Don Bragg, Stockton’s first Athletic Director

By Gabriella Fiorica

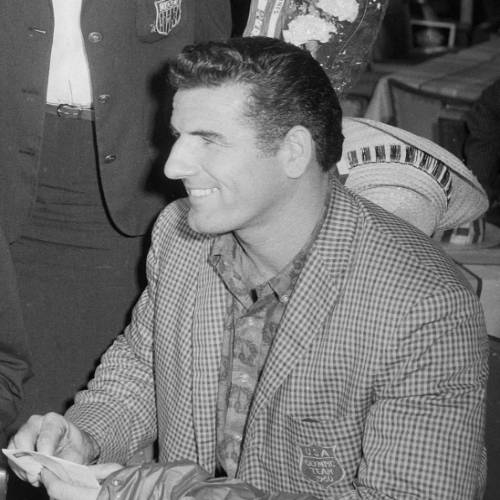

The Stockton Stories site has informed readers about many of Stockton’s firsts, especially those people who played major roles in the creation and development of the Stockton community. Readers have been introduced to the founding deans and first Vice President. They’ve read about Luanne Anton, Stockton’s first Health Educator, and Simon Mpondo, an early literature professor. Here readers are introduced to yet another Stockon first: Don Bragg, Stockton’s first Athletics Director. However, the legacy of Don Bragg far surpasses his role as Athletic Director for a small, New Jersey college. Prior to joining Stockton, Bragg was an Olympic pole vaulter and almost a Hollywood moviestar. He also owned and ran a young boys camp in the Pine Barrens.

Donald George Bragg was born on May 15th, 1935, in Penns Grove, New Jersey. He attended Penns Grove High School, and even as a young child was very active and adventurous. He often ventured into the woods, and found solace in a hideaway he nicknamed Tarzanville. There, he attempted to swing through the trees, similar to Tarzan on television. Bragg collected bamboo rods from a furniture store—they served as cores around which carpeting was wrapped—and used them as mock-poles to vault over other poles he’d place between branches. Clearly, pole vaulting was introduced to Bragg at a young age.

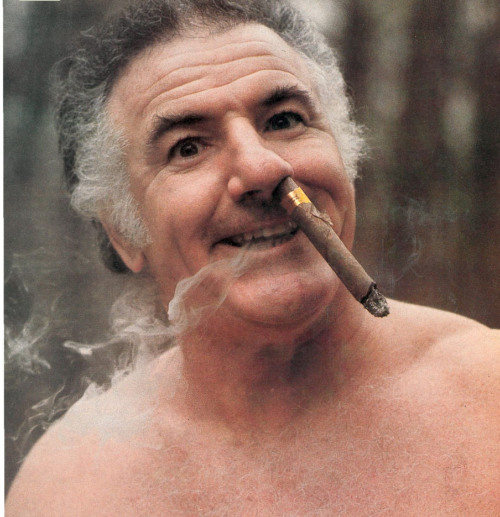

Bragg always had a fascination with the iconic character of Tarzan, portrayed in movies as raised in the African jungle by gorillas. Emulating the supposed exploits of Tarzan became commonplace for Bragg. After his Olympic success, he was offered the role of Tarzan in a movie, a dream he had had since childhood, but injuries made this impossible. One film was made with Bragg in the role of Tarzan, but because of litigation issues the film was never released.

Bragg’s desire to emulate Tarzan contributed to his pole vaulting persona, and “Don (Tarzan) Bragg”' was the name plastered on the cases that carried his poles. Brag delighted in imitating Tarzan’s well-known yell, especially after a victory. In 1959 Bragg broke the indoor pole vaulting record. He competed in the 1960 Rome Summer Olympics, winning a gold medal and breaking Bob Richard’s Olympic record by nearly six inches.

Bragg was the last world-class pole vaulter to use an aluminum pole. The much more flexible fiberglass poles, which can bend nearly 90 degrees, making higher vaults possible, weren’t introduced until after Bragg’s retirement. Aluminum poles required vaulters to exhibit great upper body strength. Bragg, weighing about 200 lbs and standing at 6’3”, showcased impressive vaulting skills for a man of his stature and mass. In fact, he was one of the largest pole vaulters in history. After breaking the record, Bragg let out his Tarzan-like yell, further associating him with the ionic character. He went on to recreate that famous Tarzan-yell in Rome in 2010, in celebration of the 50th year since competing in the 1960 games.

