National Science Foundation Grant Helps Stockton Study Inlets

Galloway, N.J. - Anna Pfeiffer-Herbert, associate professor of Marine Science, studies the exchange of water between the ocean and the bay through inlets. This summer, she and a team of research interns are looking at the two inlets flanking the 18-mile stretch of Long Beach Island with funding from a $155,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

Pfeiffer-Herbert, who grew up in Acme, WA and now resides in Galloway, uses a simple analogy to explain the importance of understanding how long it takes water to exit the bay through an inlet.

Imagine a toilet or a sink. If you never flush it out, the water will get stagnant. If that happens in the bay, things will start to grow. A lot of nutrients are coming in from land drainage and if excess amounts of nutrients are staying in one place, they cause excess organic matter to decompose and that can clog up water systems and decrease oxygen in the water," said Pfeiffer-Herbert.

The flushing rate in the bay impacts the health of the ecosystem that wildlife and humans depend on for habitat, recreation, commercial fishing and ecotourism.

The combination of a data set that describes water quality and a data set that describes how fast water flushes out of the bay at two different inlet types allows researchers to better understand how inlets work.

The research team is working with the Stockton Marine Field Station to collect water velocity and water quality data at both inlets.

Six Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs), one in Barnegat Inlet and five at Little Egg Inlet, sit on the bay floor and record water velocity and direction. Conductivity Depth Temperature (CTD) sensors are deployed at the six research sites to capture water quality data and are connected to large floating buoys.

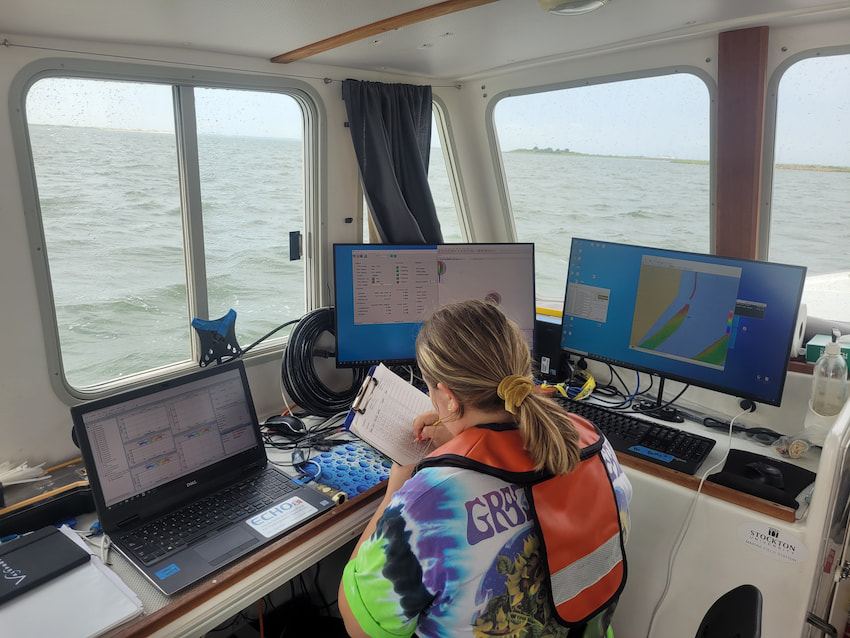

Steve Evert, director of the Marine Field Station, and Nate Robinson, Marine Field Station assistant, conduct seasonal surveys where they pull a boat-mounted ADCP with the R/V Petrel along set lines for the duration of a full tidal cycle (about 12 hours of mapping) at both inlets.

Lessons Come To Life on the Water

Undergraduate students get the chance to bring their textbook lessons to life on these survey trips.

Students collect water quality data with a handheld CTD instrument that is lowered into the water via a rope.

Kyle Dantas, a sophomore Marine Science major, is intrigued by how the ocean influences Earth’s climate and plans to go to graduate school to study climate change. He got involved in Pfeiffer-Herbert’s research because he wanted an opportunity to “get my hands dirty and learn precisely how things work.”

Field Work Prep on the R/V Petrel

Dantas felt just how dynamic the ocean can be during a survey that took place after a passing storm. The winds resulted in choppy water and that was felt in the rocking from the boat, he recalled.

The research opportunity gave Katelyn Seay, a senior transfer student majoring in Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Biology, her first boating experience. “I loved it,” she said.

Seay was on two morning surveys where she used the CTD to collect data.

Sharks captured first-year student Samantha Gransee’s attention from a young age and guided her to choose Marine Biology as a major. Gransee helped to assemble the tripod structure that the ADCP sits in on the bay floor and was on a survey where she saw how the side-mounted ADCP is deployed.

Nicole Ertle, a Marine Science graduate currently in the Coastal Zone Management master's program, Jessica Nanni, a Marine Science graduate, and Caroline Linton, a Marine Science major, are also working on the project this summer.

Armored Versus Natural Inlets

Although they are neighboring inlets, Little Egg and Barnegat represent two extremes. Little Egg Inlet, just south of Holgate, is undeveloped. “It’s allowed to change at will. The sandbars move and the shape of the bottom is constantly in flux. All inlets used to be like this, but now few are left,” Pfeiffer-Herbert explained.

Barnegat Light Inlet, which separates the north end of Long Beach Island from Island Beach State Park, is armored to stabilize the inlet from natural changes. Jetty rock barriers along the edges stabilize the width and twice-annual bottom dredging keeps the navigational channel deep enough for commercial fishing vessels and the U.S. Coast Guard.

Geometry and Seasons Dictate Water Flow

Incoming and outgoing tides last about six hours each, but geometric factors like depth, width and cross-sectional area as well as the water elevation in the ocean versus the water elevation in bay and sometimes winds, dictate how fast water flows.

“A big water level difference will generate a faster water flow, but if the inlet is small, water has a much harder time passing through and will increase the flow rate, but restrict the total volume of water that can flow through,” Pfeiffer-Herbert said.

Inlet function changes with the seasons. “We are trying to measure what we are hypothesizing from prior research. In the summer you have good conditions for growth and decomposition and probably slower times for the bays to flush. We are investigating how that flushing time changes with the seasons,” Pfeiffer-Herbert explained.

Models Offer Predictions

The detailed information describing the inlets will be entered into expanded computer models to predict all of the system—the inlets all the way up into the rivers.

A prior study by the U.S. Geological Survey created computer models of Barnegat Bay and Little Egg Harbor Bay to predict how long water will stay at different locations. “They found that as you get further from the inlet, it could take a month or more for water to circle through and exit to the ocean,” Pfeiffer-Herbert said.

Stockton is leading the field component of the project and collaborating with researchers at Rutgers University and Oregon State University to model realistic predictions of our local bays and idealized predictions with what-if scenarios in a generic bay.

The research team captured views from the field in the gallery below.

LBI Inlet Study

LBI Inlet Study

LBI Inlet Study

LBI Inlet Study