Green Dot Bystander Intervention Program

Traditional prevention programs may only approach men as potential perpetrators and women as potential victims. Green Dot approaches all students, staff, administrators, and faculty as allies. The original Green Dot program was conceived in the college setting to prevent dating violence, sexual violence, and stalking. It relies on the premise that if everyone does their small part and commits to individual responsibility, the combined effect is a safe campus culture that is intolerant of violence. The college-based curriculum draws heavily on the experiences of college students and the reality of this issue in their lives. This curriculum uses interactive activities to reinforce core concepts and encourages students to envision their future and the world in which they want to live, then aligns their bystander behavior with that vision. (taken from Alteristic.org, creators of the Green Dot Strategy)

"Red dots are bad. Green dots are good."

This workshop teaches us how to effectively use Green Dot bystander intervention techniques to safely and effectively reduce red dot incidents of sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking in our community.

- identify warning signs of high-risk or potentially harmful situations

- identify personal obstacles that prevent them from intervening in high-risk or potentially harmful situations

- effectively demonstrate the direct, distract, and delegate strategies to reactively intervene in high-risk situations

- describe their responsibility as bystanders to step into situations they recognize as potentially harmful in whatever way they are able

- perform proactive Green Dots that communicate violence prevention is a value on the Stockton University campus

- understand that they are a part of a community where individuals reactively intervene in high-risk situations

- proactively work to transform social norms to show that violence is not tolerated in the Stockton University community

- demonstrate that everyone needs to play their part in keeping Stockton University safe

- Like our Instagram page @stocktongreendot to keep up to date on what’s happening on campus.Tell a friend of yours that ending violence is important to you.

- Add the phrase “Green Dot Supporter” to your Facebook or Twitter profiles.

- Using email, text, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat – send a mass message out to all of your friends that violence prevention matters to you, and give them a link to campus or community resources.

- Volunteer at your local domestic violence/sexual assault program.

- If you are concerned that a friend of yours might be a victim of violence, gently ask if you can help and respect their answer.

- Attend a program or event designed to raise awareness about violence.

- Create a fund-raiser for a campus or community organization that works to address violence.

- Look out for friends at parties or where alcohol is involved to ensure everyone arrives and leaves together.

- Work to bring an education program to your class or group.

- Hang a Green Dot poster on your door.

- Hang an “I’m Green Dot Educated” placard on your door.

- Like our Instagram page @stocktongreendot to keep up to date on what’s happening on campus.

- Talk to your coach about having a Green Dot training or overview speech for your team.

- If your whole team can’t attend a training, come to one of the open bystander trainings offered throughout the year.

- Talk to your coach about hosting a “Green Dot Game” to promote awareness about power-based personal violence and show your team’s commitment to ending it.

- Talk to your coach about adding a Green Dot to your uniforms to show your team’s commitment to ending violence.

- Watch out for your teammates at parties and bars.

- Wear a Green Dot pin or another pin or piece of clothing (could even be a coffee mug that you carry) that has a message of anti-violence. Sometimes just showing your support and commitment can make a big difference.

- Place a Green Dot on your office door so students know you support prevention and their efforts as bystanders.

- Hang a Green Dot poster in your office or classroom.

- Have local resources’ brochures visibly available in your office and/or classroom.

- Insert a related statement on your syllabus

- Have an endorsement statement of some kind attached to your email signature line, such as “I’m a green dot supporter.” or “What’s your green dot?”

- Have link to your local service providers’ websites on all the web pages over which you have influence. (See the bottom of the page for local resources.)

- Three times per semester, simply ask your classes “What green dots have you done or seen lately?” Research tells us that this simple task provides significant reinforcement of green dot behaviors.

Role Model

- Role model respectful language, compassion toward survivors, approach-ability, and looking out for others.

- Ask your department head or supervisor to bring a bystander training to your whole department.

- Have a conversation with your colleagues and students about what they can be doing to spread green dots.

- Where appropriate, bring educational programming on interpersonal violence to your classes.

- Where appropriate, include topics in your classes that address prevention and intervention of partner violence, sexual assault, stalking and bullying.

- Make it clear to your students that if they are dealing with violence, you are a safe person to approach for support and referrals.

- Become familiar with campus and community resources, and make referrals if needed.

- Consider conducting research that furthers our understanding of violence prevention.

- Assign readings or papers or journal topics on the issue of power-based personal violence.

Build relationships

- Build positive, trusting relationships with students; particularly those who may be experiencing violence or other adversities outside of class. (See section on being a, "Responsible Employee" with Title IX reporting)

Collaborate

- Use your relationships and departmental or interdepartmental partnerships to discuss ways in which to support students as bystanders, support survivors, and improve safety for positive outcomes in the classroom.

Share your own experience

- Create an opportunity to share your own experience as a bystander and how it made you feel, then and now. Or, you may have had a situation when you were at risk and someone did or didn’t help. You may have been in a situation where you saw something and did or didn’t help. Sharing your own experience will help your students process their experiences and become more active bystanders.

