Picture Stockton...Using Art to Save Birds

A flock of birds has taken flight in artistic form across the K-Wing breezeway on Stockton University's Galloway campus to warn migrating birds to steer clear of the windows.

To a soaring songbird, reflections of sky and forest on glass are indistinguishable from the hard reality. Building collisions are one of the top anthropogenic threats to birds, causing up to one billion bird deaths annually in the U.S. according to scientific estimates.

The K-Wing breezeway, located between Lake Fred and the Campus Center, is an especially dangerous spot because it is an expansive, double-sided window space adjacent to prime bird habitat in the Pinelands National Reserve.

To reduce bird strikes on campus, a vinyl mural now raises awareness with its message, "Art should be striking. Not birds," along with an explanation of how the art saves birds by eliminating reflections.

The solution was a collaborative effort between Stockton's School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University Relations & Marketing, the Division of Facilities & Operations and the Biodiversity Committee with funding provided by the President's Office.

No one is more familiar with campus bird strikes than John Rokita '78, assistant supervisor of Academic Lab Services, who has recorded data on 851 windowkills from 1979-2018, preserved hundreds of specimens through taxidermy for educational purposes and rehabilitated thousands of birds that survived impact.

Rokita first became aware of the issue as a Biology major when he and fellow student Lester Block, who works in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, monitored the campus to quantify bird strikes.

Stockton’s earliest study of bird-window collisions was published by Jeffrey Sherman as a student project for Professor Mark Pokras in 1978.

"It began with finding injured birds and taking them to instructors Mark and Martha Pokras for medical attention and rehab. I made the study for my senior project mapping the most prominent areas of concern and types of species. I walked around the campus almost every morning for two years to collect data. Lester Block and John Rokita helped and eventually took over the project as I graduated," Sherman, now an anatomy and physiology teacher, explained in an email.

When Sherman heard about the mural concept, he said, "It made my day that I had some kind of impact from a long time ago."

The mural came to life over the past year as many campus employees combined their talents.

Photos and story by Susan Allen

Note: Susan Allen works in University Relations & Marketing and was awarded grant funding for the project through the 2020 Strategic Plan. Over the past decade, she has documented window collisions, bird rehabilitation efforts, Stockton's taxidermy collection and the process of designing a solution. She shares the journey through her eyes.

Unsuspecting birds in flight don't slow down or make a hard turn as they approach expanses of windows that reflect the sky and surrounding habitat. Fooled by the reflections, they are completely unaware that they are about to strike a hard surface.

A Hermit thrush lies dead on the ground next to a window it struck during fall migration. Luckier birds that are stunned by window strikes are picked up by caring hands of observant passersby and delivered to John Rokita for rehabilitation.

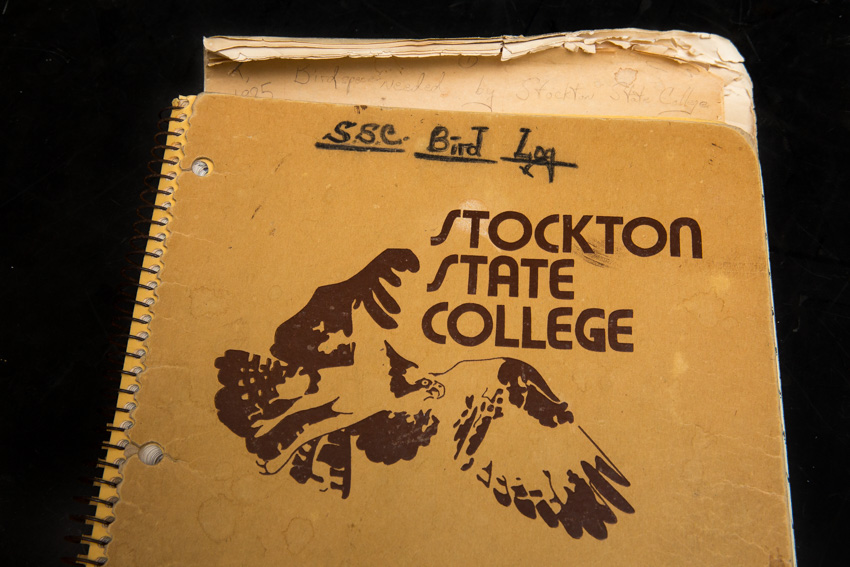

A 150-sheet notebook documents dead birds that are reported to Stockton's Animal Lab. Entries begin in 1979 and note the date, species information, location found, cause of death and how the specimen was preserved.

Warblers

Woodpeckers

Peregrine Falcon

Passenger Pigeons

The art of taxidermy allows birds to live on as educational study skins. The preserved specimens, many made from window-kills, bring a variety of local species into the hands of students for observation. Pictured are shelves of warblers and woodpeckers in Stockton's taxidermy collection. The immature peregrine falcon banded with code B64 was recovered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after it struck a Boston skyscraper. The preserved passenger pigeons, now extinct, were donated to Stockton and give students a rare glimpse at a lost species.

