Naming Lake Fred

By Tom Kinsella

“I don’t think there’s any one of us, no matter where we live, who doesn’t have a secret place, whatever it is. It’s like Oz. … There’s a nostalgia for an unlived past.” Jean Shepherd

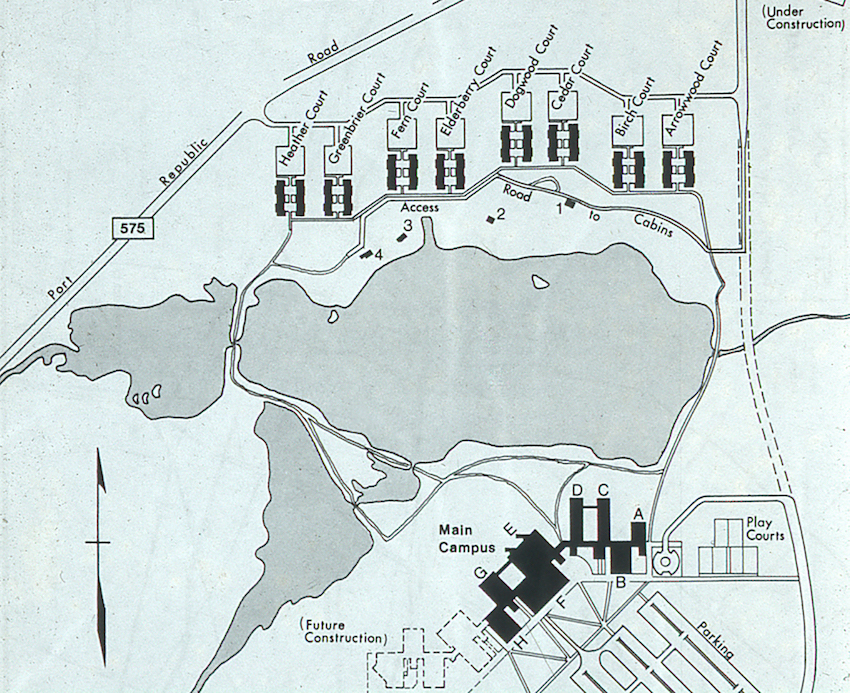

1972 Map of the Campus. See cabins 1-4 on the north shore. The courts were not completed until fall 1972.

Note the nameless lake, typical of maps from this period.

1972 Map of the Campus. See cabins 1-4 on the north shore. The courts were not completed until fall 1972.

Note the nameless lake, typical of maps from this period.

Although ocean tides rise and fall a scant ten miles from New Jersey’s Stockton University, the mighty Atlantic is not the most celebrated or consequential body of water on campus. That honor, without question, falls to Lake Fred, the one-time South Jersey cedar bog and stream, dammed in the late eighteenth century to provide waterpower for a long-gone sawmill and later worked as a productive cranberry bog. Lake Fred, actually a series of linked ponds about a half-mile long and a quarter mile wide, is the environmental centerpiece of Stockton, the original “quad” around which the campus was built. Since the opening of the University in 1971, classes have been held on the south shore of the lake.1 Student activities, many if not all, have been held on the north shore.

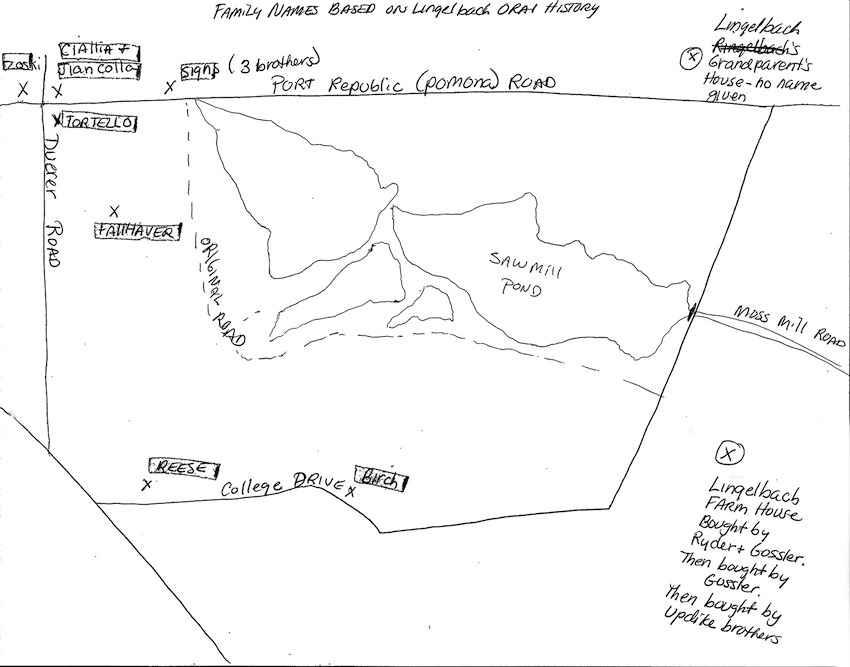

The Lingelbach map. The campus pre-Stockton, as described to Mark J. Fletcher by John J. Lingelbach.

In the early days, when the campus was new and before dorms and support buildings were built, student activities centered in and around several cabins on the north shore, the vacation retreats of previous property owners. The Hansen Cabin accommodated the president’s office, but three other cabins remained for student use. Cabin 2 housed the school newspaper, The Argo, first published in the fall of 1971; Cabin 3 hosted keg parties (among other campus activities); and Cabin 4 was devoted in part to religious services that helped foster a vibrant ecumenical fellowship. There was a Co-Op, a weight room, canoe rentals, and more. There was community. Early students spent a lot of time on the north side of the lake and today’s students do too.

In a noteworthy act of concurrence, the likes of which has not been seen since, the early Stockton community devised and quietly agreed upon a name for this central lake. In less than two years, without official proclamation, students, staff, and faculty chose the rather prosaic name that it bears today. Theirs was an act of youthful self-identification. What follows is the story of how Lake Fred got its name.

Before the arrival of students in 1971 the lake had another name. According to long-time resident John Lingelbach, who described from memory the campus landscape as it looked in the 1920s, the lake was known as Saw Mill Pond, the name conveying a cultural memory stretching back over 200 years to the first industrial use of the water shed.2

In the 1950s and 60s, the name remained in use among local residents. The families who jointly owned more than 600 acres north of the lake incorporated under the name Saw Mill Ponds.3 Stockton never adopted the name. On early college construction maps, the lake is usually depicted without a name. Sometimes it is labeled “water” or “lake.” Early building reports refer to “College Lake,” and at least once in early 1972 it was referred to as “Lake Stockton.”4 Yet by early 1973 there is no question about the name. It was Fred.

