Reaching 40 - Website Archive

Welcome

While the content reflects an earlier period in Stockton's history, it provides valuable insight into the university’s growth and evolution. We invite you to explore these pages as a snapshot of our foundations and the continued progress that has followed.

Reaching 40 book chapters:

This archived website offers a preview of each chapter of the Reaching 40 book, beginning with The Stockton Idea. Each chapter preview includes photos from Stockton’s history, alongside a complete list of the essays featured within each section.

Reaching 40 : The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey

c2011 — ISBN: 978-0615489407

The Stockton Idea

Stockton proposed to make available to state college students at state college prices the kind of interdisciplinary and individualized liberal arts instruction initially developed in America for the children of the ruling elite and, in the contemporary world, usually reserved for students at the most exclusive and expensive private liberal arts colleges.

Inside The Stockton Idea:

Elite Education for State College Students

William T. Daly

In other words, what was arguably the best and most expensive undergraduate education in the country was to be delivered to the students who most needed it but who also could least afford it and (as a number of early critics argued) might also be the least prepared for it and the least interested in it. State college students were known to range from very well-prepared to very poorly prepared, but the average level of academic preparation was likely to be a good deal lower than that which could be assured by rigorous admissions standards for entering students at exclusive liberal arts colleges. And the economic situation of many state college students and their parents was likely to place them generally in the career-oriented camp. They were unlikely to be attracted to a college that preached the civilizing impact of liberal arts education unless it could be demonstrated that such an education would also contribute directly to career success and economic gain.

This attempt to combine what was in the early days virtually open admission access with high-powered education once admitted, to combine working-class career education with upper-class liberal arts education, was exquisite 1960s stuff—noble to the core in concept but also audacious and likely to prove difficult in the implementation phase—as we and a few other like-minded colleges of the Sixties were soon to discover.

It was my distinct impression, as the first-year faculty assembled in fall 1971, that those of us who had packed our bags and come running to serve the Stockton Idea were attracted both by the nobility of Stockton's educational goals and by the near impossibility of achieving them. We were overwhelmingly young. It was the end of the Sixties. And we could still hear the ringing words of John Kennedy, speaking of the quest to put men on the moon: "We choose to do these things, not because they are easy but because they are ha-a-a-ard" (New England for "hard").

We arrived at the College (temporarily housed in the collapsing boardwalk Mayflower Hotel) to discover that the administrative planning team , which had spent the previous year constructing an initial plan for Stockton, had anticipated many of the difficulties associated with Stockton's declared and very ambitious mission and had built distinctive structures into the College plan designed to give us a fighting chance of actually making elite liberal arts education work for a career-oriented state college student body. All of those distinctive structures were compelled by hard realities to evolve during the first ten years of the College. But they are all still here and are all still central to what makes Stockton different, and arguably better, than most other undergraduate institutions. I have focused on four of these pillars of the Stockton Idea.

- The General Studies program and the traditional degree programs

- The Skills program

- The Preceptorial Advising program

- College-wide faculty involvement in all of the above

What follows in this book is a summary of the early thinking (as I understood it) behind each of these structures, of their evolution during the first ten years of the College, and (much more briefly) of their current status both at Stockton and in contemporary American higher education—as this lovely little college approaches its fortieth birthday.

Getting Started

In this section of the volume focuses on the earliest days of the College, from the planning undertaken by President Bjork, the board members, and the newly appointed deans, to the College's first classes at the Mayflower Hotel in Atlantic City.

Inside Getting Started:

What Have I Done?—Elizabeth Alton

Ken Tompkins

Choosing a Solution—David Taylor

Ken Tompkins

No Mere Substitute—Magda Leuchter

Ken Tompkins

Shakespeare Had it Wrong

Ken Tompkins and Rob Gregg

Breaking Eggs—Richard Bjork

Rob Gregg

Children of the Sixties

Daniel N. Moury

In a Heart Beat

Ken Tompkins

Observations

Richard Gajewski

Stockton Campus Planning, 1969-1974

Richard N. Schwartz

Different from the Beginning—NAMS

Daniel N. Moury

Why Go East?

Richard E. Pesqueira

Policing the Academy

James A. Williams

We begin with three different views of the early years. Based upon Elizabeth Alton's autobiography, and two interviews undertaken with David Taylor and Magda Leuchter, Ken Tompkins provides insights into what they believed they were endeavoring to accomplish, and how they perceived the College that they helped to found.

