The Bjork-Riesman Correspondence: 1972-1973

By Ken Tompkins

Preface

I came to start Stockton in 1970. As the first Dean of General Studies, my task was to develop a definition of General Studies and to put it into effect when the College started. It took all of us early administrators – the deans, vice president, president and others — 15 months to create our Divisions and to hire faculty to staff them. In 1974, I left the Deanship to teach full time. I have taught full-time for over 50 years. In 2010 I was asked — along with Rob Gregg — to organize essays on the history of the College; the result was Reaching 40.

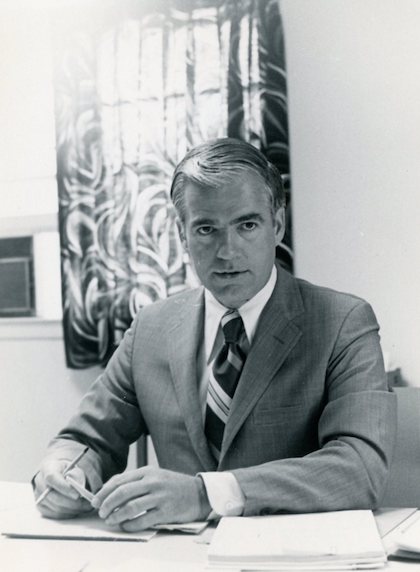

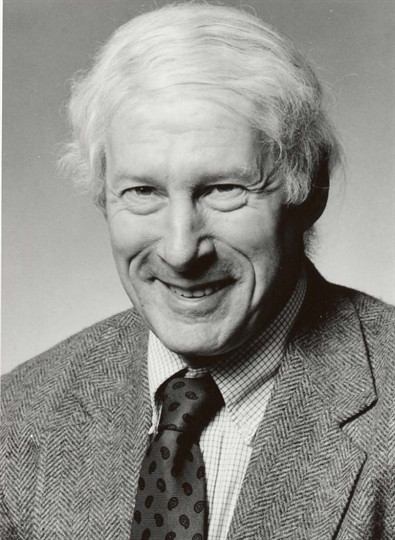

In 2018 I was asked by the 50th Anniversary Project to write something about the rather extensive collections of letters between Dick Bjork, Stockton College’s first president, and David Riesman, a well-known and eminent sociologist, between 1972 and 1973. Dick Chait — Bjork’s personal assistant — also wrote a few letters to Riesman.

After spending considerable time reading the letters, I struggled to find a pattern that would help me link these disparate materials into a coherent whole. The letters were simple enough: put them in order by date and read them in that order. I had hoped I would understand their relationship after finishing the task.

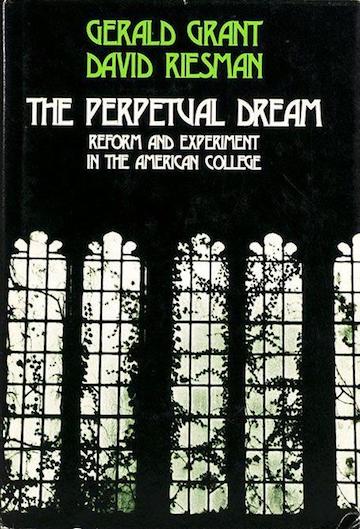

But there is also Riesman’s book — The Perpetual Dream (1978) — in which he writes about experimental colleges of the 1960s and early 1970s. The list is long and impressive:

- St. Johns

- Kresge College

- The College for Human Services

- New College

- Cluster Colleges at Santa Cruz

- Stockton College

- Ramapo College

Riesman notes that his concern is to be more descriptive than prescriptive as he examines each of these institutions in depth.

There is also Harold Hodgkinson’s study Campus Senate: Experiment In Democracy (1974) which analyzes the attitudes of three groups on the Stockton campus: the administration, the faculty and the students. Riesman mentions this study in The Perpetual Dream (345) and because it is coincidental (the research was done in 1972) with the research in the book on Stockton, it also needs to be considered here.

These three sources don’t exactly fit together. Riesman, for example, is very positive about Dick Bjork in the letters but is less so in The Perpetual Dream. It is difficult, given the sources at hand, to understand what caused his perceptions of Bjork to change so radically.

Then there are the strong comparisons between Stockton and its sister school — Ramapo College. It is clear to me that Riesman had very positive ideas about Ramapo, though he does voice a few concerns. There is little that Riesman likes about Stockton. He generally likes the administrative team, doesn’t concern himself about our students and, again, comes down hard on the President.

