Shells Go from Restaurant to Reef to Restore the Bay

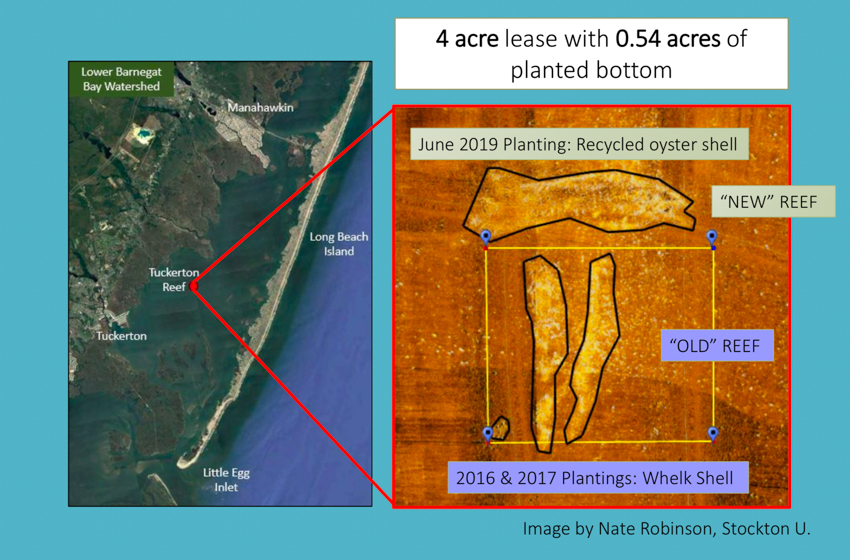

Galloway, N.J. - This June, a pile of recycled shells speckled with tiny growing oysters arrived at the Tuckerton Reef on a barge—enough to double the size of the two-acre reef that was first established in 2016.

The oyster is propelling the Barnegat Bay’s ecological resurgence with help from Stockton University scientists, an oyster farmer, restaurants, storytellers and the community who are coming together to continue the expansion of an experimental oyster reef.

The restoration project recycles shells from Ocean County restaurants into temporary nursery tanks where oyster seed is planted. Once the larval oysters are growing on the shells, they are returned to the bay to sustain habitat for more oysters that cleanse the water as filter feeders, provide shelter for marine life and dampen the erosional forces of wave activity.

As the reef transforms the marine ecosystem, oysters reveal their pearls of wisdom to scientists and shellfish farmers listening to the bay.

Underwater Planting

The 725-bushel load delivered in June was the largest planting to-date, bringing the total to 1,578 bushels on the reef.

From the stern of the R/V Petrel, Steve Evert, director of the Marine Field Station, guided Dale Parsons, a fifth-generation oyster farmer who operates Parsons Seafood on Green Street, and his crew to the reef location.

While floating above the oyster lease, the crew sprayed the shell pile into the bay using water pressure and a hose. The sun made a rainbow in the mist

as the oysters flew off the deck and sank into place.

While floating above the oyster lease, the crew sprayed the shell pile into the bay using water pressure and a hose. The sun made a rainbow in the mist

as the oysters flew off the deck and sank into place.

“Planting oysters looks a lot different than farming on land and comes with the challenge of working with an underwater plot. But technology helps us visualize,” explained Evert.

Just prior to this year’s planting, a sonar map of the oyster reef looked like the mathematical symbol Pi, with the 2016 and 2017 plantings making up the two legs and the 2019 planting stretching horizontally across the top.

Just as soil is a growing medium for plants, oyster shells are a substrate for oysters to multiply into a reef.

Oysters Tell Us How to Restore the Bay

Stockton researchers are listening to oysters to determine the best way to restore the bay. By gathering data at the experimental reef, they can make larger-scale predictions.

“This is a data driven process where we monitor and assess what we’re doing. We make changes if something is not working,” said Christine Thompson, assistant professor of Marine Science.

Thompson and her students monitor growth and survivorship of the oysters and sample marine life on and off the reef to assess habitat value for other species. See what lives on the reef here.

Anna Pfeiffer-Herbert, assistant professor of Marine Science, monitors water quality to determine how much water the oysters can filter.

“Think of an individual oyster as being a mini vacuum cleaner, so if you have a whole reef of oysters in an estuary that water will be cleared of suspended sediment, mud, extra phytoplankton—creating a better environment for humans and the species that live there,” explained Thompson.

Temperature, salinity, oxygen, turbidity, chlorophyll and pH affect oysters’ filtration potential.