Some time after the conclusion of Bragg’s pole vaulting career, he and his wife opened and operated a boys’ summer camp, named “Camp Olympik.” The camp was located in the Pine Barrens, not far from where Stockton State College was soon to be developed. It didn’t take long for Bragg to hear of its development and to become interested in the job of “Athletic Director.”

Bragg joined Stockton with much enthusiasm. From the start he spoke often about the great plans he had for Stockton athletics. An article from the Argo reads, “Bragg indicated that there are two main reasons for his going to Stockton. He was high in praise for the new Vice President for Campus Programs, Jim Wickenden, and said that he looked forward to working with him.” His other reason was the location. Bragg stated, “I live in the Pine Barrens and I think that this area is tops.” Although hired for sports and recreation, Bragg wanted to develop and create additional programs and monitor that they ran smoothly: “Stockton is good because of its newness; it is growing and has great potential.” This statement comes from an Argo article published in 1972, when Stockton was quite early in its development. Bragg was correct in commenting about the “newness” of the college. 1972 was the first year that classes were conducted on the Galloway campus.

Bragg was full of ideas and aspirations. The article mentions, “Bragg indicated that plans are being made for a basketball team and a track team for 1972–1973. He also stated that a large amount of ground work is being done for the establishment of an intercollegiate football team.” Bragg was excited to introduce activities such as canoeing, hiking, and camping to the campus. Not long after being hired, he shared with the Argo possible goals for a women’s program, and expressed that he wanted to create an athletic environment that was welcoming to women. He shared, “When it comes to recreational programs, women are often slighted. I think this is wrong . . . I am currently looking into the possibility of forming a girls’ flag football team.” As will be seen below, it is unclear whether Bragg’s efforts to create an inclusive environment for female athletics continued throughout his Stockton career. During his tenure, he directed a number of activities including softball, basketball, volleyball and tennis. He was crucial in the development of intramural and intercollegiate programs at Stockton. Bragg worked as Stockton’s athletic director until June 1981.

Bragg’s time at Stockton didn’t last as long as the Olympian might have hoped. The athletic director’s career turned downhill after Sports Illustrated published an article about Bragg that showed him in a negative light. The article opened with a quote by Bragg: “I don’t make a good pet.” The piece depicted Bragg as a cocky, egotistical individual, commenting that he, “. . . continually introduces himself as ‘Don Bragg Olympic Champion.’ There is no comma. Most people have two names; Bragg has four” (Sports Illustrated). The piece portrayed Bragg badly, and, also, his role at Stockton. The piece focused on Bragg’s work with Stockton intramurals, which had been very successful. The article reveals, “Of the 3,800 students, more than 1,000 are engaged in intramurals” (Sports Illustrated). Despite at first commenting positively on the success of the program, the piece quoted Bragg as stating,“‘We got started here, finally, and had intramurals and everything was fine, especially flag football. Then, dammit, the girls wanted to play. What was I supposed to do? I mean guys are going to bust butts, right?” (Sports Illustrated). Bragg’s statements did not translate well, and readers viewed his attitude as sexist. The interview, which Bragg had been excited to conduct, ending up doing more damage than good.

In A Chance to Dare: A Don Bragg Story, Bragg’s autobiography published in 2002, he wrote that he had been surprised to hear that Sports Illustrated was interested in conducting an interview with him, considering it had been about twenty years since his performance in Rome. He stated that when he read the final article, it was nothing like the actual interview that he remembered. His memoir explains that quotes had been taken out of context, and that the interviewer had completely ignored what Bragg had been trying to say. The autobiography gives an example of this: “. . . [Sports Illustrated] quoted the first line of one of my poems, ‘All woman I do despise,’ but neglects to mention the poem ends with the idea that I prefer the company of some woman, though friendship is difficult for me” (Bragg 251). Bragg was insistent that the article had often twisted his words or coated them with sarcasm. He argued the article was filled with deceitful content.

