The Truth About Berline Stephens

By Ken Tompkins

The Story

In the summer of 1970 when I came to New Jersey to help start the College, I heard the following story told a few times but always with the same details:

When President Bjork took the position here of President, he brought with him from the Department of Higher Education in Trenton, a young African-American to be his executive secretary. She had only lived here a short time when, on a winter night, she was driving across the Margate causeway, hit an ice patch and her car flipped into a waterway. Both she and her infant son were killed.

What a sad story!

I had just arrived with my family – my wife and two infant children – for a challenging new position. Like she must have had, I had dreams of a new life here. Like her, we had no new friends and, like her, had commanding responsibilities both in the job and in our small family. The story stuck in my head for more than 40 years.

A year ago, memories of the young woman flashed into my mind and, thinking about her and her child, I was startled that I did not know her name. Assuming that I had forgotten that detail of the story, I contacted Carol Brown – the woman who became the President’s secretary, after the accident. I repeated the story and asked if I had those details correct (I did) and then asked her name. Carol didn’t remember.

Bjork had an assistant – Richard Chait – who still works at Harvard so I contacted him. He said I had the details of the incident correct but that he, too, did not remember her name.

Now, having worked on my genealogy, and my wife’s, for 40 years, being able to name an ancestor is critical. It is a sort of doorway into all of the other facts about a person’s life. For example, we recently were given about 340 photographs of people in my wife’s New England family. These were photos from just after the Civil War to 1900. Many had notes on the back that identified them. With names I could add them to her family tree and immediately they became ancestors like Frederick Thayer who graduated from Dartmouth in 1873, started a newspaper in Hanover, NH, was a reporter at the NY Times by 1875, entered a seminary in Bangor, ME, and in 1878 became the pastor of a church in Quincy, IL, dying at 33 years.

Without a name, there is no birth, no education, no family, no achievements and no death.