A bright yellow buoy marking the lease houses sensors that record the water conditions every 10 minutes using optical and electrical properties.

Temperature, salinity and oxygen help to determine where and how well oysters can grow.

CAPTION: Elizabeth Zimmermann, field station assistant, films Christine Thompson for a Facebook live session during the reef planting. Watch the coverage on the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics Facebook page.

“Oysters in cold temperatures will slow down and stop pumping water. They will get faster and faster at filtering water up to a point, and when it gets too hot, like in August when the water can get up to 80 degrees, they’ll start to slow down because it’s stressful for them,” explained Pfeiffer-Herbert.

Turbidity or how cloudy the water is, measures how many particles are suspended in the water. “Oysters like to have something in the water to eat, but if there’s too much stuff and it’s not food, that will slow down their rate of taking material out of the water,” said Pfeiffer-Herbert.

While they are filtering water, oysters are eating chlorophyll, the green pigment in plants including microscopic plankton, so knowing how much chlorophyll is present indicates how much food is in the water.

Project History in a Half Shell

“Oysters have declined dramatically over the past 100 years. Historically there were millions of oysters in Barnegat Bay, and when you have a thriving oyster reef you will get the ecological benefits such as habitat for fish and invertebrates and the benefits of water quality from filtration,” said Thompson.

The reversal of the population plunge is a collaborative effort that blends science with generations of knowledge that comes from working on the water.

“For a long time, the general public assumed that there was nothing we could do to help the bay. The reef is a way to bring to light not only what can be done, but how the public can contribute through a shell recycling program. It's answering the questions of what and how,” Dale Parsons explained.

CAPTION: Dale Parsons and his crew load cages of shell onto a barge for the planting. Oyster seed is planted in tanks that hold cages of shell. After growing for about a month, the cages are lifted out and loaded onto a barge.

The Barnegat Bay Partnership provided initial funding and has continued supporting the reef, and the Jetty Rock Foundation came on board to support the effort and has helped communicate the recycling program to keep the reef growing.

A pilot project started with Old Causeway Steak and Oyster House in Manahawkin recycling their shells, and now 16 Ocean County restaurants are participating year-round.

Follow the Shell

“Shell recycling was a call to action from the Oyster Farmers film that debuted in 2017,” said Angela Andersen, a Stockton graduate, producer of the film and recycling coordinator for Long Beach Township.

Andersen and film director Corrine Ruff told the history of oysters in our region by following oyster farmers making a living on the bay.

"The abundance of shell that comes out of the restaurants is a direct result of the

oyster farms that exist from Mantoloking down to the Great Bay. We have over a dozen

oyster farms. That’s a dozen small businesses occurring right here in our backyard

producing volumes of product for restaurants," said Andersen.

With the new craze for boutique cocktail oysters came an opportunity. Andersen followed the shell to find out that recycling offers a chance to sustain the reef.

“Long Beach Township Major Mancini grew up on the bay on Long Beach Island and dedicated the resources of staff and vehicles, so we do the mechanical part of picking shell up from the restaurants and Jetty Rock Foundation is our marketing and design partner,” she explained.

Since 2017, 4,000 bushels of shell have been collected.

This year, recycling resumed on June 1, and Andersen is working on plans for people who are cooking at home to drop off their shells to a central location.

Andersen has also been working to open the Long Beach Township Marine Education Field Station that will soon offer a place for research, tours and events to connect people to science. For this summer, social distancing will allow outdoor and virtual programming.

“When you recycle a shell after you’ve eaten it, we are able to pick it up and bring it right back into the bay for restoration, filtration and the health of the community—economic growth, tourism growth and empowerment to the consumer who can play a role in marine science by closing the farm to table loop. There’s no better way to connect all of the science to the people,” said Andersen.

What's Next

A sample from the spat on shell that was planted is being counted by Christine Thompson for a final tally on the density of oysters planted.

When wild oysters spawn this summer, there is a chance they will settle onto the Tuckerton Reef like they have in past years.

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection has committed to funding next year's 2,000-bushel planting and to creating a second reef in 2022 further up the bay.

Dale Parsons hopes to create a carefully managed public access program "that would allow the public to take a bushel or two home outside of vibrio season and contribute directly to the reef," he explained.

To learn more about the Stockton Marine Field Station, visit their website and follow their Facebook page. For updates on the reef, follow @stocktonshellfishlab on Instagram.

Reported and photographed by Susan Allen

More photos on Flickr.