Fall 2020 Issue

In the early spring of 1998, curiosity led biology alumnus Dr. Rodger Gwiazdowski ’00 into the wooded area near the Pomona Road entrance, now known as North Lot. With hatchet in hand, Gwiazdowski rummaged through the woods in search of fallen dead trees which are known habitats for insects.

As he hacked open a decaying log, amongst the dark withered foliage, a bright emerald-green beetle emerged. It caught his eye. It was a Six Spotted Tiger Beetle. Although this is common for the area “I never knew they existed, and it was one of those moments where I was astounded,” said Gwiazdowski.

Excited with his find, Gwiazdowski spoke with faculty mentor and preceptor, Dr. Rudy Ardnt, Professor of Biology [1974 – 2007], who guided him to study the six-legged arthropod. Ardnt advised if he was thinking of a career in systematics or conservation, to “pick an organism or a group that nobody knows anything about.” Gwiazdowski went on to explain that Ardnt, a herpetologist and ichthyologist, told him “everything you discover will be new; all your colleagues would be happy; and there would be plenty of funding sources available.”

Two years later, a recovery plan assignment in a Stockton Conservation Biology class started Gwiazdowski’s preservation efforts for the tiger beetle. [A recovery plan outlines the path and tasks required to restore and secure self-sustaining wild populations. It is a non-regulatory document that describes, justifies, and schedules the research and management actions necessary to support recovery of a species. – NOAA Fisheries]

“The assignment was to identify an endangered species within the state [New Jersey] and create a recovery plan for it,” said Gwiazdowski. Thinking about his conversations with Ardnt, he decided to focus his plan on the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle.

Familiar with captive rearing through his summer work at the Bronx Zoo and the New York Aquarium, he thought this may be a way to preserve the species.

“I knew conservation measures for tiger beetles had been tried, and the main problem is that populations are rare, and going extinct. I thought if we captive reared them, it may be a great recovery tool,” he said. [Captive rearing is the process of breeding animals in a controlled environment to research, or reintroduce species that are being threatened by human activities such as habitat loss, fragmentation, predation, over hunting or fishing, pollution, disease, and parasitism.]

Gwiazdowski sought out information on the previous studies on tiger beetles and wrote letters to researchers who had written scientific articles on the insect.

“They all wrote back and sent reprints,” Gwiazdowski said with excitement. One of the responses came from the utmost authority on tiger beetles, Dr. C. Barry Knisley. [Knisley has made his life’s work researching this group of insects since the early 1970s. This connection proved to be significant for Gwiazdowski, as Knisley later collaborated with him on recovery projects and has remained his mentor for 20 years.] Gwiazdowski credits this experience at Stockton to his current conservation work and research. “Life is uncertain, but for this I can draw a straight line between my experiences at Stockton to leading this conservation work.”, he happily expressed.

Recovery of the Tiger Beetles

In 2015, Gwiazdowski received pilot grant funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Recovery project to build infrastructure for a controlled lab expressly for rearing the Puritan Tiger Beetle.

“Here was an opportunity to start using this tool that I first thought about in the conservation class at Stockton,” he said.

Once found living on river banks along the Connecticut River in New England and Chesapeake Bay beaches in Maryland, Puritan Tiger Beetle now exists in only a few isolated populations – and they are going extinct. The success of this [ongoing] recovery project lead to four-year grant to recover another species, the Northeastern Beach tiger beetle, a species which used to live on ocean beaches throughout the northeast, by repatriating larvae from their remaining populations in Massachusetts, to Sandy Hook in New Jersey.

After WWII, our use of beaches obliterated them from their habitat.” said Gwiazdowski about human modifications to coastal environments. “For this species, the adult tiger beetles are only out during the months of July and August when beach use is high. Improvements for humans, such as raking beaches to clean them, jetties, groins, or riprap radically change the habitat and make it unfit for beetles.”

It is unclear the impact of the extinction of the beetles has had on the ecosystem.

“Few species eat tiger beetles, and they are the top predators at the trophic level in their food web. They are mostly generalist predators. If they’re not present, it suggests there are other connections that are broken or frayed,” he explained about habitats along the coast.Over the next three years the larvae will be relocated, a process called translocation, just before they pupate.

