New Book Details Expedition to Map the Walker Wreck

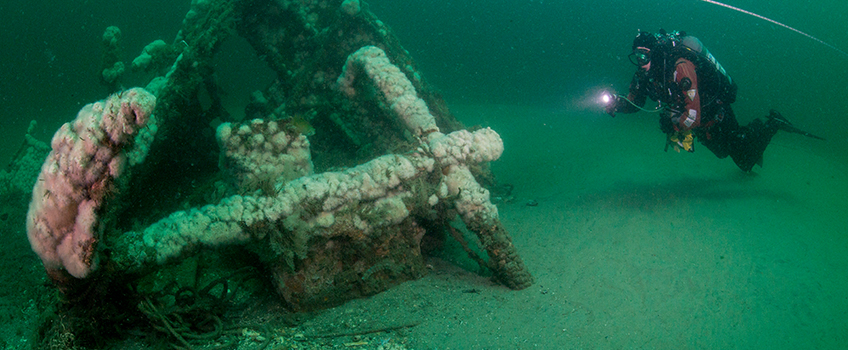

A diver explores the Robert J. Walker shipwreck. Credit: Stephen Nagiewicz

Galloway, N.J. - Stephen Nagiewicz was “collecting wrecks” as a diver in the 1990s when he first visited the $25 wreck, also a good fishing spot, nicknamed for how much a fisherman paid for the shipwreck’s coordinates off Atlantic City.

Galloway, N.J. - Stephen Nagiewicz was “collecting wrecks” as a diver in the 1990s when he first visited the $25 wreck, also a good fishing spot, nicknamed for how much a fisherman paid for the shipwreck’s coordinates off Atlantic City.

That initial visit was “just another dive,” but after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) identified it as the long-lost Robert J. Walker shipwreck, Nagiewicz went back in 2014 as part of an official mapping collaboration with the Stockton University Marine Field Station, the New Jersey Historical Divers Association and NOAA.

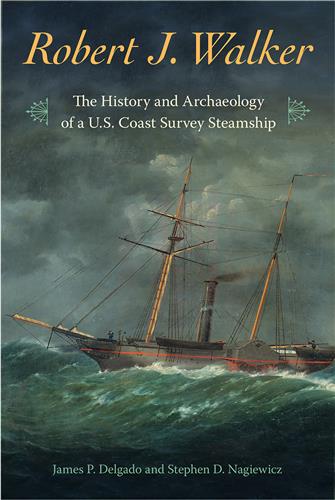

Nagiewicz, an adjunct instructor at Stockton, a certified archaeologist and a teacher at Atlantic City High School, and James Delgado, a maritime archaeologist and historian, co-authored a book, “Robert J. Walker: the History and Archeology of a U.S. Coast Survey Steamship” detailing the expedition to map the wreck. Peter Straub, dean of the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, also contributed a chapter.