My sense, then, is that it will be hard to link these sources. What is missing is evidence for why attitudes changed.

The Visit

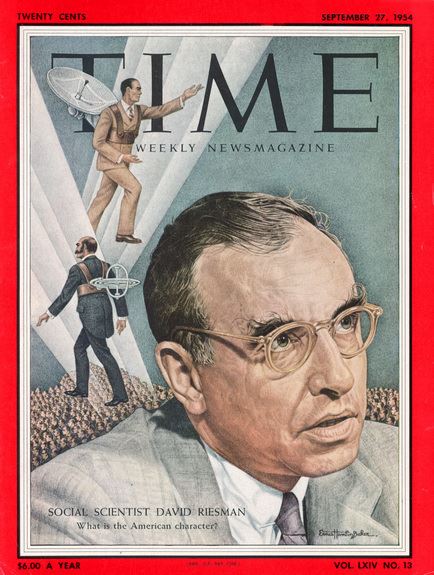

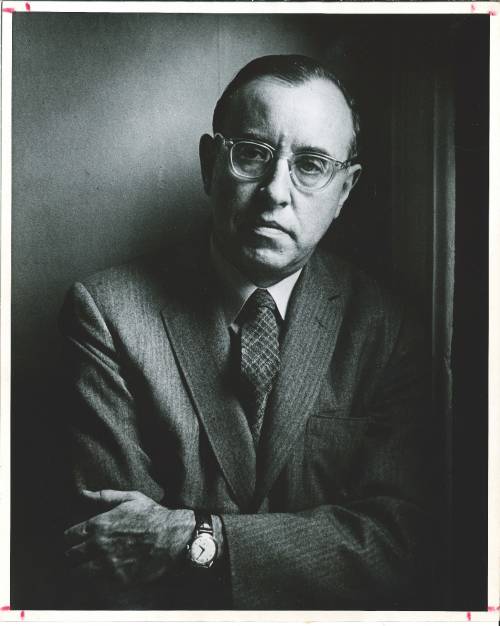

In mid-November 1971, Richard Bjork received a letter, dated on November 10, from David Riesman who was at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. Riesman was arguably the most famous sociologist in America. His book The Lonely Crowd sold 1.4 million copies.

In the letter, Riesman suggests a meeting with Bjork at Princeton. He closes the letter with “I have been working on new and experimental colleges under a Ford Grant for some time, and I have a particular interest in new State colleges such as yours.”

Bjork responded on November 30, 1971; in the letter he writes:

Stockton has been put together in a thoughtful way. First indications are that it will hold together nicely and will anticipate the future with reasonable style and good sense. Our greatest concern is that the people ‘inside’ the college will set in motion — perhaps innocently — the mechanisms which will either give Stockton instant traditions or seduce us into the familiar ways.

This exchange initiated a two-year correspondence, two chapters in Riesman’s work The Perpetual Dream, and a study on the faculty, administration and student attitudes about Stockton in 1974.

Bjork must have met Riesman in Princeton on either December 2 or 8 because by December 14 Riesman was thanking Bjork for their meeting and Bjork was sending a list of documents: Planning Seminar, Black Conference, Faculty Summary, Campus Conduct Code, Student Life Working Papers and Academic Working Papers. After a brief exchange they agree on March 20, 1972, for Riesman’s visit.

Riesman and his co-author Gerald Grant followed a pattern in the seven institutions they studied:

- Make contact with high administrators in the target institution.

- Arrange a visit to the target institution.

- During this visit, interview as many members of the institution as possible

- Collect documents and notes from the institution

- Save everything for the later writing process.

The President’s office wrote the interview schedule for the three days — March 20–22, 1972:

I met with Riesman twice: once on March 20, from 2:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m., and then again on March 22, from 9:30 to 11:00. I have to admit I only have a very general recollection of these meetings. My sense from the General Studies meeting is that he was not impressed.

The Book

Riesman and Grant began work on The Perpetual Dream in 1969 and started college visits in 1970. It was published in 1978. Riesman’s most famous work was The Lonely Crowd, which was published in 1950. His other work analyzing academia is The Academic Revolution, published in 1968.

The Perpetual Dream is divided into two sections: the first which considers “telic” institutions and the second which analyzes popular reforms of a group of institutions including Stockton and Ramapo.

Riesman’s defines “telic” as “attempts to change undergraduate education which embody a distinctive set of ends or purposes” (2). A telic college would be one where very specific results were anticipated. An example would be St. Johns. The desired results shape the curriculum that will produce them.

