Fall 2024 Issue

Image credit: Ed Boyden and Massachusetts Institute of Technology McGovern Institute

The story of biochemistry alumnus Noah H. Wenger ‘20 is one of resilience, self-discovery, and the unexpected twists that come with pursuing a career in science. He started his journey with aspirations of becoming a physician but ultimately uncovered a profound passion in research and neuro science.

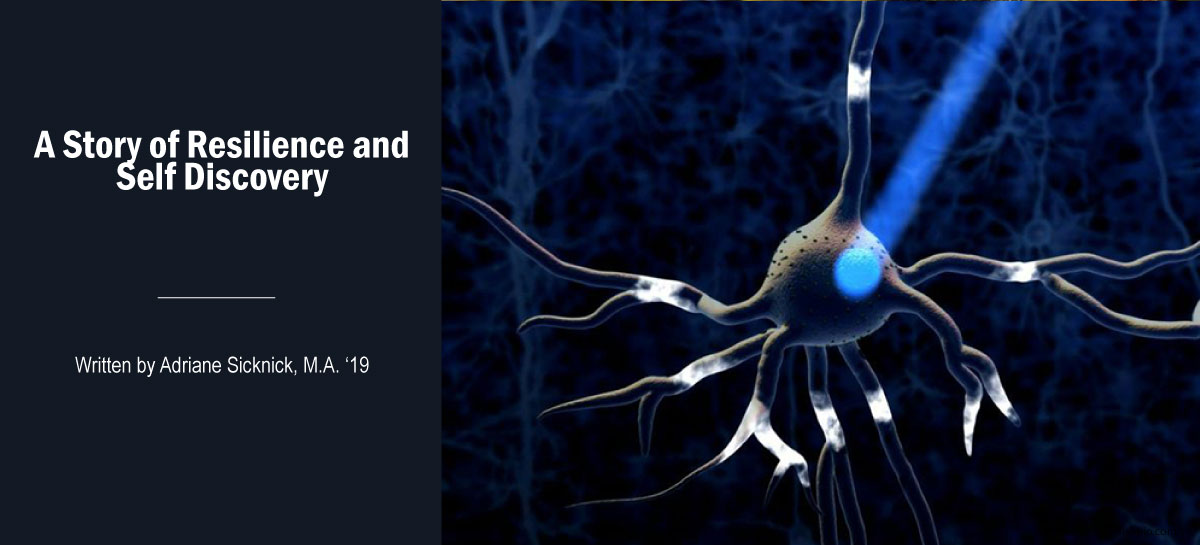

Noah Wenger '20 at Pavolian Conference 2024.

Photo credit: Noah Wenger.

With a firm belief that he would become a physician, Wenger took every necessary step to prepare, from attending an Allied Health program at his local vocational high school to completing medical prerequisite coursework and sitting for the MCATs multiple times. Despite his hard work and dedication, he failed to secure admission into a medical school. This could have been a significant setback for many, but for him, it was a pivotal moment to reevaluate not just his immediate goals but the path he had been following.

A Shift in Focus: Discovering Research

Wanting to build his med school application, Wenger enrolled in the biomedical science graduate program at Rowan University. During this time, he worked as a medical scribe in a cardiology office, gaining firsthand experience in the medical field's high-pressure environment. “I worked with some really great people, and I learned some amazing things, but it made me realize that I didn't want that lifestyle,” he said, reflecting on the demands of medical practice, especially in the post-COVID era. The experience also reignited his love for the sciences, particularly research.

He reflected on his undergraduate years working in Associate Professor of Biology Dr. Nathaniel Hartman's lab, where he first experienced the excitement of scientific inquiry. "I really felt like I was a part of the scientific process,” he fondly recalled. However, COVID disrupted research for many students, and he was unable to return to the lab during his master’s program as he anticipated. Focused on transitioning away from medicine, Wenger began job hunting in the biotechnology industry after graduating with his master’s in 2022. His perseverance paid off last September when he landed a position as a lab manager in a newly established behavioral neuroscience lab at Rowan University under Dr. Gunes Kutlu. “I’ve been in this role for a year now, and it’s been incredible,” he said.