What name the new institution would adopt was a very important issue, as for many at the time it seemed to signify what kind of college it would become. Would it be a local college with locally recruited students, or would it reach for state and regional influence? We endeavor to highlight the conflicts revolving around the name selection, show what alternatives were offered, bring into question several of the narratives associated with the naming, and consider briefly some of the reasons that the name has not always been considered a blessing.

The next essays provide insight into what several of the administrators at Stockton were doing and what they accomplished. Rob Gregg provides a glimpse into the mindset of the founding president, Richard Bjork, about whom so many have had strong feelings. Gregg finds much to praise about what Bjork did, and certainly finds no lack of vision in this activist president, but notes that many of his problems were those of his own making—in his belief that to be good he needed to be unpopular. Ken Tompkins then describes all the early deans who worked alongside him when the doors of the college opened, and Dan Moury gives an intimate view of what it was like to be a new dean at Stockton.

The essays that follow then drill a bit deeper into the Stockton foundation, revealing what was established at other levels. Richard Gajewski describes his experiences as the founding Vice President of Administration and Finance, responsible for overseeing the securing of land, budgets, and even undertaking some precepting. Richard Schwartz provides a very detailed and informative piece about what was going on behind the scenes in the planning and the building of the Pomona campus, showing what a remarkable feat of engineering and construction the main campus was, and why it would become such an important asset for the college over the years. Dan Moury follows with an in-depth view of the earliest days in the Division of Natural Science and Mathematics, giving a clear sense of why it was that that division (now school) developed such a strong sense of community and identity.

Richard Pesqueira provides a strong sense of the idealism affecting many like himself who arrived at the college. He had been comfortably established at a college in California, only to feel the urge to contribute to this experiment in southern New Jersey. He came east to take charge of Student Affairs at Stockton, which he found to be very rewarding, though sometimes difficult owing to Bjork's position on the role of Student Affairs at his college. James Williams also had a difficult job in endeavoring to establish a police force at the college. As his essay shows, he needed to provide security in such a way that he would not alienate students and faculty, who were very much influenced by 1960s culture, while also appearing to be professional to the other forces in the region. His work was not made easier by the fact that he was the only African American chief in the region, and he needed to work hard to earn the respect of some insensitive colleagues who frequently referred to him as "the boy out there at Stockton."

The section ends with two pieces about the Mayflower period. Joe Tosh provides the perspective of a student in those heady days, while Lew Steiner focuses on the "sinking" of the Mayflower. Lew was the photographer for the Argo, and when the college moved to the main campus he fabricated a picture that made it seem as if the hotel was sinking into the ocean. The Mayflower had been a temporary vessel for the college, so this apparent demise seemed only fitting.

Throughout the section one gets a clear sense that hope was in the air. For all of those present at the founding, Stockton was supposed to be a different college. Indeed it was intended to be unlike all the colleges that the founders had experienced in their own educations. But could it fulfill this promise? Could it reach for the highest ideals and meet the expectations of all those who arrived in Pomona to become a part of the Stockton experiment.

Settling In

After the first heady months of its existence, the College began to settle down to life as another state college of New Jersey. Some of the idealism remained, and new ideas continued to be brought forward, but a spirit of conflict seemed to predominate.

Inside Settling In:

"Stockton Changed Me, More than I Changed Stockton"—Peter Mitchell

Rob Gregg

Building an Environment for Excellence—Vera King Farris

Harvey Kesselman

Shared Governance?

Robert Helsabeck

The Union Made Us Strong

John W. Searight

Life Sports

Joseph Rubenstein

The Mighty Burner — G. Larry James

Rob Gregg

When Lower K-Wing Rocked the World

Melaku Lakew and Patricia Reid-Merritt

Providing Funds

Jeanne Sparacino Lewis

Stockton Campus Planning, 1969-1974

Richard N. Schwartz

Reflections

Nancy S. Messina

Nurturing Community

Elaine Ingulli

Voices and Experiences that Echo Across Time

Franklin Ojeda Smith

In Good Faith

Nancy W. Hicks

Stockton's Impact on the Community

Israel Posner

The Organizational Paradox

William C. Lubenow

Questions of governance came to the fore, because these were very much contested. Was the college to be led by a powerful executive, in the form of a president and his or her Board of Trustees? Or would a system of shared governance gain hold? And, if it was to be a case of shared governance, what was the power of each constituent element—Faculty Assembly, unions, student body, administration—to be?