The second part of the book reviews the “changes in the character of undergraduate education which are the result of increases in student autonomy, new patterns of organization, and attempts to respond to the demands of minorities and other previously disenfranchised groups” (2). This second type realizes changes in the outside culture and then responds with a curriculum that confronts them. Stockton would be an example.

Attitudes

A cursory look at all of the correspondence suggests that Dick Bjork and Riesman liked each other. On January 27, 1972, Riesman writes: “If you sign yourself ‘Dick’, I must be ‘David’ to you.”

Bjork offered Riesman and his wife a room in his home when they visited. Riesman responds: “We are touched at your wanting us to stay with you — ordinarily, we find it quieter to stay at a hotel.” He describes his other needs in this letter from February 16, 1972.

By March 29, 1972, Riesman and his wife had returned to Princeton: “Whenever I go away on a trip I return, as you can imagine, to a mountain of mail, but in the case of Stockton, Evey and I returned full of stimulation and interest. A great deal of this was thanks to you; both personally and professionally your help, interest, considerateness, intelligence and outspokenness helped a great deal. Thanks so very much."

The tone changes slightly (what I mean is that Bjork seems more dependent on the views of Riesman) in a letter from Bjork to Riesman dated November 28, 1972:

I know that Dick [Chait] encourages you to visit us. I very heartily second that invitation, for I certainly would welcome an opportunity to visit with you. It would help a great deal in giving me additional perspectives on what we are doing. Sometimes Dick and I wonder who is sane and who is insane in the field of higher education. I realize that’s not peculiar to higher education, but very often we feel close to the lunatic fringe.

But Riesman’s attitudes about Bjork change in the book. Consider the following quotations:

Most presidents of liberal arts colleges come originally from the faculty and regard their former colleagues, in terms of personal relationships at any rate, as perhaps the most important constituency, to be befriended and protected against pressures or to be coaxed into yielding when that appears the only feasible course. To be sure, in times of retrenchment, and often at other times as well, faculty do not always reciprocate, and presidents feel betrayed, just as faculty feel betrayed by what they see as presidential expediency.

Bjork did not come into administration as a former professor, although he has done some teaching and at present gives a course called bureaucracy and public policy. Rather, he had begun as a Dean of students, a position in which one often sees the casualties created by sarcastic or even sadistic faculty, and in which one can often acquire, as many student counselors do, an anti-faculty perspective. Indeed, on his side, Bjork showed no interest in the faculty personally; and faculty felt their relation to him was simply that of an employee to employer. (333)

If Bjork bore down hard on the faculty to get them to be responsive to changing student demands, he was, as has already been suggested, no more protective of the academic deans. His view concerning both his deans and faculty has been that it is easier to fire people than to persuade them to change. He has not wanted to have collegial relationships with his “employees,” but has remained aloof, thus feeling free to use his power to hire and fire. In this situation he has been able to terminate courses and rearrange interdisciplinary programs with considerable flexibility, according to what he felt to be student demands.

Even if Bjork did seek to change his ways and to become more conciliatory, the faculty would not be likely to respond; the wall of distrust is now too high. Though all the state colleges voted to oust the NJEA and to install in its place an AFT union, the Stockton faculty’s overwhelming (95 to 1) vote in favor of the AFT can be taken in part as a vote of no confidence in the president. The latter is quite prepared to deal with the union, both locally and, as we have seen earlier, in statewide collective bargaining. As in many state and a few private institutions throughout the country, a “managerial” outlook has evoked an “employee” response. (337)

There is a certain irony in how quickly the faculty assumed a fairly well entrenched suspicion of and hostility toward Pres. Bjork — an attitude which goes somewhat beyond the widely prevalent faculty attitude toward administrators; one faculty member put it in terms of a conflict between “a radical president and an increasingly conservative faculty.” What was meant by this was that Bjork had taken literally the wish of many faculty who came to academic maturity in the 1960s to become “student centered” – interdisciplinary, flexible in their responsiveness to students. But now the faculty have waked up to the fact that the absence of departments means the absence of a hierarchy to operate as a buffer between themselves and the president. The faculty realize that the president is instantly accessible to students, including those who would want to complain about faculty inaccessibility; and while the president is accessible to the faculty as well, they have found him combative, sharp in response to criticism, and often opaque concerning future plans. (332)

And finally:

From the outset, Pres. Bjork has taken the position of the student as client or consumer: in his view, faculty members should be no more immune to the consequences of criticism for poor performance than any other supplier of goods and services. Bjork is prepared, if there is to be collective bargaining, to make tenure a negotiable issue along with salaries and workload.

