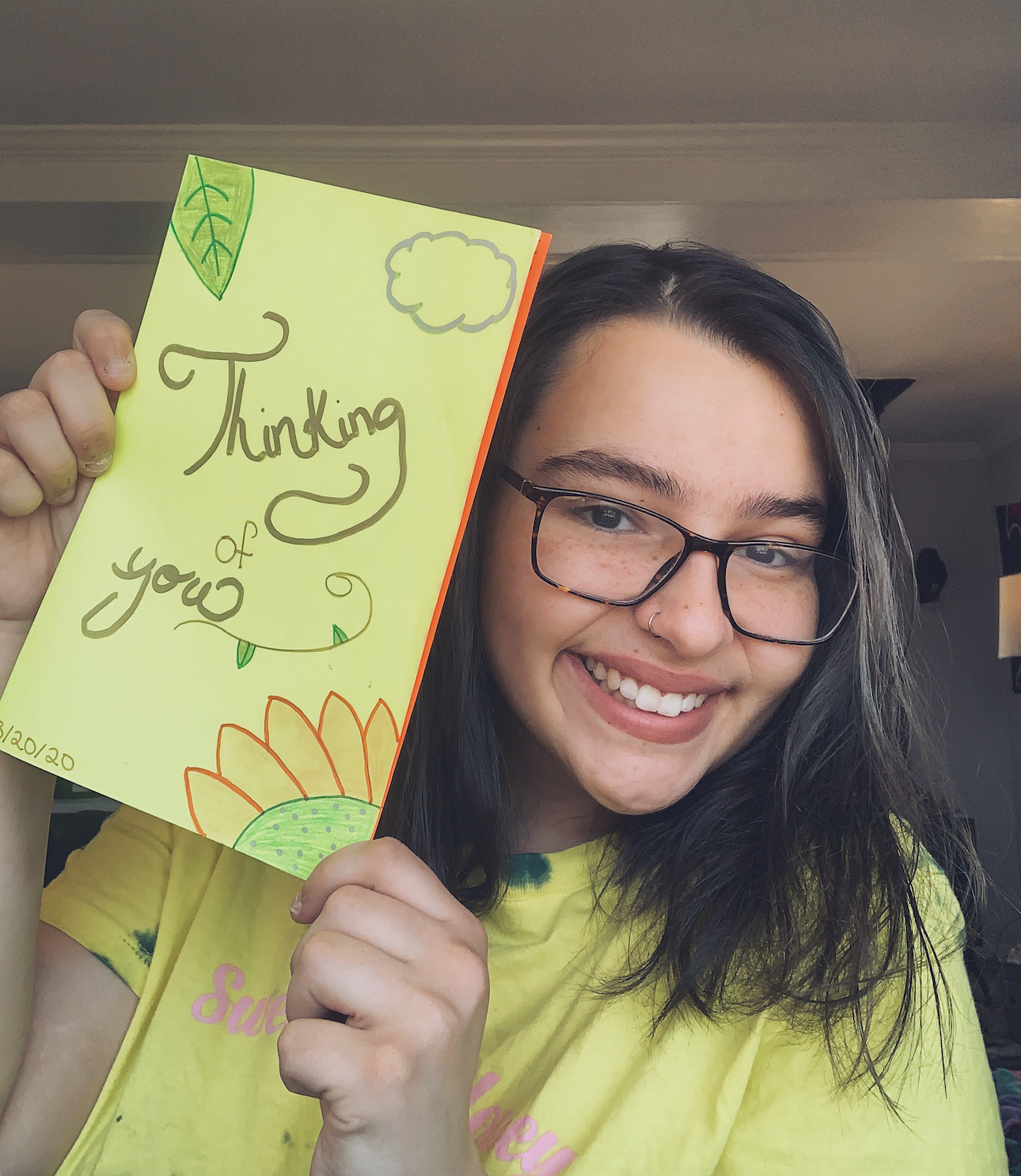

Photos: Stockton students in the Gerontology minor and club sent cards to Seashore Gardens Living Center resident Frank on his 88th birthday when they found out his family couldn't be there in person to celebrate in April 2020.