The President’s Cabin Fire

By Brendan Honick

The first president's office at Stockton State College, before the executive suite in K Wing existed, overlooked the northern shore of Lake Fred in a rustic log cabin. This cabin, and three others, had been built by previous property owners years before ground was broken for the Galloway campus. In the 1972-1973 academic year, the President’s Cabin seems to have represented a breaking point in on-going student and faculty protests: on the evening of February 21, 1973, when tensions reached a boiling point, it was set ablaze.

As the Galloway campus was being constructed, the growing administration needed places to work; they claimed some of the cabins on Lake Fred for their offices. In the essay “Providing Funds” in Reaching 40, the University’s 40th anniversary commemorative text, former Director of Financial Aid Jeanne Sparacino Lewis describes how her office made use of the unique setting. According to her, “The Office of Financial Aid was relocated to a log cabin on Lake Fred. The log cabin consisted of two professional offices, a bathroom, a kitchen, and a living area, which provided space for the clerical staff” (72). Although the cabins’ interiors were originally designed for home, not office use, they were functional: their proximity to one another (see the map) centralized several offices in one location. This grouping foreshadowed current administrative clusters at the Galloway campus, such as K and L Wings (e.g., the contemporary President’s Office) and the second floor of the Campus Center. The administration did not have sole use of the cabins for long; when students arrived, they used the cabins as places to hold mass services, run food co-ops, and gather for musical jam sessions. The plan for the President’s Cabin, before the fire, was eventually to convert it to a student lounge. Since the cabin was demolished soon after the blaze, this use never materialized.

In the 1970s, Stockton’s power dynamics were evolving. The administration, faculty, and students all wanted a say in how the school would be managed. President Bjork’s view was that he and the Board of Trustees held the most influence and the final say at the school: faculty and students were secondary. In December 1972, seven members of the founding faculty were not recommended for reappointment by President Bjork, a decision that would terminate their employment at Stockton. This was part of a new staffing and evaluation plan that Bjork and the Board of Trustees had developed without consulting with the faculty. Because professors were unhappy about the deterioration of shared governance (the collective shaping of Stockton), membership in the Stockton Federation of Teachers (SFT) union increased. Tensions between the administration and faculty were so high that, on February 13, 1973, the SFT called for Stockton to protest Bjork's decision: they argued that students and faculty were not being fairly represented. On February 21, the SFT voted to hold a moratorium on “business as usual.” The students voiced their concerns as well and although Bjork met with the Stockton Student Union (SSU) on February 21 to placate their concerns, that same day they voted to strike for shared governance. That night, an anonymous party set fire to the President’s cabin.

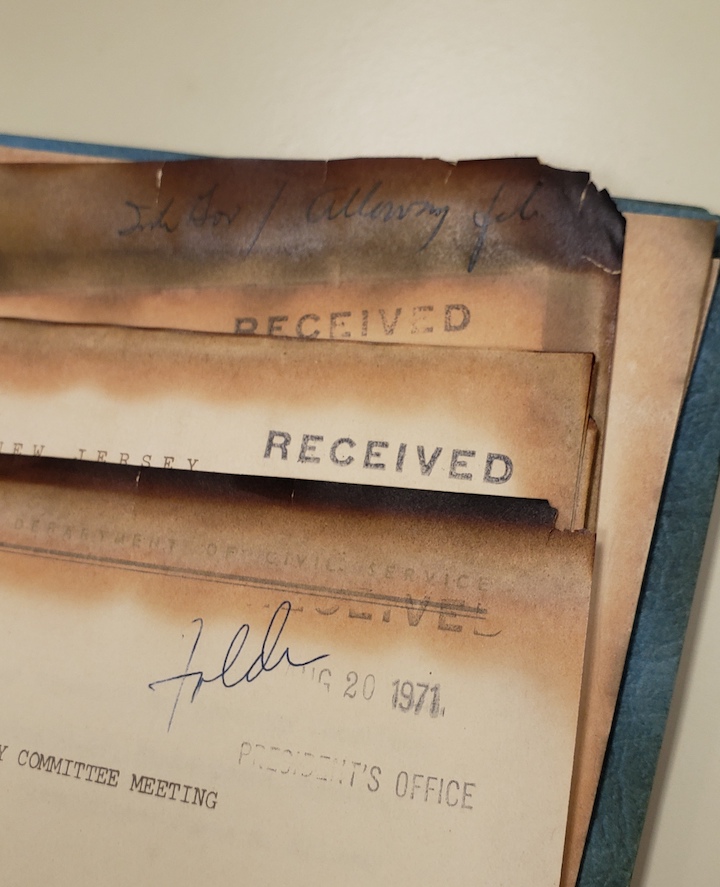

Although no person or group claimed responsibility for the fire, the news of the event spread far and wide (The New York Times reported on the fire on February 23). The February 28, 1973, issue of The Argo describes the destruction: “Extensive damage was reported in the secretarial area of the cabin. Also damaged severely was the offices of Chuck Tantillo and Joe Barritt. Richard Chait’s office and that of the presidents’ [sic] received less damage. The administration puts the loss in access [sic] of $50,000 as most of the equipment (desks, typewriters, cabinets, dictaphones etc.) was a total loss.” Although many of the office’s documents and folders were charred, they were preserved (they can still be found, singed, in Stockton’s Special Collections and Archives).

Both the SFT and the Student Union condemned the arson, yet the message, from this historical distance, seems clear: there were enough aggrieved parties on campus that someone deemed it necessary to send a message to Bjork and the Board of Trustees.

While the cabins on Lake Fred no longer stand, they are an important part of Stockton’s history. The blaze on the lake’s shore in 1973 highlights how contentious debates about Stockton’s governance were. Although few individuals working at Stockton today remember the fire, the event has had a lasting effect on the institution’s memory. The President’s Cabin, removed from the academic center of campus, symbolized a distancing between President Bjork and the students and faculty in the 1970s. The arson, perhaps, showed that Bjork’s decisions would not go uncontested. The actions of a few threatened the fundamental purpose of the College, but, fortunately, the result has merely become a memory.