In the first two pieces, we are immediately introduced to two presidents whose tenures at Stockton make an interesting contrast. Rob Gregg shows that Peter Mitchell was a man who, to some extent, was a victim of the backlash that occurred against Richard Bjork. He had been chosen to be more open and democratic, but this, in part, led to his downfall, as he had no clear power base upon which to rely. Harvey Kesselman provides a nuanced view of Vera King Farris, whose tenure saw the College grow significantly in a number of ways, but who, like the first president, was not willing to brook much opposition. As a result, feelings were strong about her: many faculty ended up seeing themselves as her adversaries, while there were many others who remained fiercely loyal to her. However, all members of the college community had to respect what she accomplished.

The next two essays view the college from the faculty's perspective. Bob Helsabeck describes in great detail the story of governance at the college, showing how it has changed and describing what he feels it ought to look like. John Searight provides an excellent tribute to the Stockton Federation of Teachers, revealing the many ways in which, by fighting for the rights of its members, it was able to contribute, along with its sister unions, to creating a fair and decent work environment for all Stockton's employees.

Next, we turn to the brief attempt to establish Life Sports at Stockton. Joe Rubenstein (who has since gone on to be the faculty's liaison to the NCAA Division III teams, and who was a great cheerleader for the men's soccer team that won the National Championship in 2001) describes how innovative Stockton tried to be and what his colleague Marty Miller brought to the college community. Based upon the college obituaries for Larry James, Gregg then pays tribute to the importance of "The Mighty Burner," both to the growth of Athletics and to Stockton as a whole.

The next essays provide different perspectives of the college. Jeanne Lewis describes being a young administrator endeavoring to help students afford to come to Stockton, a job that has become increasingly difficult over the years. Nancy Messina reflects on what it was like rising through the ranks of Arts and Humanities, while also pursuing degrees, and witnessing the changes that have occurred all around the college.

The three essays that follow provide different views of the college in its earlier years. Melaku Lakew and Pat Reid-Merritt describe the faculty culture of lower K-wing, the residents of which crossed disciplinary boundaries and worked well together both intellectually and socially. It is a different way of looking at Stockton—and one that continues to have significance as we contemplate moving offices so that people of like disciplines live together—to see it from the perspective of the offices and their almost happenstance arrangement. Clearly, many liked this layout, and, quite possibly, each wing would have had its own story to tell. This is then reaffirmed in Elaine Ingulli's description of her first days at the college, describing how this kind of arrangement led her from her position within Business Studies into interdisciplinary teaching, most notably in Women's Studies. In the third of these essays, Franklin Smith touches on the experiences of being the longest serving African American faculty member at Stockton and the difficulties he faced pushing the college community to recognize its limitations in the area of race.

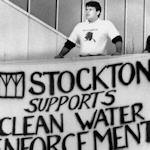

The next two essays reveal the College's endeavors to align itself, politically and economically, with the world beyond its gates. Nancy Hicks describes how she has endeavored in her position overseeing affirmative action and issues of diversity and equity at the College to keep Stockton in alignment with changing policies in the United States with regard to hiring and equal opportunity. Izzy Posner delineates what the College was endeavoring to do in the surrounding community and what its overall impact was. While the College had difficulties in this area at the beginning, he shows that early on it was committed to helping to transform the region.

Finally, Bill Lubenow, himself a Mayflower faculty member, provides an alternate view of the early years, that echoes, somewhat, the early questioning of the Stockton experiment that Alan Lacy in the Philosophy program had published in the Chronicle of Higher Education in 1974. Stockton has always provided space for difference, and there has never been a single way to look at what we are doing. Lubenow's vision certainly differs from many of those among the faculty who taught at the college in the early years.

So, while tensions flared up on numerous occasions, differences of opinion would be many, and a strike would be fought and won by the Stockton Federation of Teachers, the college would continue to grow, both in size and reputation. Perhaps more importantly for the long-term health of the institution, a feeling of camaraderie and solidarity would grow within Stockton's community that would sometimes smooth over the fractiousness.

The Primacy of Teaching

The focus of this chapter is the "primacy" of teaching. All educational institutions teach. The question, however, is whether teaching is the primary activity of the institution.

Inside Primacy of Teaching:

What Then Of a Legacy?