The Folklore

No official document christens the lake. No elaborate naming ceremony took place. Today, 50 years after the founding of the college, the mechanism of naming has become obscure, a matter of folklore. Still, several competing stories can be identified that purport to explain the name Fred. The first widely known story describes the naming of several campus features by early faculty member Claude Epstein, who was engaged in mapping the environment of the campus. The name, Epstein is reputed to have explained, was a whimsical choice, inspired by 1950–60s radio personality Jean Shepherd, who used “Fred” as a generic name for someone who was goofy, a dork, or a lay about. In this story the small non-lake was given a nondescript name. It had after all spent most of its history, pre-nineteenth century, as a swampy stream. The story seems plausible. Early Stockton was an iconoclastic place: it does not, however, explain the naming of Stockton’s other lake, Pam.

A second origin story describes the early campus as a kind of pastoral retreat, with wildlife, back to nature pursuits, music, even a wandering shepherd of sorts. According to this story, an early student named Fred made a habit of walking around the lake at all hours (some versions suggest two students named Fred, at least one version mentions Fred Mench, long-time Professor of Classics). Fred, whoever or however many, became a fixture around the lakeshore, fishing, playing guitar, and seeking typical 1970s inspiration. According to this story, which has come to be associated with the name Fred Sommers, the Stockton community somehow began calling the body of water Fred’s Lake, or Lake Fred. And in this story, Fred usually has a girlfriend named Pam.

Another origin story identifies an early property owner named Fred Lake whose last name, if used for naming purposes, would result in the absurd “Lake Lake,” so the full name was simply reversed. Still another suggests a connection with the influential Fred and Ethel Noyes, a local couple who developed the tourist attraction Smithville Towne Center, 4 miles from Stockton in the 1960s and 70s. They also founded the Noyes Museum of Art, once located in nearby Oceanville (now associated with Stockton and renamed The Noyes Museum of Art of Stockton University). Both are interesting stories, and again, plausible. But they have no corroboration. And of course, there is no Lake Ethel.5

Other origin tales have obviously wandered down the paths of folklore. Fred was in love with Pam. They were old-time locals or they were students (accounts differ). On a tragic day, sometimes night, Fred could no longer endure the delay of a short walk around the lake. He chose instead to swim, driven by the urgency of his love for the enchanting Pam, who waited on the far shore. Half way across the lake, in tragic style, he drowned. In her grief, Pam secluded herself along the shores of Stockton’s smaller lake, the borrow pit known ever afterward by her name.6

Examples move from historically plausible to homegrown folklore. The last, an ode to Fred and Pam, has no basis in fact other than the names of each lake. Still, it has been passed through the Stockton community for years, a fictionalized, romantic genesis tale: it is meant to entertain, not record half-remembered details from early college days. (Without question, no Fred drowned, and no Pam died in mourning.) We have moved from history to oral storytelling. But there is a history of early Stockton, and quite a bit of evidence for it is preserved in the Bjork Library’s Special Collections & Archives.

Early Campus Use of the Lake

Prospective students were drawn to the lake even before classes commenced. Ken Tompkins, the Chairman of General and Liberal Studies (the first deans were called chairmen), describes working at the Scott House in the summer of 1971. A young couple arrived at his office door and inquired about the college that would open in the fall. Ken sat them down and explained the ideas behind precepting, colloquia, collegia, coursework and self-directed majors. After his spiel they thanked him and asked whether they could see the campus. “There’s nothing built, nothing to see,” he replied, “but you can take a walk around the lake.” He gave them directions, and went back to work.

The Island. This photograph dates from August, 1971. Notice the intact dock that the students may have used to enter the water.

Later that day, James Williams, the first Director of Public Safety and Campus Security, called Ken: “Did you talk with a couple of prospective students today? Young kids?” he said. “They were in the lake swimming by the cabins – nude.” Williams told the two to get out, that he wouldn’t arrest them. Instead, they swam to the nearby island, got up among the bushes, and wouldn’t show themselves. The chief finally just left, and the couple, one who became Ken’s preceptee, found their way back to the shore and their clothes. Perhaps for the first time, students had taken a dip in the lake.

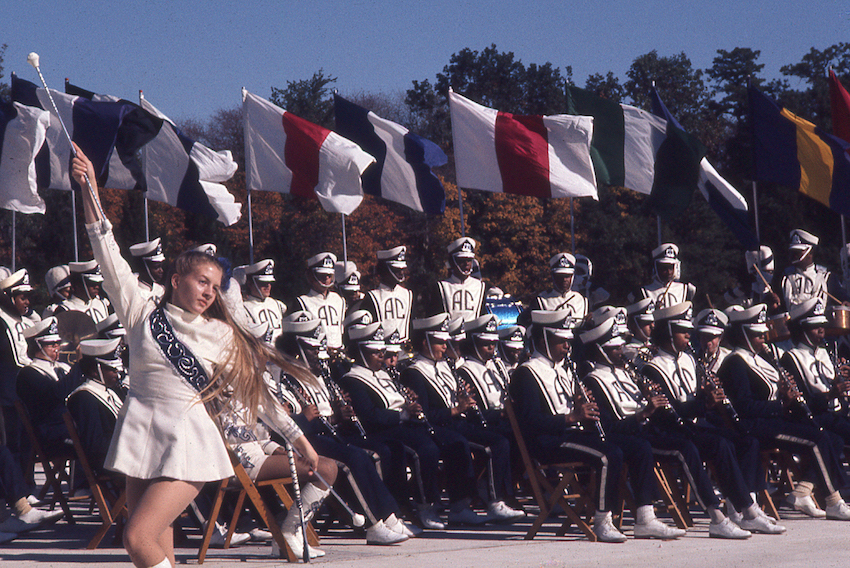

In the fall of 1971 the main campus was still under construction and not ready for use. Classes and campus activities were held in the Mayflower Hotel, in Atlantic City. Nevertheless, a well-attended celebration was held on the main campus at lakeside on October 19, 1971, billed as the First Annual Campus Day. Atlantic City High School provided entertainment with performances by the school band, chorus, color guard and baton twirlers.

Atlantic City High School Band, at the First Annual Campus Day. They were only part of the festivities.

The Governor, William T. Cahill, and the Chancellor of Higher Education, Ralph Dungan, were guests of honor. At lunch, large numbers of students, faculty, staff and local politicians enjoyed an outdoor buffet with hot dogs and standard picnic fare. Also in attendance were “every yellow jacket in Galloway,” attracted by the aroma. After lunch came the regatta. Students raced across the lake with a “crowd on the opposite shore [that] cheered wildly.” They crossed the unnamed lake in “god awful looking ‘boats,’ most of which sank before they got to the finish line.”7 It was great fun. The Stockton community, even while attending classes on the Boardwalk, was well aware of its lake.

Staff first arrived on the partially-completed campus in December 1971 and students followed in January 1972. At that time there was no acknowledged name for the lake. “College Lake” and “Lake Stockton” were early candidates, but most often it was simply referred to as the Lake. Attitudes began to change, perhaps as early as the first warm days of 1972. In a pleasant phenomenon that continues to this day, the Stockton community comes out in force on the first warm days of spring, especially the students. They enjoy the beauty of the campus as if discovering it anew. Of course, in April and May of 1972, this was literally true. Students were watching the campus blossom for the very first time.