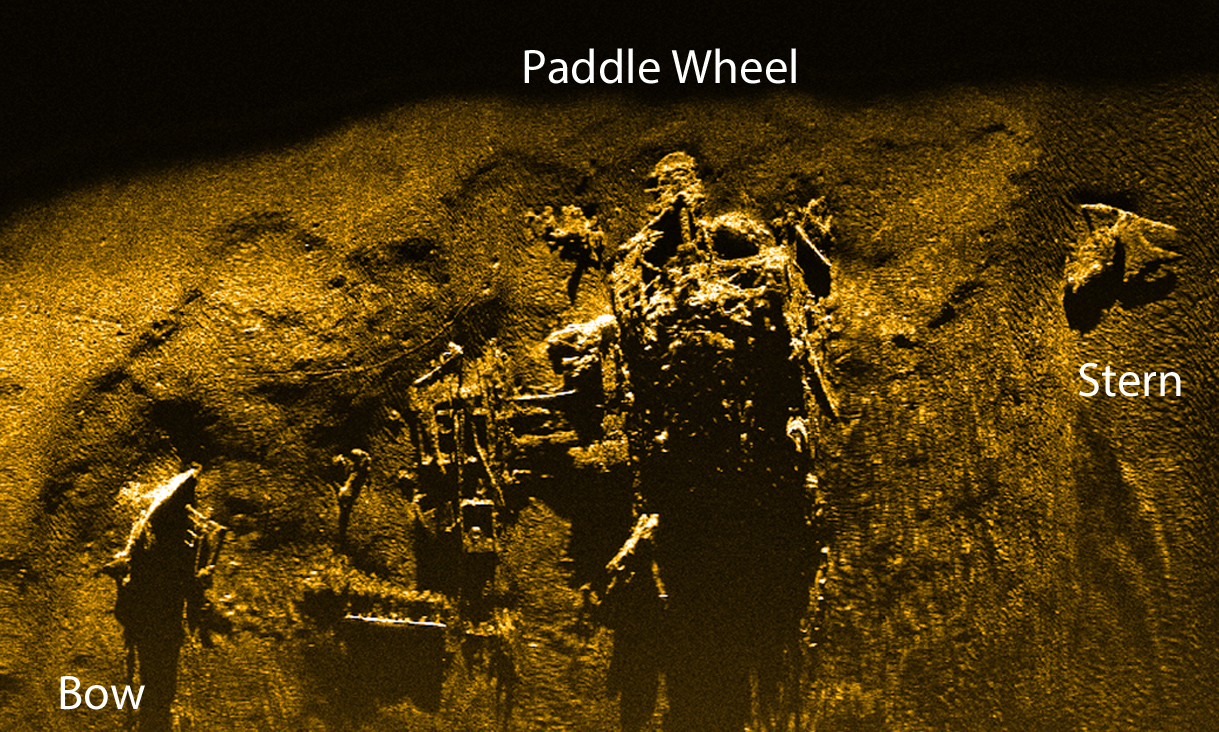

The Walker collided with the schooner Fanny and sank on June 21, 1860, “which would 150 years later become World Hydrography Day, which was the business of the Walker—a coast survey ship doing hydrographic surveys around the country,” Nagiewicz explained.

The paddle steamer surveyed 17,942 miles of coastline in its 12 years of service that ended in tragedy with 20 lives lost in the greatest loss of life at sea in the history of the U.S. Coast Survey.

Right after Sandy, “NOAA was there surveying the coast for New Jersey to see where all the trash from the hurricane might have wound up in the shipping lanes,” he explained.

NOAA historians pointed out that the Walker supposedly sunk off Atlantic City and encouraged surveyors to look while they were in the area. The Walker is not alone under the sea. “There are several paddle wheelers believe it or not within 10 miles of each other in that spot,” Nagiewicz said.

Robert J. Walker was Treasurer of the United States and tasked Coast Survey officers to find the Fresnel lens for Absecon Lighthouse, which was the only light that could have been seen on the stormy night when the ship in his name sunk. That light is “where they were headed before they sank.”

Looking out from the top of Absecon Lighthouse, the state’s tallest lighthouse, the wreck lies to the southeast offshore of Ocean Casino.

Nagiewicz first learned of the Walker from James Delgado at a lecture that sought help from local divers to assist NOAA in a mapping effort that led to the Walker being recognized on New Jersey’s National Parks Register of Historic Places.

“It was because of Steve Evert and Peter Straub that Stockton became involved. They were willing to commit their resources,” said Nagiewicz.

Students in Peter Straub’s Summer Intensive Research Experience (SIRE) had the unique opportunity to help map history in 2014.

“The mapping was a community archeology event where local people had a hand in mapping their own maritime history,” said Nagiewicz.

More than a dozen divers went underwater with yard sticks and tape measures and recorded their

measurements on slates. Over the course of a week, about 3 terabytes of photos and footage were captured and the wreck dimensions were mapped.

More than a dozen divers went underwater with yard sticks and tape measures and recorded their

measurements on slates. Over the course of a week, about 3 terabytes of photos and footage were captured and the wreck dimensions were mapped.

“The mapping was a community archeology event where local people had a hand in mapping

their own maritime history,” said Nagiewicz.

A report was made for NOAA, and the community archeology aspect became Nagiewicz’s Professional Science Master’s capstone project that he presented at the Society of Historical Archeology in Washington.

A square port hole, one of the first clues that identified the Walker, now lives in the main lobby of the John F. Scarpa Academic Building in Atlantic City in a kiosk display.

Students who are interested in diving can take Nagiewicz’s Underwater Science and Technology general studies class that includes an optional scuba introduction at Ocean City Municipal Complex’s pool. His Impact of Shipwrecks on New Jersey Maritime History class allows students to hold history in their hands.

Nagiewicz was honeymooning in the Bahamas when he took his first dive. Now, 4,000 dives later, he is sharing and teaching maritime archeology, history and technology.

Reported by Susan Allen

Alumni Spotlight

Alumni Spotlight