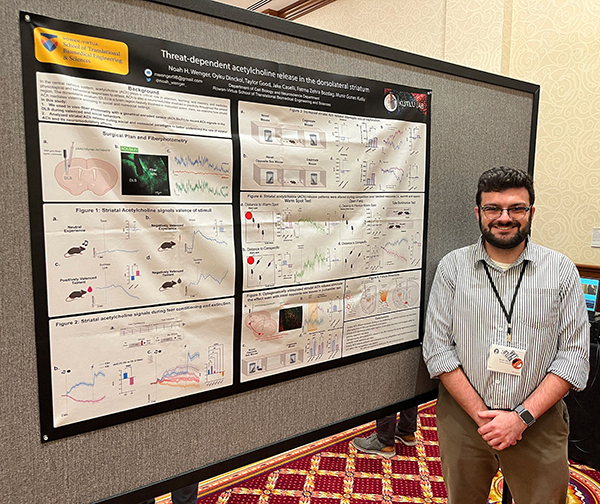

Photo credit: Noah Wenger.

In his current position, he wears many hats: overseeing day-to-day lab operations, conducting experiments, analyzing data, and managing logistics. The laboratory Wenger works in focuses on studying social and fear learning hierarchies in mice, particularly examining dorsolateral striatum (DLS) brain region and the neurotransmitter acetylcholine's role in these processes. Since viruses are good at carrying genetic information from one place to another, a genetic sensor (a fluorescent protein) is surgically injected into the DLS using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that will glow under a certain wavelength of light through an optic implant.

Single cell diagram.

Photo credit: Noah Wenger.

The research involves a series of experiments using an operant conditioning box to present various stimuli (neutral, positive, and negative) to the mice. The research team’s findings indicate that acetylcholine levels decrease during positive stimuli (like sucrose) and increase during negative stimuli (like quinine and mild foot shocks).

Subsequent experiments on fear conditioning show that acetylcholine levels rise in response to cues predicting shocks, whereas extinction trials reveal diminishing acetylcholine responses as the shocks are removed.

A significant aspect of the research is the use of miniature microscopes to visualize neuron activity in real time, identifying specific neurons that respond exclusively to negative stimuli. Future directions include the exploration of optogenetics to manipulate acetylcholine levels during behavioral experiments, aiming to deepen understanding of its role in learning and memory. The researchers plan to refine their approach to teaching mice that cues can predict safety, addressing confounding variables in their initial attempts.

Video explanation of optogenetics.

Overall, the lab is at the forefront of integrating advanced techniques to explore the neural mechanisms underlying learning and emotional responses in patients with diseases such as Alzheimer’s, anxiety, depression, and addiction.

Wenger explains, “The good thing about mammalian brains is they are conserved across species, so this can very easily be like the exact same pathway in humans, just on a much smaller scale… We don't have a particular disease model in mind, but the hope is that other scientists can use our research to develop medication to target a specific area in the brain.”

In a world where career aspirations can change and evolve, Wenger’s story is a reminder that sometimes, the most rewarding paths are the ones we never expected to take.

Single cell reaction

Warm spot experiment

GIF credit: Noah Wenger.

Advice for Students

Wenger is very close to his family and knew he didn’t want to be across the country for college. Stockton allowed him independence while staying on campus, but the comfort of being within driving distance of home.

In addition, he knew there weren’t any Ph.D. or Postdocs in his major at Stockton didn’t seem significant at the time he applied. However, when he started doing research, he realized that he had more responsibilities in the lab than other undergraduate students. “I was performing graduate-level work at the undergraduate level, and I think that really helped prepare me for the field I’m in now,” he explained.

Beyond the lab, Wenger’s college experience was enriched by involvement in student organizations, including Alpha Epsilon Pi, Chabad, Hillel, and the Chemistry Society, which fostered friendships and provided a vital social outlet. Reflecting on his journey, he emphasizes the importance of community in maintaining a balanced life during his intense academic years. “They helped me disconnect from schoolwork,” he shared, a reminder of the importance of camaraderie in the challenging world of science.

It’s going to be difficult. “Just know that everyone else is in the same boat and feels it is difficult, and that is okay. You're not going to know everything. You will learn it as you go. Take the time to put in the extra work after class. Go to the library and your professor’s office hours – I cannot stress that enough.”

It’s not all about the A’s. “In the professional world, they do not care about your GPA; they care more about your experience and your abilities. They’ll see what classes you took but that only adds to your experience that you have more than your GPA. Don’t be afraid to withdraw from the class you are not doing well in, causing other classes to suffer. One or two withdrawals on your transcript doesn’t matter in the professional world.”

You learn from failure. “You learn more from your failures than you do from your successes.”