The name “Lake Fred” is first used in print in an article written for The Argo by faculty member Dick Colby. In “Poisonous Animals and Plants on Campus” (May 1, 1972), he refers to “Lake Fred (our main lake).” The parenthetical aside seems to clue in the less well informed that the Lake has been named. By August 24 of the same year, no explanation is needed; when describing common summer activities, Argo editors mention “daily canoeing and sailing on lake Fred.”8 The advertisements for the second “Stockton Regatta” in October 1972 describe the race as taking place on “Lake Fred.”9 The January 27, 1973, issue of The Argo reported, “Ice Comes to Lake Fred,” and later that spring the first Lake Fred Folk Festival was heavily advertised. Little more than one year after students arrived on campus, by early 1973, the name had come into widespread use.

The Stockton Housing Impact Statement, dated June 27, 1979, is the first official college document found to include the name Lake Fred. The earliest official college map is dated August, 1980.10 Generic campus maps such as those used in the Bulletin (Stockton’s college catalog), stubbornly left the lake unnamed until 1984.11

Sailing on Lake Fred. One of the north shore cabins is visible to the left.

Sailing on Lake Fred. One of the north shore cabins is visible to the left.

It is interesting that by mid-1985 the name Fred had become a puzzle which merited investigation. The article “Lake Named for Fred’s Sake” in the college publication Campus Connections (May 7, 1985) suggests that the community had forgotten the origin. In a humorous article, Virginia Sandberg describes her attempts to find the true story. She is advised that Claude Epstein knows an account of it, and the bulk of the article describes her quest to contact him. Along the way she peppers the article with entertaining but unbelievable suggestions: the lake is named for Pam and Fred Pomona; the name is an acronym for Federal Reserve of Environmental Development. When finally she contacts Epstein and asks about the origin, he replies simply: “I don’t know.” He does however tell the story of the Lake family.12

If in 1972 the Stockton community understood where the name had originated, little more than ten years later it seems to have forgotten. Debate over the origin has arisen sporadically. In 2007, spurred by comments made during the annual “Myths and Legends” event, a spirited email chain wrestled between the Epstein and Fred Sommers stories.

Faced with competing and seemingly contradictory stories – both vouched for by significant portions of the Stockton community – I returned to the north shore of Lake Fred and those early cabins. The Stockton Archives hold a cache of photographic slides that document the early campus, especially early building projects. Among the hundreds of slides are two-dozen that show the cabins, now long gone, along with the social life that they fostered.

After placing scans of the slides on a blog, I queried alums, sending emails to those who graduated during the 1970s and were still in contact through Alumni Relations.13 What was life like on the north shore of Lake Fred? What were the cabins used for in those early days? Where did the lake get its name?

Many interesting conversations started up: about fishing and sailing on the lake, vacant deer stands occupied by adventurous students, the folk festival, the operation of The Argo and the Co-Op, the beloved college chaplain, Father Joe Waggenhoffer. One thread was expected: “How Lake Fred Got Its Name.”

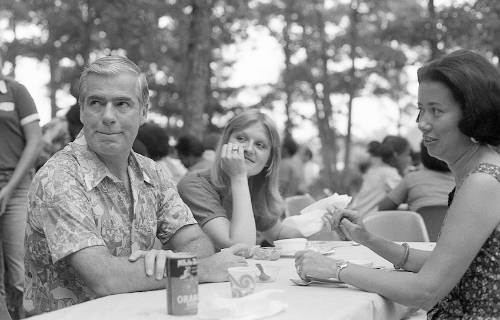

President Richard E. Bjork and his wife Joan attend the BASK picnic in 1977 with Anne

Mercado (center), who, as a Stockton student, helped staff canoe rentals on Lake Fred.

President Richard E. Bjork and his wife Joan attend the BASK picnic in 1977 with Anne

Mercado (center), who, as a Stockton student, helped staff canoe rentals on Lake Fred.

A local band playing at a Stockton cabin barbeque in 1983, not long before the cabins were demolished.

One of Stockton's many community barbeques.

A student meeting at the Co-Op.

Dates

- 1968 The New Jersey legislature approves a capital construction bond issue including funding to build a state college in South Jersey.

- 1970 The first chairmen (deans) and upper administration arrive in South Jersey and begin planning the academic structures of the college.

- 1971 When it becomes clear that buildings on the main campus will not be completed in time, the Mayflower Hotel in Atlantic City is chosen as the temporary campus.

- 1971 (spring and summer) Hiring and planning for the opening semester takes place.

- 1971 (fall) First semester classes are held at the Mayflower Hotel.

- 1971 (December) Faculty and staff arrive on the partially completed main campus.

- 1972 (January) Students arrive on campus for the first mid-term semester.

- 1972 (May 1) The name “Lake Fred” first used in print.

- 1973 (April 6-8) The first Lake Fred Folk Festival takes place.

- 1973 (July) The name “Lake Fred” appears on the Epstein map.

Evidence for Fred Sommers

Several alums suggested vague origin stories based upon a guy named Fred. Buddy Wright, an alum from the first cohort, was specific:

There was a group of us sitting around Lake Fred when Fred Summers stopped playing guitar, stood up, and announced with certainty, “I christen this body of water Lake Fred and thus it will forever be known.” Which it is. You might want to reach out to Fred for verification. That was in the Spring Semester of 1972.14

Reaching out to Fred Summers, it turned out, was no easy matter. I completed a thorough search, but there was no Fred Summers to be found (nor Frederick, nor Sommers, nor Sommer). Brick wall. Until January 2015 when I received an email out of the blue from an Eric Sommer. He related that his full name was Frederic Sennen Sommers. He now went by Eric, but while at Stockton he was known as Fred – Fred Sommers.

In a brief bio he described living with his parents in Southeast Asia in the 1960s, explaining that his parents knew Woody Thrombley, the first Dean of Social and Behavioral Sciences (and the second Vice President for Academic Affairs), and that Thrombley had encouraged him to attend the new school. So Fred came to Stockton and attended first semester classes at the Mayflower Hotel, living in a motel on Tennessee and the Boardwalk. When classes shifted to the main campus in spring 1972, with student housing not yet constructed, Fred lived off campus in several apartments: one across from Lucy in Margate, another on Rt. 30. He was itinerant, always on the move. He was an art student, mentored by early faculty member Brook Larson, “a great American painter,” and he spent his days wandering the lake in search of inspiration that he later put to use working long hours in the art studio. He mentioned that he drew the original masthead for The Argo, working with a rapidograph pen and black ink. “Look,” he said, and “you can see my name in the corner, ‘Fred.’ ”15

Having read this short biography, I excitedly wrote back to Sommer. I was quite interested in his story, I replied, but wondered whether he was also the Fred of Lake Fred fame. He responded simply: “I’ve been waiting a long time for someone to ask me that.”