Most of Stockton’s students and staff, however, took the article at face value, and they weren’t too happy with Don Bragg’s performance. After the article’s publication, Bragg became infamous on campus. Days after the article was released, an article in Argo commented “Don Bragg begins by stating that he has developed the ‘best intra-mural program in the country’ at Stockton. Unfortunately, this is not the case. It was not Bragg, but Nick Werkman, Intramural Director from 1972 through January 1978, who should receive the credit for developing this program.” After the interview was released, there was palpable disdain for Bragg, and students were candid in their anger toward the director. “A good place for Bragg to start this reconstruction would be his attitude toward female participation in intramurals,” one student wrote in the Argo. “It is astonishing that a high-level administrator such as Bragg was quoted in a national magazine (Sports Illustrated) as saying, ‘We finally got started and had intramurals and everything was fine . . . Then dammit, the girls wanted to play.’ Bragg went on to say the ‘real teams are all men.’ ”

All the work Bragg put into the Athletic’s program was questioned and critiqued after the publication of his interview. Students were quick to blame Bragg for Stockton’s less-than-impressive athletics department, adding, “After you read the article, you can appreciate why athletes at Stockton feel as they do and who is responsible for their frustration.” In addition to reflecting on the article, students also reflected on their own experiences with Bragg. They confessed, “When a group of women approached Bragg last softball season as to why their program had been shortened by one week, he retorted, ‘You girls are a pain in the ass. If you don’t like it, tough.’ If that is Bragg’s attitude about the people whose athletic participation he is paid to direct, not dictate, then perhaps it’s time he found himself another job.” After the Sports Illustrated article, the last thing Bragg needed was more backlash about his attitude, yet that is what he received.

After the Sports Illustrated article, word of Bragg’s possible departure from Stockton spread like wildfire. Soon enough, the Stockton administration was feeling pressure from the community to fire Bragg. An Argo article makes it clear that, “For the past two weeks, Stockton’s image as a reputable institution of higher education has been slowly twisting in the wind . . . For unless the proper authorities call Bragg to account, Stockton’s reputation will continue to be linked with his. And neither Stockton nor its student body can afford that linkage. Inevitably, it will depreciate the value of a Stockton degree.” The article goes on to state that enrollment might even be affected by this scandal, and that Stockton’s good reputation was sure to collapse if the issue of Bragg was not dealt with. The article made clear its belief that while Bragg remained at Stockton, the College would be judged guilty by association.

When addressing the uproar, Peter Mitchell, Stockton’s president at the time, told the Argo, “There is no problem,” and clarified that Bragg would be judged “by his performance as an administrator and that this will be handled by Vice President James Judy of Campus Life.” Mitchell, however, personally objected to Bragg’s negative comments and his departure was inevitable. A September 1980 Argo article, published about five months after Bragg’s interview, revealed that the the Board of Trustees had chosen not to renew his contract as Athletic Director. The article was bitter, adding that “Since Bragg contends the ‘best’ does not belong at Stockton, his departure is only fitting.”

Bragg left Stockton and pursued other goals, which make for entertaining reading in his autobiography. Bragg eventually moved to California where he lived until his death.

Don “Tarzan” Bragg died on February 16, 2019, in his home in Oakley, California, at age 83. His wife, Theresa Bragg, explained that his health had never fully recovered after stroke nearly ten years prior. Days after his death Stockton’s President Harvey Kessleman sent an email to the Stockton community, announcing Bragg’s passing. The email ended with the statement, “Don, a former Olympic Champion, was quite the character and those who knew him will never forget his wonderfully entertaining stories. Our thoughts and prayers are with his family.”

Although Don Bragg is gone, his legacy lives on. Despite the fact that many in the sports world associate his name with his famous Olympic career, the Stockton Community still remembers another achievement: being Stockton’s first Athletic Director. Regardless of the unfortunate interview with Sports Illustrated that led to his firing, nothing changes the fact that Bragg is one of Stockton’s firsts. The contribution he made to the Athletics program and the Stockton community as a whole is one more way Bragg’s legacy will live on.