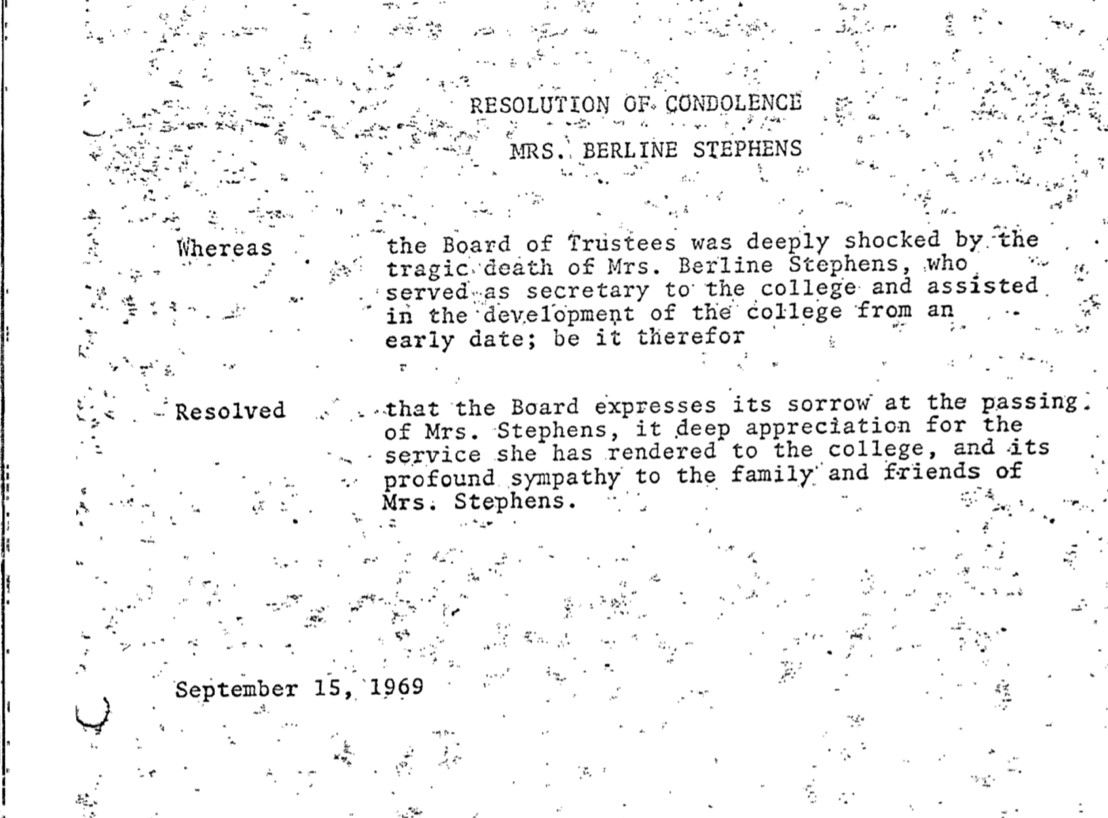

My search for the name of Bjork’s secretary started with a search in the records of the College Board of Trustees. That record goes from 1969 to the present. I asked Louise Tillstrom, the assistant in our Archives, to search for anything about her death. It seemed to me that the Board would have recognized her service with at least a note. Here is what she found:

Ah! Her name was Berline Stephens and the Resolution was written at the Board meeting on September 15, 1969. These two pieces of information – a name and a date – opened the door to her life and to the achievements of her family. It is a story well worth the telling.

Using these two facts, I began searching online newspaper collections. Immediately, I found her obituary in the Trenton Times.

The Facts:

The final resting place of Berline and her son, Gregory.

The final resting place of Berline and her son, Gregory.

- She and her son were killed on September 8th, 1969, driving into Atlantic City – not on the Margate causeway.

- It was not a winter night but, rather, a rainy night in early September.

- Her car was hit from behind and it was driven into construction and flipped into a part of Lakes bay. She did not slip on ice.

- Her son, Gregory, was not a baby but, instead, was a 17-year-old high school student.

- Other facts – her maiden name was Williams and she came from a large African-American family of 7 children.

- She and her son are buried in Trenton’s Greenwood Cemetery.

The Williams Family

One of the values of obituaries are the lists of named relatives. As well as finding the facts of Berline Stephens’ death, I also found the list of her brothers’ and sisters’ names:

Margaret Cane – I’ve not yet found any information about Margaret. She seems to have been the first child having been born in 1924.

Muriel Mitchell – I have not found any information about Muriel. I believe that all of the children were married but I haven’t found confirming evidence of it.

Thelma Williams – As far as I know Thelma is the only surviving member of the family. She received a Doctorate in Education from Trenton State (I assume that all of the family went to college at Trenton State), taught for years and, ultimately, became a member of the State Board of Education.

Ernest Williams – Ernest was born in 1934. He served in the military and in the Trenton Police. Eventually, he became the first African-American to serve as the Chief of Police in Trenton.

Leon Williams – Leon became a music manager for Trenton bands and was the owner of a popular restaurant.

Arnold Williams – Was in the Vietnam war rising to the rank of Lt. Col. in the Army.

Though thin on details, I’ve included members of the family to highlight their considerable accomplishments. They all went to school and, most likely, college. They all lived in serving professions.

Berline Williams (Mother of Berline Stephens)

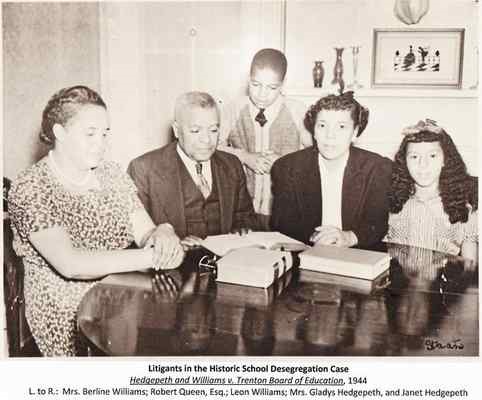

An old photo of Berline and her family.