It turns out that Fred, now Eric, left Stockton before receiving his degree, which had hampered my search for him among alumni records. He travelled first to Asia, then spent several years in Europe, before returning to the US to start a band. His press bio described his work with the Atomics, an influential Boston band during the 80s. It also mentioned that Eric had played with Jerry Douglas, Leon Redbone, John Mayall, Dr. John, Andy McKee, and John Hammond Jr. He had learned new licks from Nick Lowe, Steve Howe of Yes, and David Bromberg. According to what I read, Eric was an accomplished guitarist with a decades-long playing career.

On a warm night in July 2015, Eric Sommer played the Bus Stop Music Cafe, a small coffee house in Pitman, NJ, near Glassboro. I was in attendance with Jim McCarthy, an early alum and recently retired Associate Provost for Computing and Communications at Stockton. Eric played solo for a couple of hours. Although he pulled out his Telecaster for a song or two, the majority of the show was acoustic. He played several guitars, with various tunings, hammering away, and making it plain that a guitar is a percussion instrument. His aggressive finger picking and liberal use of slide created a distinctive, Americana sound. It was an invigorating show. On the road for 40 odd years, playing his own songs and those of others, Eric is an experienced and engaging performer. His lengthy but hilarious introduction to his protest song “Farmer Brown,” was great showmanship. The song itself was a showstopper.

During a break Jim and I introduced ourselves and chatted with Eric. He had many good memories of Stockton, spoke of Woody Thrombley, and laughed at the thought of Louie’s bar on Jimmie Leeds Road. I asked whether he knew where Lake Pam got its name, but he drew a blank. Jim and I bought CDs and Eric gave us posters and t-shirts and wooden clothespins reading ericsommer.com (his business cards). It was a very entertaining night. But it hadn’t answered my central question. Meeting Eric hadn’t gotten me closer to understanding how the lake had received its name. Even if he was an early art student who spent a lot of time walking around the lake, and even if he did raise a beer and with solemn rites christen the lake, how did Stockton get from those spare facts to agreement that an entire campus would adopt the name?

One way was through Woody Thrombley. In the early days of the University, the senior administrative staff was a small and tight-knit group. According to Charles Tantillo, at the time assistant to the President (he eventually rose to Senior Vice President), they enjoyed a good deal of teasing among themselves, busting on one another, especially during weekly senior staff meetings.

Thrombley was invariably asked at those meetings about his preceptee Fred Sommers. With total enrollment still small (1,604 in 1972), it was easy pickings for the senior staff to rib the strait-laced dean about his free-spirited preceptee. Had Woody seen Fred lately? His typical response was, “Fred is fishing at his lake.” (Indeed, Eric has confirmed that he fished the lake quite a bit.) In time, according to Tantillo, the senior staff and others began to refer to the lake as Fred’s Lake and then Lake Fred, and from there the name informally incorporated itself into the language of Stockton.

Another vehicle for the name was the student run newspaper, The Argo. Eric Sommer had mentioned that he had drawn its first masthead. Indeed, an odd but ornate drawing of a Greek ship on wheels, loaded with the word ARGO, appears atop the third number of the newspaper, December 1, 1971, and “Fred” is neatly penned at the lower right corner.

Beginning with that third number, Fred Sommers is listed as artist in The Argo staff guide (one of three); he remained listed until October 4, 1972. Examples of his artwork are easily identified, and at times his peripatetic and artistic natures converged.

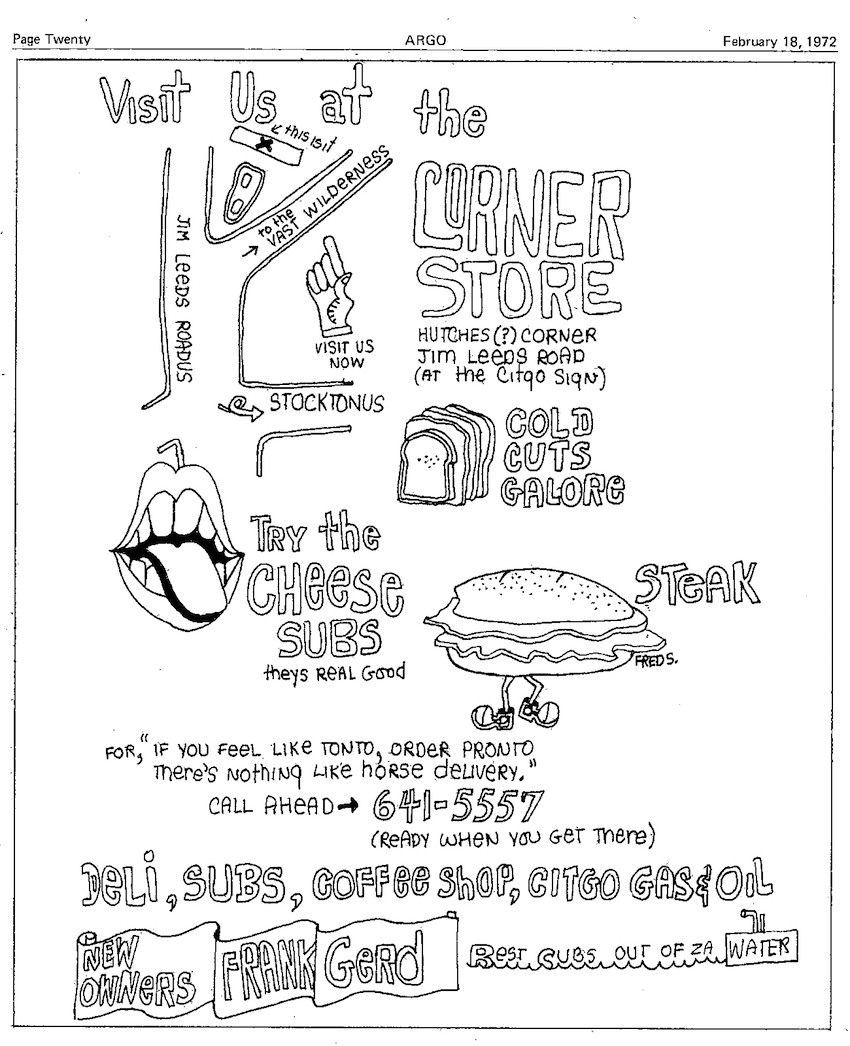

In early 1972 Frank Groves and Gerd Hinrichs, two transfer students from Ocean County College, opened The Corner Store at the triangular corner of Jimmie Leeds and Duerer roads (Jo Jo’s today). After stocking their shelves, Groves and Hinrichs turned to remodeling the store, building a coffee house corner, with stage for “rap sessions on far ranging topics.” Poetry readings, music, and improvisational theatre were encouraged.16 Walking to and from campus, Fred describes stumbling upon The Corner Store. Not only did he help build the stage so that he and others could play live music for Stockton students and locals, but he drew several advertisements for the store. Perhaps his most visually appealing advertisement was first seen in the February 18, 1972 issue of The Argo.17

One of Sommers' many hand-made advertisements for The Corner Store.