Joseph L. Walsh

Designing the Self—Creating General Studies at Stockton

Ken Tompkins

Joyous Serendipity

G. Jan Colijin

The Tsardeana of the Stockdons—Ingie Lafleur

Penelope Dugan

Life Sports

Joseph Rubenstein

Not Left Behind

Gordon William Sensiba

Dancing in Chains

Leonard Solo

The Origins of Teacher Education

Ronald J. Moss

A Brief History of NAMS

Roger Wood

A History of the Psychology Program

David Lester

The focus of this chapter is the "primacy" of teaching. All educational institutions teach. The question, however, is whether teaching is the primary activity of the institution. The founding deans and the first Vice President of Academic Affairs came from large research institutions where teaching was, much of the time, left to graduate students and adjuncts. Following Wes Tilley's insistence, research became a clear second-rate activity for faculty at Stockton, and teaching was the heart of all we did.

In a document dated August 1970, Wes Tilley—the Vice President of Academic Affairs of the yet to be built college—described the desiderata for recruitment of faculty. Two—the first two—of the list of seven are about teaching. Tilley writes:

(1) Our first consideration must be pedagogical excellence. This would be a simple requirement if it were not so easy to confuse with popularity.

(2) It is essential that the candidate show an interest in teaching the kinds of students we shall probably have at Stockton.

Not only was teaching the center of what we did, but Tilley further argued for a special kind of teaching: Socratic and interdisciplinary. At the heart of teaching were questions, and the answers to those questions were comprised of facts from a wide range of traditional disciplines. One way to see this working was in the multiple program memberships of most of the first faculty. Alan Lacy, Associate Professor of Philosophy, for instance, was a member of the Philosophy Program, the Environmental Studies Program, the Methods of Inquiry Program, and the Urban Studies Program. Each of these disciplines could be brought to bear on the others.

This heady mixture provides the context for the essays in this chapter.

Tilley's central postulations were not about the traditional disciplines on the whole; they focused almost exclusively on General Studies. These courses were to start with questions, they were to mix disciplines, and they were to have the most powerful and creative teaching. If we hired faculty who would tirelessly implement General Studies, the disciplinary teaching they did would, perforce, be exemplary.

Thus, the emphasis on the philosophical underpinnings of General Studies in essays by Joe Walsh and, then, by two Deans of General Studies: Ken Tompkins and Jan Colijn. Penny Dugan's reminiscences of a third dean, Ingie La Fleur, also emphasize the philosophy and feelings of possibility General Studies embodied in its early incarnations. Walsh analyses a seventy-five-page document by Tilley (1973), in which Tilley examines the state of General Studies and finds it wanting. Tilley's conclusion was that neither faculty nor students understood General Studies and, therefore, would not adhere to his original vision.

Colijn and Tompkins describe the state of the General Studies curriculum during their tenure; Dugan also describes it under La Fleur. All three authors discuss the ways that the collection of General Studies courses changed in the face of institutional change while the faculty generally tried to live up to the original ideas. Indeed, balancing change and original vision or intentions is a tension throughout this volume.

The pedagogy of questioning was at the heart of Bill Sensiba's teaching as he suggests in his essay. Bill was well-known for identifying with students' issues, for connecting with their lives, and for challenging them to change themselves and, ultimately, to strive to change the world. Thus he organized protest trips to Washington, protested nuclear power plants and took students to Guatamala to harvest coffee. What he understood was that questioning, though central to teaching inside the classroom, must be lived outside of the classroom. His essay reveals his struggles to confront his students, peers, and community with this central truth.

Originally, Stockton was not going to train teachers. The then-Chancellor of Higher Education in New Jersey was on record as not wanting the two new colleges to become teacher-training institutions. But local demand was so strong for the college to provide teacher training that it was added in 1970.

It was widely understood that Stockton was unlikely to train teachers in traditional ways—or for traditional employment. Therefore, the early Teacher Development Program (TDEV) was created to place teachers in alternative jobs—in alternative schools, homes for the elderly, prisons, and other forgotten environments. Leonard Solo reviews the problems he had with Stockton faculty and administration and, more significantly, with local public school leaders. As it turns out, Solo was unable to gain the confidence of the state to certify that Stockton's model was viable for training teachers. Ronald Moss reviews the process of reconstructing the curriculum so that the state would approve.

Finally, we selected two disciplines—psychology and literature—to examine how actual programs created curricula, offered classes, built labs, hired faculty, and still managed to balance the dream with the actuality of building a college. Both authors—Lester and Wood—are First Cohort faculty members so their history is, in many ways, the history of their individual programs and of the College.