The Evaluation Team Report of the Middle States Association (made in 1975) gently suggested that a different, less “managerial” style might now be useful in the president’s office, and cautioned college about what appeared to them to be “an excessive use of words such as ‘flexibility.’ “The report implied that the term might be useful as an image but was dangerous as a slogan, and that faculty was certainly likely to react to it in the latter way. Bjork is himself prepared to be evaluated — as a state civil servant, by the Board of Trustees, and by the Board of Higher Education and the Chancellor who will be selected to replace Ralph Dungen.

But it has become clear that Bjork is unlikely to change his ways. From his point of view, many faculty members are seeking to retain the “innovative” status quo created by Wesley Tilley in the first group of recruits. Those who hold this now traditional point of view, Bjork would say, are inattentive to the altered economic and cultural climate of the mid-70s, and its effect on state system funding and on student career aspirations. From the faculty member’s point of view, “flexibility” means heightened insecurity. Some of the often-imaginative General Studies courses may be pushed aside, for example, by marketing courses in the growing Program of Business Studies in the faculty of Professional Studies. Or, if the faculty of Arts and Humanities wins the right, now being sought in Trenton, to grant the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, other courses will be pushed aside to make more rule for studio or music courses. (336–37)

Hodgkinson

Shortly after Riesman’s visit, Harold Hodgkinson was interviewing Stockton’s faculty, students and administrators. Indeed, Riesman mentions the ensuing report from Hodgkinson in The Perpetual Dream. Hodgkinson was the premier scholar of data in the country. He is the author of twelve books, hundreds of articles, and served as editor for several journals.

In 1974, Hodgkinson published the results of his study of the College and its members. He pays special attention to Stockton’s “Democratic Governance Score,” finding that responses to his queries about governance state “that democratic governance is particularly low for students and faculty while administrators see the democratic governance of the campus in a more favorable light.”

Other questions he asked include:

Q: “In general, decision-making is decentralized whenever feasible or workable.”

A: On this question, 61% of the administrators strongly agree or agree whereas only 42% of the faculty and 37% of the students agree. Fifty-six percent of the faculty disagree or disagree strongly with the statement, suggesting that there is a real disagreement on campus as to the decentralized nature of decision-making.

Q: “Power here tends to be widely dispersed rather than tightly held.”

A: Eighty-eight percent of the faculty disagree or strongly disagree with that statement, and 75% of the administrators disagree or strongly disagree; while 76% of the students disagree or strongly disagree.

Q: “There is a long-range plan for the institution published for college wide distribution.”

A: 45% of the faculty say yes, 38% of the faculty say no; while 67% of the administrators say yes.

Q: “Most faculty consider the senior administrators to be able and well-qualified.”

A: 35% of the faculty agree or strongly agree with this statement, whereas 63% either disagree or strongly disagree. On the other hand, 63% of the administrators agree with the statement, and 35% disagree or strongly disagree.

Q: “Although they may criticize some things, most faculty seem loyal to the college.”

A: On this item, 85% of the faculty agree and 77% of the administrators agree.

Q: There is a strong return on a question regarding the existence of a sense of community on campus with feelings of shared purposes.

A: Fifty-seven percent of the faculty agree with that statement, and 51% of the administrators agree. On the other hand, faculty morale is low, as agreed to by 80% of the faculty and 65% of the administrators.

Hodgkinson’s work highlights the distrust, lack of support and divisions that existed soon after the College opened. The administration was heavy-handed, demanding, and suspicious of faculty intentions. The students were, generally, left out and ignored. It was not an environment destined for success.

The Union

Sometime around 1972, Wes Tilley — the Academic Vice-President — asked me to arrange meetings of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), NJEA and AFT for faculty. I contacted each group and arranged a time for them to present their organizations to the faculty.

The AAUP was the most traditional group. Stockton actually had a chapter of the AAUP started by Ralph Bean. Many faculty members had joined. The meeting with the AAUP was sane, responsible, full of information and appreciated by those who attended.

The NJEA was the current state-approved organization of the faculties of each State College. The NJEA also represented public school teachers and, therefore, seemed not to understand college-level faculties. The presentation was disorganized, unappealing and bereft of the information faculty wanted.

The AFT meeting was radically different from the other two organizations. It was raucous, lively and with plenty of appreciative clapping. It was clear that it was prepared to fight the State on all of the traditional issues: pay, working conditions, representation on administration decisions and the camaraderie of strongly felt concerns.

It was, therefore, no surprise that when Stockton faculty voted to be represented by the AFT, the vote was 95 to 1!