Students can feel the textures of feathers and examine fine details with study skins that are used educationally for class presentations and for birding identification workshops for participants in the Pinelands Short Course. Pictured are the feathers of a male Ring-necked pheasant.

Stunned birds still have a chance to survive. In some cases, a warm, quiet place and some nourishment are enough to help them regain their strength. Pictured are a Ruby-throated hummingbird, American woodcock, Hairy woodpecker and a Tufted titmouse that received care from John Rokita and student workers in the Animal Lab.

Motivated by her passion for birds and conservation, Alice Sikora, of the Office of Institutional Research, volunteered to transform decades of data entries in a notebook into an online spreadsheet to identify high impact locations and peak months for window collisions on campus. Sikora is determined to ensure that bird strikes aren't seen as "invisible deaths" and is inspired by Rokita who she calls a "quiet hero" for the work that he does behind the scenes to protect and educate others about wildlife. Sikora and Susan Allen presented the data to Stockton's Biodiversity Committee and worked with Cynthia Gove to coordinate plans with Facilities & Operations. Christopher Deets '99, '00 works as an outreach and education coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Migratory Bird Program and provided Stockton with best practices and guidance.

Haunted by the sounds of birds crashing into his art studio windows, Jacob Feige, associate professor of Art, began making his own hawk decals. “Every October I brace for the thud of south-bound birds on the north-facing windows of the painting studio at Stockton. I regularly cut bird shapes out of black paper and tape them to the windows. It has significantly decreased the number of dead birds on the outer window sills during the fall migration,” he explained. Stockton graduate Kevin Villalona did an independent study project with Feige to get real-world design experience by mocking up a concept for the breezeway.

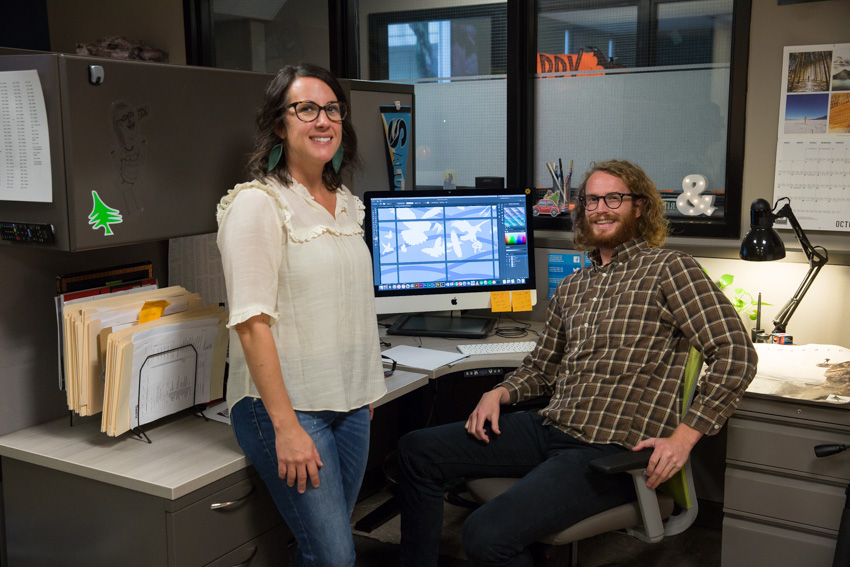

Graphic designers Heidi Hartley and Bernard DeLury show the Photoshop template they built to mimic the K-Wing breezeway dimensions and layout. They combined their creative talents to fill the window space with a variety of bird species and other winged creatures like butterflies and dragonflies in a soaring wave that moves across the windows like a flock of birds.

The design was printed on perforated film and adhered to the exterior glass to block reflections on both sides of the breezeway. Those walking through the breezeway can see an unobstructed view of the outside. Viewers from the outside see an educational mural and birds in flight are re-directed to avoid the windows.

The mural continues onto the side of the breezeway facing the Campus Center. Share your view of the artwork and help to spread awareness by using the hashtag #WingsAwayFromWindows on social media.

Ornithology with Daniel Hernandez

Ornithology with Daniel Hernandez

Daniel Hernandez, associate professor of Biology, teaches an Ornithology course that takes students outside to go birding. Stockton's mural now extends discussions into conservation actions and stands as an example for others to be inspired.

A sample of study skins that were made from window-kills are displayed to illustrate the diversity of species and sizes that are affected by window collisions. Starting in the middle of the spiral are Ruby-throated hummingbirds and at the end are a Sharp-shinned hawk and a pair of Ruffed grouse.