One of Sommers' many hand-made advertisements for The Corner Store.

Members of the early Argo staff and their friends (notably Dan McMahon and Jose Delgado) have long attested that the lake was named after Fred, based on his ubiquitous appearances along its shores in the spring of 1972. They also remember (with reasonable though not complete clarity) that Fred had a girlfriend named Pam. According to them, she was a blonde-haired beauty who liked to sun bathe nude, and did so frequently at Stockton’s more secluded lake – Lake Pam – tucked away from the academic buildings, and reached only after a hike of about a half mile into the South Jersey woods.

But I had asked Eric about the naming of Lake Pam and he had professed ignorance. Dan McMahon, hearing this, replied, “Fred does not remember a lot of things.” So I took another shot, writing Eric and reminding him that both Dan and Jose remembered his girlfriend Pam. My note elicited the following excited response: “WHOA!!! WHOA!!! … Dude, it was Pam H.18 I forgot all about that– her first name is Pam and I knew her from The Mayflower . . . Pam and I were always in the woods, spending hours up in the deer platforms that were everywhere in the lake woods in those days.” So there was a Pam, and she was a beauty– “a cross between Farrah Fawcett and Linda Ronstadt – blonde with huge green eyes,” remarked Eric.

Eric went on to describe his life during the crucial spring of 1972. He first shared a rental in Margate with Norm Einhorn and Jose Delgado, close to Lucy the Elephant. Einhorn described, “a nice little house with a quasi-finished attic,” where Fred crashed for the first couple months of the year.19 According to Einhorn, one evening in the attic he and Fred began chatting about naming the lake. “If you ask for names through The Argo,” said Einhorn, “you’ll get a bunch of silly ones.” He remembers turning to Fred and suggesting, “Just name it after yourself.”

After that Fred lived in a cheap motel on the White Horse Pike with Peter Dungan, son of the New Jersey Chancellor of Higher Education. It was a forty-five minute walk to the main campus through the Pine Barrens; without a car, it was a trek he made daily.

From comments of early alums and from Eric’s emails, a picture of a young and lonely Fred Sommers comes into focus. He could not return home at the end of semesters – not to his family in Southeast Asia. On weekends the campus cleared out, and with no particular place to go (he could only visit Woody Thrombley so many times), he usually ended up wandering the woods, spending hours on the hunters’ platforms high in the trees reading R. D. Laing’s Knots or bushwacking through the woods. It was either that or, as he describes, “hitchhiking around trying to find people who knew strange guitar chords … [I] really lost myself in that stuff.”20 He probably seemed an aimless, back-woods figure to anyone in the Stockton community who took notice. In many ways, the woods of the unfinished campus became his home.

Artwork in the F-wing art studio. c. 1972-1973, Fred Sommers poses with three of his Stockton paintings. The work in the middle hung in Woody Thrombley’s office.

For Fred, on his own at a Jersey state college, introductions were awkward. Whenever he described his background – the International School of Bangkok, St. Joseph’s College in Darjeeling, India, and finally Lexington High in Massachusetts – no one really believed him. Fred did not fit the demographic of a typical Stockton student (not then, not now). He was adrift and needed something to hang onto. If on a day in the spring of 1972 he stood by the lake and saluted it using his name – he was only trying to anchor himself and his experiences. For a time, Lake Fred and Stockton provided that anchor. But Stockton could not or would not keep Fred for four years. He left after the spring of 1973, having completed 60 credits, to return to Asia and his parents. His father, William A. Sommers, a Harvard Fellow and graduate of The Littauer Center of Public Administration (now the Kennedy School of Government), had been called in the early 1960s to join the US Operation Mission to Thailand as a public administrator. During the years when his son attended Stockton, Sommers worked in Saigon; he did so right up to the end of the war, trying to put things back together after the Tet Offensive. He wrote literary criticism and poetry in his down time, drawing inspiration from the eastern countries where he lived and worked. Joan Pokorney Sommers, Fred’s mother, was equally accomplished, a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago and a painter “known for uniquely fusing the tensions of abstract expressionism with the principles of eastern aesthetics.”21 It is not surprising that Fred felt the pull of the Far East and returned to it.

He planned a semester-long academic project based on a trip to Vietnam: he would chronicle the country through photographs, descriptions, observations and commentary. Despite Stockton’s avowed support for individualized curricula, Fred’s advisors and fellow students could not understand the project. All they heard was that he wanted to go to Vietnam. No one would help him to develop the proposal for credit and no one in the Art program wanted much to do with him once they learned where he was headed. Fred wrote, “They ridiculed me in class, they were angry, and many were outright hostile – remember, it was Vietnam, it was Nixon,and the Kent State shootings were very, very fresh, and anyone associated with the war, no matter how innocent the connection, was a target.”22

In the end Fred just left the college and travelled to Vietnam, and eventually to Hue, DaNang, Saigon, Bin Hua, Dalat, Pleiku, Khe San, NaTrang, up to the DMZ and over to the Cambodian border. It should have been a hell of an academic project. Instead it was the beginning of Fred’s life after Stockton. Still, for a time, the college and particularly the grounds around Lake Fred had been his home, however imperfect. Lake Fred both anchored and inspired the young artist. It helped launch him on his long, iconoclastic and productive career. What other college can claim such an inspirational landmark? Such a centerpiece? It would be wholly appropriate if the name of Stockton’s lake reminded us of nature’s ability to hearten and inspire.

Evidence for Claude Epstein

Dan Moury, the first chairman of NAMS, now the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics at Stockton, was instrumental in hiring the inaugural members of NAMS, including Claude Epstein. When money was allotted during the summer of 1971 for program coordinators to write course descriptions and assign faculty loads, Moury instead petitioned to bring his new hires together for two weeks – all thirteen. It was a stroke of community-building genius. Together they would plan the trajectory of the sciences and math at Stockton. It was a young group – probably the youngest division at the school. It was almost certainly the most radical. Describing this time, Moury has referred to OBQ as an important factor in his hiring decisions. Each candidate was to have an identifiable and strong Odd Ball Quotient. History suggests that each of the early NAMS hires met this requirement in his or her own special way. Youth, radicalism, and idiosyncrasy – all helped to set the NAMS faculty apart from many other inaugural hires. During their retreat at Moury’s house (no facilities were yet available on the main campus or at the Mayflower), they worked together and they bonded. The time was exciting, and the group began to dream the dream of what Stockton could become.23 Epstein, hired as Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, was sold on Stockton when he was told that it would be an experimental college like Hampshire College. Stockton would be the “Antioch of the forgotten American.”24 It was a heady vision at the opening of a new decade. Epstein looked forward to teaching non-privileged students in a progressive setting. Working with his NAMS colleagues, planning the science and mathematics curriculum in the summer of 1971, he believed that the future of this newcollege set amidst nearly 1600 acres of Pine Barrens landscape was both innovative and promising.