Looking backwards, the tectonic fault lines are clear. It is easy to see where we succeeded and where we failed. It is easy to see which of our original ideas would work and which wouldn't. It is also clear that for forty years, there has been a tension between the dream and the actuality. Much of that dream was valid, significant, and truly unique. That is what this volume asserts is critical to understand and preserve.

Recent Trends in Teaching

In a sense, teaching in the very earliest years of the College was "pure" in that there were no assessment tools, no faculty training, no Writing Center, no minors, no graduate studies, and no infrastructure.

Inside Recent Trends in Teaching:

Cheerleader or Dreamer?—Stockton's Teaching Excellence

Alan F. Arcuri

Assessment—Good Teaching Practice

Sonia V. Gonsalves

The Quantitative Reasoning Across the Disciplines (QUAD) Program

Frank A. Cerreto

Planting a Program with Deep Roots and Good Growth—Writing at Stockton

Penelope Dugan

Born (and Reborn) Within the Currents of Academia: The Shifting Literature Curriculum

Thomas Kinsella

Changing Lives—The Interdisciplinary Minors

Linda Williamson Nelson

The Information Age at Stockton

James McCarthy

advising @ stockton.edu

Peter L. Hagen

The Most Transfer-friendly Institution in the State

Thomas J. Grites

As Mark Hopkins said, "The best school is a log with a teacher on one end and a student on the other." That is essentially what Stockton was early on.

The support system that the College now proudly offers its teachers took years to produce and the elements of that support system have been responses to wider, cultural changes in higher education.

The writers in this section generally embrace this support though Alan Arcuri regrets what he sees as a shift from student-centered teaching to research interests and teaching that doesn't always place the student firmly "on the other end of the log."

Assessment is, of course, a fact of a teaching life these days, and Sonia Gonsalves reviews Stockton's efforts to create acceptable tools for assessing learning while providing support for new teachers with workshops and semester-long training.

Penny Dugan and Frank Cerreto focus on writing and quantitative reasoning training. Stockton was one of the earliest colleges to offer Writing Across the Curriculum and, later, Quantitative Reasoning Across the Disciplines. We can rightfully be proud of these efforts, especially because early models for both skills were minimal though faculty-wide.

Dugan and Tom Kinsella delineate the role of the disciplinary program at the college. (There are other reviews of programmatic history elsewhere in the volume.) Both see their programs as constantly changing, challenged by technology, struggling to acquire resources, and proud of their program's efforts and achievements up to the present time. The same can easily be said about the various interdisciplinary minors at the College; Linda Nelson surveys their growth and impact. The Women's Studies minor, for instance, is one of the largest and most active in the lives of women at the College.

There was, of course, almost no technological infrastructure at the start of the College. Stockton was a "node" in a larger, state network as Jim McCarthy notes in his review of the phenomenal growth of technology on campus.

Perhaps the most obvious impact Stockton has had on national higher education is with the concept of "advising as teaching."

Making each faculty a preceptor and defining that role as teaching has, in the years since 1971 when Stockton began the practice, become a national mantra for advising. Peter Hagen, who has been at the center of defining advising this way, thoroughly discusses this history and the effect we have had on the whole nation.

Finally, in the earliest days, transfer students were half of the student population, and we had arranged with all of the state's community colleges to admit anyone they sent us. The result of this agreement has, over the forty-year history, continued to provide Stockton with a generous supply of capable transfer students. As Tom Grites points out, we have been and continue to be the "most transfer-friendly institution in the state."

The Spaces We Occupy

It is wonderfully ironic that the word "sustainability" first appeared in a printed text in 1972—a year after the College's founding.

Inside Spaces We Occupy:

Environmental Studies at Stockton

Claude Epstein

Sustainability at Stockton

Tait Chirenje and Patrick Hossay

The Natural Environment

Jamie Cromartie

The Oxford English Dictionary has this quote from the original work:

1972T. Sowell Say's Law iii. 100. An increase beyond limits of sustainability existing at any given time would lead only to reduced earnings and subsequent contraction of the quantity supplied.

1980 Jrnl. Royal Soc. Arts July 495/2. Sustainability in the management of both individual wild species and ecosystems is critical to human welfare.

In this sense, Stockton's emphasis on the concept of sustainability and the word that describes it grew up together.