Talk to your students about being active bystanders. Talking points for student bystanders:

- The choices you make matter.

- You’re not a bad person because you don’t always get involved.

- There are a lot of options. You don’t have to do something directly. It’s best to pick the option that is best for you, depending on the situation and what’s coming up for you.

- What makes it hard for you?

- This is what makes it hard for me…

- What are ways of intervening that feel realistic to you?

- Recognize risk factors associated with violence and ensure that faculty, staff, and students are provided with adequate training to respond.

- Ensure adequate funding for prevention and intervention efforts.

- Talk with colleagues about your personal commitment to violence prevention and Green Dot.

- Integrate references to the Green Dot initiative and the importance of violence prevention into speeches and public addresses.

- Educate yourself and your staff about sexual violence, partner violence, stalking and abuse.

- Bring Green Dot training to your next staff meeting, organization meeting or retreat.

- Ensure that you have effective policies in place to assure safety in the workplace and support victims of violence.

- Ask a man in your life about the impact personal violence has had on him or on someone he cares about.

- Ask one male friend or relative what he thinks about power-based personal violence and what men could do to help stop it.

- Understand that men can experience sexual violence, too.

- Tell a woman in your life that conquering power-based personal violence matters to you.

- Ask women in your life about the impact power-based personal violence has had on them.

- Ask a woman in your life what you can do to help take a stand against violence.

- Have one conversation with one male friend or relative about Green Dot.

- Have a conversation with a younger man or boy who looks up to you about how important it is for men to help end violence.

- If you suspect someone you care about is a victim of violence, gently ask if you can help.

- Google “Men Against Violence” and read what men around the country are doing.

- Look out for friends in places where alcohol is served to ensure that everyone arrives and leaves together (not alone).

- Create a fund-raiser for a local organization that works to address violence.

- With two male friends, attend a program or event designed to raise awareness about violence.

- Attend a Green Dot Bystander Training.

- Change your e-mail signature line to include the statement, “Live the Green Dot” and include the link to our Green Dot website.

- Donate to a local rape crisis center or domestic violence shelter and write “Green Dot Supporter” in the memo line.

- Hang one of our Green Dot posters on your room or office door.

- Put a link to campus or community resources on any website you have access to.

- Send a mass e-mail to your contact list with a simple message like, “This issue is important to me and I believe in the goal of reducing violence on campus.”

- Next time you are walking to class with a friend or taking a lunch break with a co-worker, have one conversation about Green Dot and tell your friend that ending violence matters to you.

- Add the phrase “Ending violence one Green Dot at a time” to your Facebook or Twitter account.

- Make one announcement to one group or organization you are involved in, telling them about Green Dot.

- Write a paper or do a class assignment on violence prevention.

- Wear a Green Dot button and be willing to explain Green Dot to anyone who asks.

Summary: Major Bodies of Research that Inform the Green Dot Strategy

Given the extraordinary human cost of failure, we must inform every aspect of what we do with the most current science, then divest personal ego and scrutinize our work with objectivity and scientific rigor, course correcting each step of the way. A partial summary of the major bodies of theory and research that inform the central tenets of Green Dot is provided below.

Violence Against Women

A review of the literature within the field of violence against women suggests that despite years of sustained effort, we have not yet realized a measurable reduction in violence. However, an examination of the outcome/evaluation research does provide some clear indicators of prevention strategies that have not been effective. For example, a meta-analysis of sexual assault education programs conducted by Anderson and Whiston in 2005 found that traditional awareness programming in the form of one-time only educational sessions, large-scale events and the dissemination of printed educational materials – are not effective means to reduce violence. Traditional program content, including facts, statistics, myths, and definitions have also failed to demonstrate a decrease in violence. These types of approaches have demonstrated success at increasing basic knowledge, as well as some success at improving violence related attitudes, particularly in the short term. These approaches have also had some success in increasing utilization of direct services (Anderson & Whiston, 2005). There is little to support prevention programming that focuses exclusively on risk reduction targeting women, and there has been little demonstrated effectiveness in approaching all men as potential perpetrators with messages related to obtaining consent.

Application to Violence Prevention: Stop doing what doesn’t work. Stop calling “awareness education,” “prevention.” Look outside our own field for potential applications of successful prevention strategies from other disciplines.