Upon arrival at the college, Epstein was asked to complete a hydrological survey of the campus and adjoining watersheds. Sewer service did not yet extend to the rural campus, a situation that needed to be remedied before the college could open. The decision was made to employ a creative and rather experimental sprayfield technology. Sewage from the campus, and eventually the dorms, would be pumped several hundred yards to a processing tank, lightly chlorinated, and then intermittently sprayed on a 650 x 650 foot site to the east of College Drive, across from Parking Lot One and not far from Lake Pam. One hundred inches of treated water were to be dispersed through the sprayfield annually, and such an environmental modification needed to be studied.

The Sprayfield. A photograph of the sprayfield in use in March, 1973.

The Sprayfield. Another view of the sprayfield in March, 1973.

As early as January of 1972 (The Argo reported unseasonably warm weather that month), both Fred Sommers and Claude Epstein were walking the paths and backwoods of Stockton. Epstein, joined by students, tested soil, drove test wells, and mapped the geological configuration of the campus. As the spring semester progressed, he shared his work with colleagues. In the fall of 1972 and spring of 1973, he developed his preliminary findings in a report submitted to both the U. S. Forest Service and the Office of the President on campus. A copy in the Archives is stamped, “Received Jul 12 1973 President’s Office.”

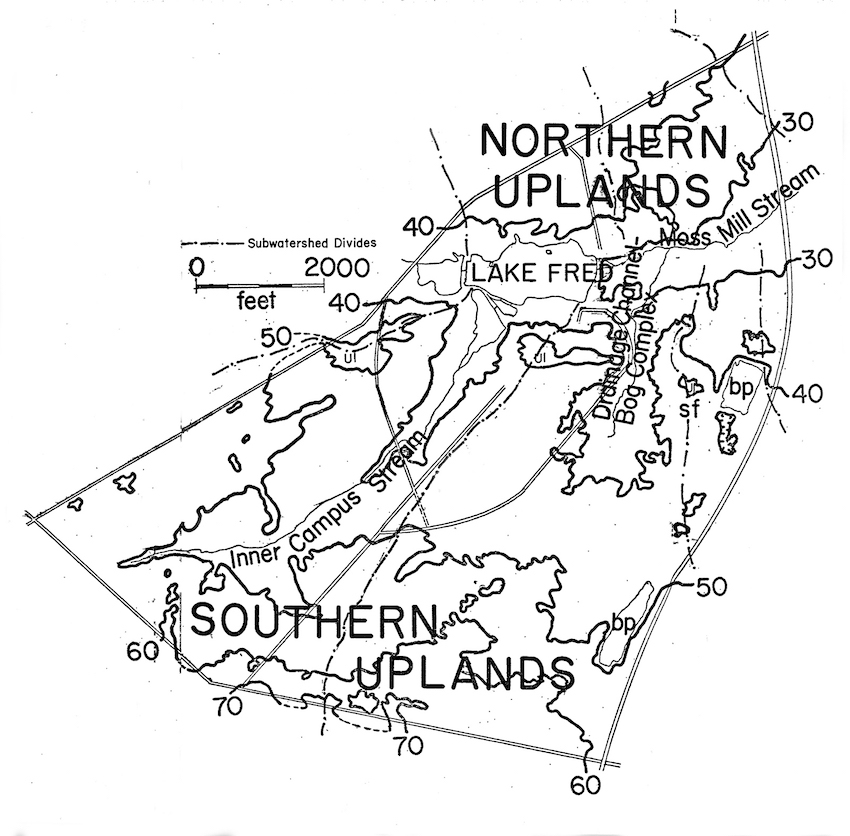

The first map in that report, an overview of the campus, labels the lake in large uppercase letters, “LAKE FRED.” It is a major piece of evidence upon which Epstein stakes his claim to naming the lake. But the familiar question remains: why choose the name Fred?

The Epstein Map. Claude Epstein’s map of the campus, created in mid-1973, is the first map to use the name. Lake Pam, to the east of the sprayfield (sf) is labled bp for borrow pit.

For years Epstein has stated, when he could be persuaded to discuss the matter at all, that he chose “Fred” as a nod to Jean Shepherd, the noted American raconteur who used radio, and later television, as his medium for storytelling. Shepherd is perhaps best known for the seasonal classic A Christmas Story, which he co-wrote and narrated. But in the 1950s and 60s he was regionally famous for his radio show on New York City’s WOR. Late night he spun humorous, sharp-witted stories with twisting and elliptical plots, often stretching the length of his 45- or 60-minute shows. His wry, seemingly spontaneous humor, with its sardonic undercurrents, brought him an avid fan base, among them young Claude Epstein, who has suggested that he was a child skeptic growing up in New York City. Shepherd’s radio program, with his fun but edgy storytelling, fed that skepticism and fostered Epstein’s wit. Shepherd often used the name Fred on his broadcasts as a generic reference to someone who was fake or goofy. In wider use the reference was not entirely fun, but had pejorative coloring: The Dictionary of American Slang defines Fred as “a despised person, a geek, a jerk.”25

It seems odd then, that Epstein should apply that name to the centerpiece of the Stockton experiment, its showcase lake. It also seems odd that for many years he seemed to distance himself from this story. That he is connected with the name is undeniable. Most of the old-time NAMS faculty, well-versed in both the campus environs and folklore, believe that he named the lake, and many suggest that they became aware of the Fred Sommers story only many years after Epstein drew his map.

The key may lie with Dick Colby, another of the original NAMS faculty members. Research suggests that he was the first to use the name in print, in his article on “Poisonous Animals and Plants” in the May 1, 1972 issue of The Argo. To the best of his recollection, Colby insists that he did not know the Fred Sommers story until years later. Instead, he referenced the new name in 1972 knowing that Epstein was mapping the campus and because he admired Epstein’s sense of humor. John Sinton, another early NAMS faculty member, explained the joking manner of the name: the lake was really just an out of use cranberry bog – it wasn’t a lake. And in Shepherd’s usage a Fred was a fraud, a fake.26

Colby’s article makes it clear that Epstein was referring to the lake as Fred quite early. In October 1972, in a letter of recommendation for Epstein’s first retention file, Colby refers to Epstein’s on-going sprayfield study, and then writes, “His sense of humor helps keep us going – e.g. Lake Fred.”

Another notable feature that Epstein named is the tributary stream that flows across the center of campus, through the cedar swamp behind Parking Lot Seven, and which empties into one of the smaller ponds feeding Lake Fred. According to Epstein, the name Cedick Run (“see Dick run”) was inspired by the Dick and Jane readers that were a staple of American classrooms from the 1930s through 1970s. They were the conventional, if uninspired workhorses of staid twentieth-century reading pedagogy.

Epstein did more than name Lake Fred and Cedick Run. In the vein of Shepherd, he contrived, as he puts it, two “cock and bull” stories to accompany the names Fred and Cedick and to provide them with historical and cultural reality. His first invention was the story of Fred Lake, the local property owner whose name when reversed named the lake. The second was his comment that Cedick is a combination of the words “Cedar and Ticks,” appropriate since the watershed has “its share of both cedars and ticks.”