Hodgkinson had found clear evidence of faculty dissatisfaction with the administration and how it isolated the faculty when big decisions were made. The faculty strongly disliked the administration and saw that power was centralized and strongly held.

Riesman also noted the tough stand against sharing power on the part of the President. The President had written in June 1972 a critical document on promotion and tenure (rf. Administrative Working Paper IV) and was leading the other State college Presidents in the State’s collective bargaining efforts. Indeed, he argued that tenure should be abolished in a speech to New Jersey college Presidents.

In a July 10, 1973, letter to Riesman, Bjork mentions collective bargaining:

Collective bargaining stumbles along at the state level as usual. I’ve met on several occasions with the Chancellor and the Gov.’s staff. At the moment, it appears that a contract will be a long time in coming. Apparently, the state is willing to face the possibility of a strike. They will probably watch closely developments with CUNY and SUNY. In any case the state is getting much more aggressive and willing to take the initiative in proposing terms and conditions of employment. AFT which has a very slim hold on the state college faculties seems very anxious about their ability to maintain that control. I have a feeling that NJEA is waiting in the wings and probably will pounce next February which is the first time a new election can be called.

Riesman responds on July 23, 1970:

As you know from things I have said and written, I keep rather hoping that there will be a strike by faculty which will fail, so that the now very great momentum behind collective bargaining will taper off as it has in the general union movement in America. I had a comment from a young historian at Barnard College several days ago in which he said that faculty do not realize that when they go in for collective bargaining, they surrender the power they already have, which is most of the power, on the one hand to management and on the other to the bargaining agents. They think they will gain more power but in fact they will lose power.

Bjork agrees – August 7, 1973:

First, on the matter of unionization of higher education, I agree fully with the young Barnard historian you quote. This is an argument we have used in New Jersey for a long time. Obviously, to no avail. I feel strongly that faculty not only abdicate claims to directing the enterprise by unionization, but they also relinquish an impressive array of rights, privileges, etc. which made being a faculty member something very distinctive and important. I only wonder how many years it will take before this realization is strong enough to override the anxiety and paranoia which seem so prevalent in higher education these days. On the other side, these are promising days for administrative or management leadership if they choose to exercise it. Unfortunately, the most powerful force to move into the dominant position appears to be statewide departments and coordinating groups.

Riesman quotes a friend – August 22, 1973:

On unionization: I was talking just now to a friend who teaches sociology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst about the union movement there. He said that Bloomfield College’s fight with the AAUP has pushed a lot of previously conservative and anti-union professors into the union camp. I said I thought that was really odd because Bloomfield is suffering from public competition and can’t afford to survive, or barely can survive; it shouldn’t frighten the tenured professors at a major state university which is still growing in a state, which, like New Jersey is trying to catch up in public higher education.

In The Perpetual Dream, the union is a growing force in the background. When the College started, collective bargaining — what there was of it — was handled by the NJEA which seems to have prided itself for not being a union. But by 1973, unionism had great strength at Stockton: so much so that when the vote was taken between the NJEA and the AFT as representatives of the State College system, at Stockton the AFT won 95 to 1. The union was no longer lurking in the background; indeed, it called a strike the state in November 1974.

In the exchanges between Bjork and Riesman, the union is a force that will take power

away from faculty. Reading the letters, I have a sense that both men thought of the

faculty at Stockton ignorantly stepping off a cliff and neither man could stop that

from happening. Unionism, for both, is a dark force which will drain faculty power.

Perhaps they were right.

Conclusion

I started this essay believing I could read the correspondence between two men and, perhaps, two chapters of a longer text, and that, having closely read these texts, would understand both men. The result is that I only know them slightly more than I did. Dick Bjork and David Riesman are complex intellectuals with radically different responsibilities and, I suspect, radically different world views. Bjork was starting a college; no easy task under the best of conditions. Riesman was a famous scholar having spent his life thinking about relationships between people and institutions and whether the first can successfully shape the other. So, his question – as he investigated seven institutions of higher education — was whether humans shape institutions or institutions shape humans.

Bjork delegated this issue. In a very real way, Bjork did not “found” Stockton; instead he hired others to do so. Bjork was really not interested in either half of Riesman’s question. Rather, he had a more corporate view: the institution is provided for humans to effect change in students — in a very real way to “create” citizens. The process of creation is supreme in his thinking. If for some reason, the process isn’t working, one has to review/replace those working on the process. Or one examines the institution to see why it isn’t working in the process. The goal is to create citizens; whatever hinders that is to be expunged.