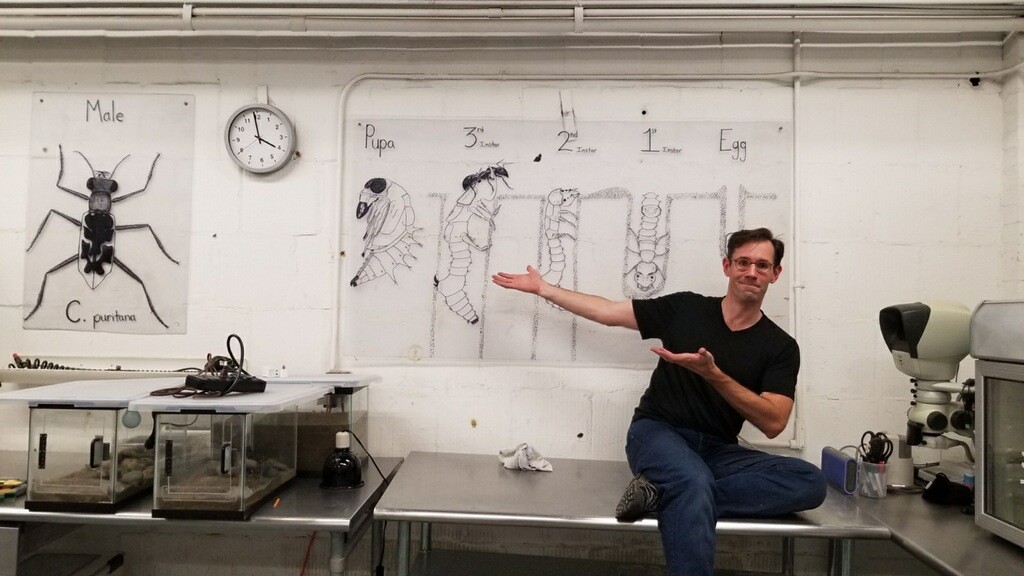

”The idea for the translocation is rooted in the life cycle. They [tiger beetles] take three years to develop from egg to adult. Like butterflies they have a complete life cycle with an egg, larvae, pupae, and adult, but unlike butterflies - these things are viscously predatory,” explained Gwiazdowski.

No need to worry about your next trip to the beach – tiger beetles are not harmful to people and will not bite. “They are super scary and vicious on a small scale,” laughed Gwiazdowski. He explains the reason for a larval translocation is, “We’ve found moving larvae just before they pupate has the best chance for establishing a population, because when they emerge as adults they stay at that site, and are ready to mate.”

The growth cycle takes time in the wild because the larvae live in a hole in the sand and eat only what they could catch as it goes by. In a controlled laboratory, Gwiazdowski and his team have seen other species of tiger beetles complete their life cycle within a few weeks to a couple months. This species pupates in late June to emerge as adults in early-to-mid July. They can be seen in their habitat as adults through August or early September if the weather is warm.

“The adult form of most tiger beetle species don’t have a long-life span. They live as adults for only several months and lay eggs that hatch into practically microscopic larvae,” explained Gwiazdowski.

The larvae have been translocated once this year, but the team intends to do two translocations in 2021. “Next year, we will move them in April and then May to stagger the timing,” said Gwiazdowski.

This isn’t the first time the tiger beetle larvae have been planted on Sandy Hook. In the late 1990’s, Gwiazdowski’s mentor, Dr. Barry Knisley, tried to repopulate the beetles using the larvae from the Chesapeake Bay region. An increase in the adult population was seen over a period of several years but did not take hold. It is thought that habitat dynamics were not ecologically compatible with the species of beetles.

“The Chesapeake Bay is very different than that of an ocean beach. The bay beach is narrow with low wave action, versus an ocean beach that has dynamic action. And we have some evidence that the larvae behave differently on the different beaches,” explained Gwiazdowski.

“Translocation is a crude, but effective way to test a hypothesis,” said Gwiazdowski. “Funding wasn’t available to do further studies on sediment or prey availability and other habitat metrics that would be connected with the tiger beetle’s life history. For the moment, we are going to see if this translocation project works just by moving the larvae.”

Tiger Beetle Larvae Collection and Transplanting

Gwiazdowski is optimistic about the recovery project. “Sandy Hook is the best available habitat we know of. Although beach use at Sandy Hook is highly contested because the coast guard occupies part of it, and the remaining public beaches are a patchwork mosaic of protected areas for plovers or other migratory birds. We’re hoping the beetles can find a home here. But even if the translocation fails, we didn’t fail to try,” he said.

This was the first year Gwiazdowski and his colleagues planted larvae in Sandy Hook. They will continue to relocate them through 2022, followed by a year of population monitoring.

Advice to Students

I graduated with a degree in Biology, a minor in Marine Science and wasn’t sure what to do next. Conservation biology seemed interesting, and important. So to get a sense of the field I read every editorial of every issue in the Journal of Conservation Biology to see where the field was going and what people were thinking. For natural science students who are not going into medical professions, it’s hard to predict what the world is going to look like next year.

Work with what interests you - where you can be an expert with something to give, and you will find your way.

Every team needs you to be an expert in something.

Mentorship matters. Find mentors with good character who ‘speak’ to you; people who encourage you to look at new things. My best mentors gave me freedom to explore, and courage to ask important questions. At Stockton, I was lucky that mentors like Rudy Arndt, (and many others I wish I could footnote here) - found me. Later, I cold-called and emailed questions to scientists whose papers inspired me. Almost all of them kindly replied and met with me and (amazingly!) some I still call for advice.

Failure is so important– yet not discussed enough. This article is about some successes, so I want to be clear that I fail. A lot. I still will, and it will still hurt. Though it seems if one’s persistent, their experience (i.e. your prior failures) helps form hypotheses with good (or at least insightful) outcomes – even when they fail. So, in closing - I do have magic advice - and it’s this: What if you ask more questions? On failure, one of my best questions comes from the late Rep. Elijah Cummings who said "When bad things happen to you, do not ask the question ‘Why did it happen to me?’ Ask the question, ‘Why did it happen for me?’”