One of Epstein’s hopes was that the names Lake Fred and Cedick Run would eventually be used on official U.S. Geological quadrangle maps. He knew that, in order for local place names to become eligible for inclusion, common usage was an important criterion. Epstein shamelessly obfuscated about naming the lake for thirty-five years, and at intervals offered the cock and bull stories, because he wanted the name to derive from common usage, not from lettering placed arbitrarily on a map.

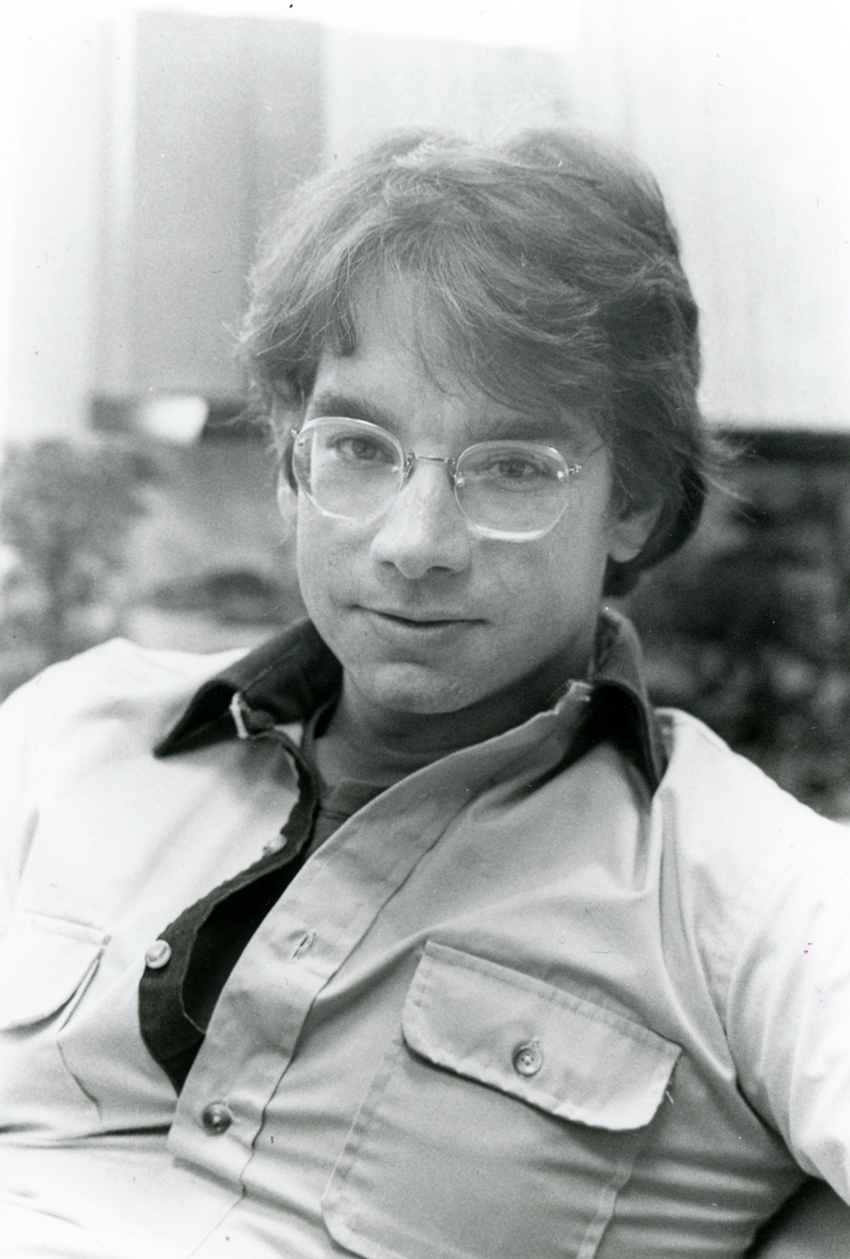

Claude Epstein around the time of the naming.

If this is the true origin of the name Lake Fred, then Epstein has been remarkably successful in his campaign. He was also fortunate that Fred Sommers, a notable campus figure, coincided in time and place with the naming. Fred and Cedick have certainly stood the test of time and are imbedded in local usage. If not yet noted on U.S. Quadrangle maps, they have at least made their way onto Google and Bing maps.

Too often, however, Epstein’s names are taken as nothing more than witty, if odd, sallies of humor. Carefully considered, they are more suggestive; something lies beneath their humor. Like Shepherd, whose stories had undertones and complexity for those who would listen, Epstein’s names suggest at least modest disenchantment with the college that he was hired to help invent. Why name the dominant body of water with a pejorative slang term and the central watershed after an unimaginative child’s reader?

Epstein has stated that early in his career he saw and challenged actions taken by the State and college – actions that undermined Stockton’s promise as New Jersey’s “environmental” college, the only four-year college in the ecologically sensitive and significant Pine Barrens. His challenges were not always heeded. And not all of his colleagues outside of NAMS were interested in bold experiments in higher education. Many were perfectly happy recreating what had gone before. Is it too harsh to suggest that they were fakers or frauds or that they preferred the staid, traditional methods of education, perhaps regressing to the point of See Dick Run?

Epstein tells the story that after Jean Shepherd had been fired from WOR, he hosted a television program in the 1970s on the New Jersey Network, Shepherd’s Pie. Shepherd encouraged viewers to send in common items for a regular feature, the “People’s Time Capsule,” and Stockton students sent in a t-shirt from one of the early and popular Lake Fred Folk Festivals. On a night that Epstein was watching, Shepherd held up the t-shirt and exclaimed, “It figures there would be someplace named Lake Fred in New Jersey.” It was then, Epstein stated, that he knew the name had stuck.

Conclusion

It is not surprising that the early Stockton community neglected to note or use the local name for its lake, Saw Mill Ponds. Early faculty have stated confidently, “Since the lake had no previous name, one had to be invented” and “We were inventing the world – we had no time for what had come before.” Many in that early Stockton community came to deeply love their campus in the Pines, but they were newcomers to the area, and at least partially cut off from the local community. Accordingly, it was easy for them to draw maps that labeled the center of campus with “Lake” or “Water.”

Rapidly, however, the Stockton community felt the ageless pull to name its surroundings. Their choice of name mirrors the lake itself. Two tributary streams feed into Lake Fred: Cedick Run from the southwest and Moss Mill Creek from the northwest. Two stories – one remembering Fred Sommers, the other Claude Epstein’s nod to Jean Shepherd – flow to a common end, the name of the lake. The details behind the stories also remind us that the college experience, whether attending a college or building one, is demanding and uncertain.