In a very real way, the Environmental Studies Program (ENVL) was the progenitor of sustainability here. It is doubtful that, without the ENVL faculty, the College would have been so prominently recognized for its efforts to preserve and continue its projects. From the very beginning—even before the land was purchased—it was supposed to be an institution centered on the environment and preserving it.

As Claude Epstein so clearly states, Environmental Studies hardly existed in 1971 as a separate discipline and while student interest in the courses was well-intentioned, student participation was more romantic than realistic. In addition, there was the credibility of the discipline as a concern in the surrounding communities. Even if students worked their way through the ENVL curriculum, there weren't any jobs for them to seek. Also, in the 1980s, the College itself set up personnel policies that worked against continuing an effective environmental program.

The ENVL program has, in spite of these setbacks, survived and has strongly advocated for rational and sustainable growth matched with preservation.

Tait Chirenje and Patrick Hossay write a long and comprehensive history of what "sustainability" means at the College, what has limited it, and what the future holds as the College tries to balance the forces pressuring it from all sides. They discuss four issues: (1) sustainability across the curriculum, (2) institutional structures, (3) energy use and conservation, and (4) energy generation and purchase. They also discuss solutions that have been or need to be adopted. They are honest in identifying the time when there has been little or no collaboration between the administration and the faculty.

Through a thorough discussion of what has worked, what hasn't, and why, the two authors still seem optimistic for the future of our efforts. Curricula are being designed to stress sustainability, students are graduating and finding employment, and our national reputation for these efforts is solid and held in much esteem. Their essay ends:

All of us understand that Stockton College must now commit itself to growing in a way that ensures a clear commitment toward environmental stewardship, energy efficiency, and addressing the great threat of climate change. We can set a new standard in green design, efficiency, and stewardship that could serve as a model for other public and private institutions; we can earn the title of New Jersey's Green College.

Jamie Cromartie's essay is less positive. His argument is based on his experiences when trying to protect the site's biodiversity and its water quality. These are, as he points out, serious issues for any complex located within the Pine Barrens. He suggests that the problems come not from lack of environmental expertise or from innovative plans for protection but, rather, from a lack of clear collaboration between the ENVL faculty and administrations from the beginning of the College to the present. Specifically, Cromartie objects to the lack of implementation of the 1971 Master Plan in three areas of concern: professional management of forested areas, innovative use of native plants, and, finally, planned runoff from College buildings (to avoid damage to Lake Fred).

These are warnings to all of us that this precious environment cannot be maintained without careful planning and an understanding that our need to develop and grow must be matched with our need to preserve what we have inherited. The lesson—an old one—is that we are but stewards and that, in some absolute sense, we do not own the spaces we occupy.

Promoting the Professions

Unlike the other divisions, the birth of the School of Professional Studies (previously called the Division of Professional Studies and originally called the Division of Management Sciences) was not easy.

Inside Promoting the Professions:

Professional Studies: Competing Perspectives

Marc Lowenstein

In Pursuit of Professions

Marilyn Vito

Health Science Education at Stockton

Nancy Taggart Davis

Embracing Graduate Education

Bess Kathrins

Growth and Change—Graduate Study

Deborah M. Figart

For the other divisions, the person hired as dean created a collection of programs), and hired faculty who fleshed the programs out with curricula.

Not so Management Sciences.

First, the original Vice President for Academic Affairs, Wes Tilley, didn't really like curricula that offered vocational courses. He knew that, eventually, the College would have to offer professional courses, but he insisted that they be taught by a faculty who gave allegiance to the liberal arts. The other deans pretty much concurred.

So, while the four deans of traditional liberal arts subjects were hired in the spring of 1970, the Dean of Management Sciences was not hired until the fall of 1970. That person was not part of the conceptual planning, not part of recruiting of the First Cohort of faculty, and not part of the community-building that was so central to the work of the original deans.

In addition, the first candidate for Dean of Management Sciences—shortly after the position was offered to him—developed an inoperable brain tumor. We were forced to do a second national search, thereby delaying the vital planning it takes to create a college division.

The candidate we did hire, John Rickert, seemed a right fit for what we had already created, but personal problems prevented him from full participation in the planning process. While he hired the first faculty and created the necessary structure, he was never effective.

The wider community—in contradistinction to the founding vice president and deans, who insisted on a liberal arts focus—wanted the College to offer wide vocational curricula. The Atlantic City hoteliers asked for students trained in hotel management, the FAA Technology Center requested engineers and safety technicians, and local school districts strongly urged us to produce quality teachers.