An old photo of Berline and her family.

When the school year began in 1943, Leon, who was beginning Junior High, had to walk 2.5 miles to the Lincoln School while white students in the neighborhood attended the all-white Junior High No.2 which was a couple of blocks from the Williams’ home. Berline Williams and a neighbor named Gladys Hedgepeth decided to take their children – Leon and Janet – to the white Junior High No.2 school but were told “no”; that the school “was not built for Negroes.” Being righteously outraged, they were determined to do something about it.

There was actually an existing law that said:

…it is unlawful for boards of education to exclude children from any public school on the grounds that they are of the negro race.

Berline Williams and Gladys Hedgepeth went to the local NAACP chapter and secured the legal services of Robert Queen. The case against the Trenton Board of Education was on.

The decision, a year later, said that the Junior School No. 2 had “unlawfully discriminated” against the students.

In 1954, the Hedgepeth and Williams case was the only state anti-segregation precedent in the United States and, as such, was used by Thurgood Marshall in Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1991, the Trenton School Board changed the name of Junior School No. 2 to the Hedgepeth – Williams Middle School.

From little acorns mighty oaks.

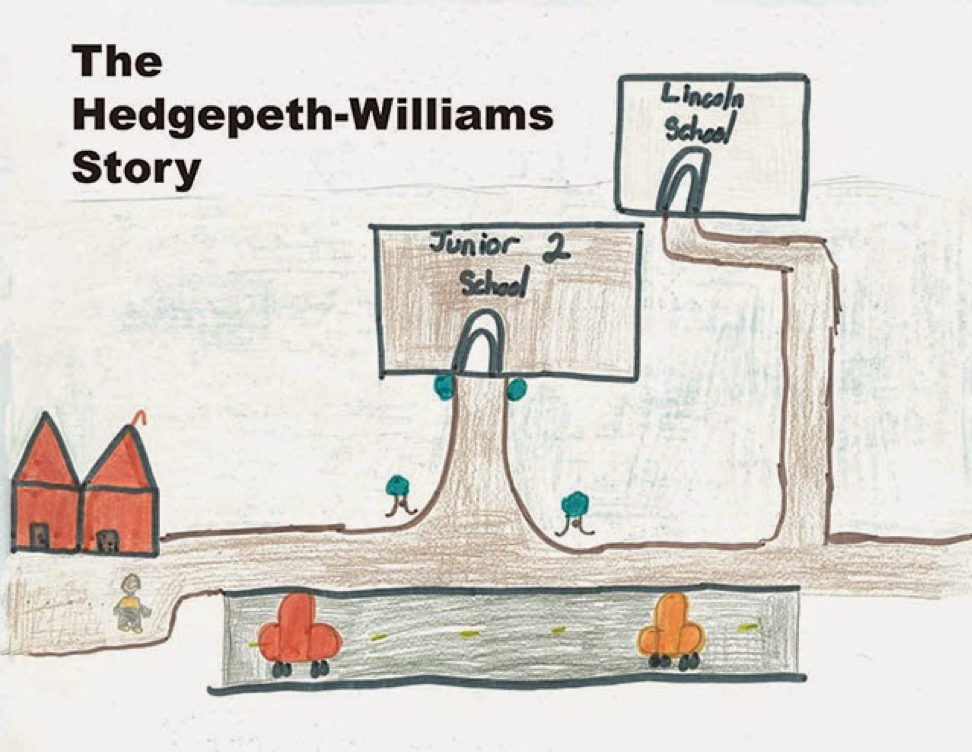

Finally, recent research found this child’s drawing of the heart of the problem African-Americans faced in the fall of 1943. Its eloquence is staggering.

Postscript

I started this search for a name and it ended with an historic decision by the Supreme Court of the United States. I still have much to learn about Berline Stephens and her accomplished family. But this is a start. It will be placed in the Stockton University Archives and never again will her name be forgotten.