Can we point with certainty to one story as having primacy? Fred Sommers v. Claude Epstein. Perhaps not. But we can take note of the reason for the dispute: the attraction and power of the lake. Eric Sommer puts it well:

“Let’s get back on the highway of truth and beauty, of noble thought and noble emotions, ideals that named – and hence created – the idea of Lake Fred. It is a place of beauty, a place to think the big thought, a place to recharge the soul, to think clearly, to expand the heart and soul, to become part of – however briefly – the nature that is all around it; it is solace for troubles, it is a sanctuary for bruised hearts and souls … it gives strength and beauty effortlessly without asking anything in return.”

Eric Sommer casually posing for a photo.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Eric Sommer, Claude Epstein, Louise Tillstrom, Paul W. Schopp, Jack Connor, Ken Tompkins, Tony Marino, Charles Tantillo, Dan McMahon, Jose Delgado, Norm Einhorn, Jim McCarthy, Anne Mercado, Harvey Kesselman, Buddy Wright, Rugby Frank, Sara Faurot, James Pullaro, William Hamilton, Dick Colby, Sandy Bierbrauer, Fred Mench, Dan Moury, John Sinton, Karen Diemer, Peter Dungan, Lisa Honaker, Susan Davenport, Linda Stanton, Mark Demitroff, David Pinto, Lorraine Jordan, Wayne Ward, Eddie Horan, Stephanie Allen, Susan Allen and Christine Farina.

These people provided valuable information and aid in my research, and yet the project could not have been completed without the use of the Richard E. Bjork Library’s Special Collections & Archives. The Archives collect documents of historical import to the founding and development of Stockton University. If you have such documents and would be interested in donating them, please contact Heather Perez in the Bjork Library to see whether the Archives can accept them (they will not accept multiple copies of documents already preserved or documents deemed beyond the scope of the collection).

Eric Sommer can be contacted through his website, www.ericsommer.com, and email at eric@ericsommer.com. Please feel free to reach out to him.

Endnotes

Epigram. Quoted by Gerald Nachman in Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s (New York: Pantheon Books, 2003), 271.

1 The University opened as the Richard Stockton State College and was commonly referred to as Stockton State College. In 1993 the name waschanged to the impossibly long and nearly iambic The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey. In 2015, having achieved university status, the name was changed to Stockton University.

2 John J. Lingelbach provided Mark J. Fletcher with details for this map in 1978. See The Fletcher Project: Stockton State College History in Special Collections & Archives.

3 Lorraine Jordan and Wayne Ward, grandchildren of George Barlow who owned a chicken farm about three-quarters of a mile down Pomona Road from the lake (where the Stockton ball fields are now situated), grew up around the future campus during the 1950s and 1960s and knew the lake as Sawmill Ponds. The Five families who incorporated – Hansen, Burgess, Glenn, Clark, and Kirkman – were joint owners of 612 acres on the north shore and incorporated under the name Saw Mill Ponds.

Another name suggested for the lake at this time is Moss Mill Lake, but that name is more often attributed to the small lake, downstream and off campus, that is the final stop on Morses Mill Stream before it enters into Nacote Creek at Port Republic.

Acquisition of the land that now comprises Stockton’s main campus was not without contention. For an intriguing discussion see Report and Recommendations on Property Purchase Practices of the State Division of Purchase and Property. A Report by The New Jersey State Commission of Investigation, June 1972 (readily available on the web). For the suggestion of the name Moss Mill Lake, see the article “Watch on Lake Fred” by Bill Irwin; Argo, 21.8 (November 7, 1980) 13.

4 Argo, 3.4 (March 3, 1972) 2.

5 Members of the Lake family did live in Atlantic County, although none appear to have lived close to Stockton’s campus. The early Lakes lived in “Egg Harbor Township,” a rather nebulous description in early Atlantic County history.

Later members of the family lived in Pleasantville and closer to the campus. The Lakes intermarried with the Blackmans and the Leeds, among others. Included in the numerous Lakes from the area was one Simon Lake, inventor of the modern fully submersible submarine for the United States Navy in 1894.

6 Lake Pam is a borrow pit, created through excavation to obtain fill for use in the nearby Garden State Parkway.

7 The yellow jackets are described by Claude Epstein in an email dated August 11, 2015. The wildly cheering crowd is described in “First Annual Campus Day,” Argo, 1.1 (October 29, 1971) 3. Ken Tompkins described the “God awful looking boats” in an email dated August 11, 2015.

8 Argo, 2.6 (May 1, 1972) 7, 9; Argo, 4.3 (August 24, 1972) 15.

9 Argo, 5.2 (October 4, 1972) 5.

10 A copy of the Stockton Housing Impact Statement can be found in Special Collections & Archives. The first map identified is the Stockton State College Physical Master Plan, “Soccer Field Site,” updated August 1980.

Charles Tantillo has suggested that the name Lake Fred was first used on an early facilities master plan submitted and approved by the Board of Trustees and later submitted and approved by the Pinelands commission. I have not found a facilities plan before 1979 that mentions Lake Fred, though one may exist. Given that the Pinelands Commission came into existence c. 1979, the details that Tantillo remembers are probably correct. Email from Charles Tantillo, July 23, 2015.

11 The map makes its first Bulletin appearance in the Stockton State College 1984-86 Bulletin.

12 Virginia Sandberg, “Lake Named for Fred’s Sake,” Campus Connection (May 7, 1985) 11. Seecopy in Special Collections & Archives.

13 The blog can be found at https://blogs.stockton. edu/lakefredcabins/.

14 Email from Joseph “Buddy” Wright, November 17, 2014.

15 Email from Eric Sommer, January 8, 2015.

16 The first The Corner Store advertisement drawn by Fred appears in Argo 2.3 (February 4, 1972); the last using his artwork appears in Argo 5.7 (November 8, 1972).

17 “Stockton Students Buy a Corner,” Argo 2.5 (February 18, 1972) 5. Quotations are from this article.

18 Eric supplied a last name, but as I have not been able to locate Pam to ask whether she would mind being identified, she will remain Pam H. Email from Eric Sommer, August 1, 2015. Pam if you read this and would like to claim your rightful place in Stockton history, please contact me at thomas.kinsella@stockton.edu.

19 Phone conversation with Norman Einhorn, August 17, 2015.

20 Email from Eric Sommer, August 1, 2015.

21 “Joan Sommers,” Obituary in the Duluth News Tribune (2013). http://www.duluthnewstribune.com/content/joan-sommers-1.

22 Email from Eric Sommer, August 1, 2015.

23 Daniel N. Moury, “Different from theBeginning—NAMS,” Reaching 40: The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, eds. Ken Tompkins and Rob Gregg (The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, 2011), 35-42.

24 Email from Claude Epstein, August 11, 2015.

25 The Dictionary of American Slang, by Barbara Ann Kipfer and Robert L. Chapman, 4th ed. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007). The editors suggest a derivation dating from 1980s student use, based on Fred Flintstone. Eric Partridge, the eminent British etymologist, lists “Fred” under Australian usage in the early 1970s, defining it as “The ordinary, unimaginative Australian; the average consumer.” Partridge, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English,8th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1984).

26 Phone conversation with John Sinton, August 13, 2015.