Some professional curricula were needed; it was a matter of what kind of faculty and what kind of courses would be offered by the Management Sciences division. These tectonic faults are at the center of Marc Lowenstein's excellent survey of the creation of Management Sciences. For Lowenstein, the two points of view are Vice President Tilley's and President Bjork's. Bjork insisted that Stockton was not a "liberal arts college" and that it would certainly have professional programs). John Rickert, for his part, argued that whatever curricula the division finally produced, they would be based solidly on the liberal arts. It should be clear that Rickert was securely in the vice president's camp—to no avail.

As the national academic culture changed, Bjork's perspective prevailed. Management Sciences became more specifically vocational, less influenced by the liberal arts, and, unfortunately, less connected to the other divisions at the College.

Nancy Davis' essay also outlines the struggle to produce a variety of Health Sciences programs at the College. Resistance came from students who didn't see the value of Biomedical Communications, or the president—Peter Mitchell—who saw the health sciences costing too much, or faculty asked to initiate programs with no experience in that discipline. Davis' long and solitary struggle is both a warning and a confirmation to faculty. It warns faculty that new programs can be designed on paper but take on a life of their own when fully created. It is a confirmation that one faculty member committed to a cause can succeed when nimble and clever and, most of all, persistent.

It took years before support for graduate programs developed, as Bess Kathrins suggests, though from the very earliest days they were anticipated. Deb Figart thoroughly reviews the history and process of creating graduate programs; there are thirteen at the College as of 2011. The earliest was the Business Program—now an MBA—started in 1997. In 1997, 165 students had enrolled in two graduate programs; in 2009 enrollment had grown to 746 students.

The growth of Professional Studies at Stockton reflects that same growth nationally. Students have become very practical expecting that their courses lead to employment. This is understandable given a present unemployment rate of nine percent. But one wonders what will support these same students when, in the middle of their lives, they consider retirement or second careers. Will they not be limited given the narrowness of their early training? Somehow we need to seek a middle ground in the competing ideas of the liberal arts on one hand and professional studies on the other. Given its innovative history, the College needs to bridge this gap more effectively.

Looking Forward

The final substantive section of this volume focuses on the recent past at Stockton with an eye to how we are moving forward.

Inside Looking Forward:

Toward the Environmentally Responsible Learning Community

Rob Gregg

20/20 Vision

Claudeen Keenan

Changes at the Turn of the Century

Rob Gregg and Claudine Keenan (with assistance from David Carr and Marc Lowenstein)

A Tribute to Stephen Dunn

BJ Ward

Not Taken for Granted

Beth Olsen

Stockton's Regional Economic Contribution

Oliver Cooke

Impacting the Region

Harvey Kesselman and Patricia Weeks

Enhancing New Jersey's Public Child Welfare System

Diane S. Falk

Tales from an Argonaut

Emily Heerema

Stockton is now positioned in a way that it can become a major force for educational advancement in the region. In part this is due to sound fiscal management over the last ten years, which has allowed the college to invest in new buildings, as well as do so without falling dangerously into debt as other colleges have done. The college has come through the last few lean years of the economic downturn and declining state support, better off than many other public and private institutions in the mid-Atlantic region. In part, though, it is also because of the college's heritage, drawing on the innovations of the past and being willing to adapt to the changing educational landscape. Here the Stockton Idea has been of importance in helping the College retain its critical and creative edge, while remaining committed to benefitting the surrounding communities by its presence in southern New Jersey.

In the first essay, Rob Gregg describes the significant contributions Stockton's fourth president, Herman J. Saatkamp, Jr., has made to the College. This is then complemented by two pieces that focus on the Stockton strategic plan, the 20/20 Vision and, the changes that have occurred since the mid-1990s. Stockton began to undergo a major transformation from being a college that was divided between an administration that tended to be very hierarchical in its approach and a faculty that was quite belligerent in its opposition to administrative initiatives, to being one that is very much more harmonious in the relations among all the various constituencies. The unions remain powerful and respected, the faculty assembly has been replaced by a more effective governmental body (the Faculty Senate), and, while conflict has not evaporated entirely, there has been a greater sense of cooperation with the administration.

In 2001, Stockton witnessed one of its faculty members receiving a Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Stephen Dunn had been well respected for many years and had published a great many books of poetry – some of the best known works being "Between Angels," "Landscape at the End of the Century," "Loosestrife," "Everything Else in the World," and his most recent, "Here and Now." But the Pulitzer Prize was certainly an honor of a greater magnitude than he or any other Stockton faculty member had ever received. Dunn was awarded the honor for his work—"Different Hours"—from which "The Metaphysicians of South Jersey", printed below, comes. This is accompanied by two other Southern New Jersey poems, "At the Smithville Methodist Church," and "Landscape at the Turn of the Century." Stephen also has a great reputation as an inspirational teacher and a taskmaster who is able to provoke the will to search for great writing in his students. Poet BJ Ward, who graduated from Stockton in 1989, highlights this element of Stephen's accomplished career at Stockton.

Much of the published work produced by Stockton's faculty has been supported by college funding. Beth Olsen's discussion of grant seeking highlights an important element of Stockton's future, namely the ability of the faculty to secure funding for their innovative research and creative endeavors. Such funding will help the college build on its reputation both regionally and nationally.

In the next part we return to the contributions Stockton has made to the community. The first of these essays draws on the expertise of Economics professor, Oliver Cooke, who outlines the College's economic contribution to the region – which has been very significant in the past and looks like it will only grow in the future with the acquisition of the Seaview Hotel, a new educational center in Hammonton, and other projects throughout Atlantic County and southern New Jersey. Harvey Kesselman and Patricia Weeks then provide a brief history of the Southern Regional Institute & Educational Technology Training Center, which has had a great impact on all area public schools, through the services and training it has provided to area teachers. Diane Falk then discusses the development of the Baccalaureate Child Welfare Education Program, an innovative venture that has dramatically enhanced the state's Public Child Welfare System. Once again, Stockton has made contributions to the area through the arts. In addition to the on-going efforts of the Performing Arts Center, led by Michael Cool, Beverly Vaughn and Henry van Kuiken, with more than 30 years of service to the college each, have been electrifying audiences with their dance and choral concerts that have been generated in the classroom and have been performed to area audiences. Beverly Vaughn, in particular, has been one of the premier ambassadors for the college, increasing awareness of Stockton among residents of all the surrounding communities.

The last word goes to a recent editor of the Argo, Emily Heerema, describing her work as a recent editor of the student newspaper, which has been appearing continuously since the earliest days of the college (the first issue being published on October 29, 1971). Through her service as editor, Heerema helped revive interest in the student newspaper, making it once again an important voice for students.

Stockton 50th

This site delves deeper into Stockton’s journey and growth, featuring additional milestones and a richer collection of images.

Additional content:

Blogging 40: Reflections on Telling Stockton's Stories Paperback

Contributors:

Editors

Ken Tompkins and Rob Gregg

Copy Editor

Lisa Honaker

Designer & Cover Photo

Margot Alten

Endpaper Art

David Ahlsted, 'Seasons'

Web Design

Daniel Gambert

© 2012 Stockton University

David Ahlsted

Margot Alten

Alan F. Arcuri

David Carr

Frank A. Cerreto

Tait Chirenje

G. Jan Colijn

Oliver Cooke

Arnaldo Cordero Román

Diane S. Falk

Deborah M. Figart

Richard Gajewksi

Sonia V. Gonsalves

Rob Gregg

Tom Grites

Peter Hagen

Emily Heerema

Jeanne Sparacino

Lewis David Lester

Marc Lowenstein

William Lubenow

James McCarthy

Michael McGarvey

Nancy Messina

Ronald J. Moss

Daniel N. Moury

John W. Searight

William Sensiba

Franklin Ojeda Smith

Len Solo

Lew Steiner

Joel Sternfeld

Ken Tompkins

Joseph A. Tosh

Hannah Ueno

Jamie Cromartie

Bill Daly Gordon

Davies Nancy

Taggart Davis

Penelope Dugan

Stephen Dunn

Claude Epstein Bob

Helsabeck Nancy

W. Hicks

Patrick Hossay

Elaine Ingulli

Bess Kathrins

Claudine Keenan

Harvey Kesselman

Tom Kinsella

Melaku Lakew

Joyce Lawrence

Linda Williamson Nelson

Beth Olsen

Richard E. Pesqueira

Israel Posner

Patricia Reid-Merritt

Joe Rubenstein

Richard N. Schwartz

Marilyn E. Vito

Joseph L. Walsh

BJ Ward

Patricia Weeks

Wendel White

James A. Williams

Roger Wood