Bystander Literature

Within the field of Social Psychology, there are decades of research documenting basic principles of bystander behavior that have a broad impact on individual and group choices. This body of research seeks to understand why individuals choose to intervene or remain passive when they are in the role of a bystander in a potentially risky, dangerous or emergency situation. The current body of knowledge demonstrates bystander influences such as: (1) diffusion of responsibility – when faced with a crisis situation, individuals are less likely to respond when more people are present because each assumes that someone else will handle it (Darley & Latane, 1968; Chekroun & Brauer, 2002); (2) evaluation apprehension – when faced with a high risk situation, individuals are reluctant to respond because they are afraid they will look foolish (Latane & Darley, 1970); (3) pluralistic ignorance – when faced with an ambiguous, but potentially high-risk situation, individuals will defer to the cues of those around them when deciding whether to respond (Clark & Word, 1974; Latane & Darely, 1970); (4) confidence in skills – individuals are more likely to intervene in a high-risk situations when they feel confident in their ability to do so effectively; (5) modeling – individuals are more likely to intervene in a high risk situation when they have seen someone else model it first (Bryan & Test, 1967; Rushton & Campbell, 1977). These well-documented principals not only suggest what inhibits bystanders from intervening, but also, strategies for effectively overcoming these inhibitions and increasing the proactive and reactive responses of bystanders.

Application to Violence Prevention: The bystander research provides the targeted behavior we want to endorse. The behaviors include actively intervening in situations that are imminently or potentially high-risk for violence, as well as effective means to elicit that targeted behavior. Further, this body of research provides specific strategies to increase the likelihood that the trained individuals will actually intervene when they are in the role of a bystander.

Diffusion of Innovation/Social Diffusion Theory

The social diffusion theory (Rogers, 1983) is based on the premise that behavior change in a population can be initiated and then will diffuse to others if enough natural and influential opinion leaders within the population visibly adopt, endorse and support an innovative behavior. Based on this model, early adopters of any given population are systematically identified, recruited, and trained to serve as behavior change “endorsers” within their community and sphere of influence, resulting in a shift in the targeted attitudes and behaviors within that community. In other words, opinion leaders shape social/ behavior changes by making it easier for others to initiate and maintain certain “new” behaviors. Diffusion of innovation theory and the influence of early adopters to establish new behavioral trends has been studied extensively for decades and proven widely successful across settings and content areas (Kelly, 2004). For example, Kelly et al. (1997) has demonstrated the effectiveness of training early adopters in increasing safe sex practices among populations of gay men. One study targeting gay men in four cities implemented five, weekly training sessions and found at the one-year follow-up an increase of more than 25% in condom use. Additionally, Sikkema (2000) focused on safe-sex practices among impoverished, inner-city women. At the one-year follow-up they found a 12.5 % drop in unprotected sex and an increase of 17% in condom use. The strength of the community-wide behavior shift was further demonstrated; in populations where changes were made – the population still demonstrated the documented improvement at the three-year follow-up (despite that the actual intervention had ceased within the first year). Though there is evidence that over-use or misuse of early adopters can backfire, an appropriate utilization of Social Diffusion Theory has been consistently demonstrated to be an effective and efficient method for creating culture change.

Application to Violence Prevention: Given that sexual, domestic and stalking violence in our communities exists on a scale that clearly reaches the scope of a public health concern that requires broad-based, community level change, it is imperative that a critical mass of individuals endorse and engage in targeted behaviors that are proactively and visibly intolerant of violence. Since few organizations have the resources to provide direct training to enough individuals to obtain this critical mass, strategically targeting the most socially influential individuals becomes necessary, as these “popular opinion leaders” can then most effectively and efficiently impact the attitudes and behaviors of their peers through modeling, endorsing and engaging in the targeted behaviors. Furthermore, social diffusion theory suggests that we take an approach different from the peer education and mentoring models we have historically used, finding that peers are most influential in their natural, social environments rather than when placed in paraprofessional roles.

Marketing / Rebranding Research

Rebranding of corporations, organizations and services is a process that has been well examined and documented within marketing research. A smart rebranding strategy allows an entity the chance to meet the needs of consumers and investors, and is most often prompted by a gap between the espoused brand, and the actual brand image that others may have or under performance toward meeting the organization’s goals (Davies and Chun, 2002; Kapferer, 1997). When engaging in a rebranding effort, key issues include: focusing on how the brand should be changed, weighing the potential costs and benefits of a brand change, and understanding and addressing internal resistance that key stakeholders may have to the change (Merreilees & Miller, 2008). In addition, it is essential to carefully and thoroughly review an organization’s mission, vision and values – then, redefine in a way that translates into an image that is relatable to the targeted audience and sensitive to the customer base (Ewing et al., 1995). Finally, marketing literature emphasizes the need to re-vision the brand based on a solid understanding of the consumer, to meet both existing and anticipated needs (Merreilees and Miller, 2008). Though a rebranding effort can involve considerable commitment, the research is full of examples of companies that were able to revitalize their products, reputation and consumer buy-in through this process.

Application to Violence Prevention: The evidence is clear and consistent that there is a significant gap between the espoused “brand” of violence against women prevention (i.e., inclusive, want men to join the movement, urgently relevant to all of us) and the brand perceived by the community (i.e., manhating, choir-only, not their issue). Despite our best intentions, this branding crisis is resulting in the violence against women prevention movement remaining a largely choir-based, women’s-only movement that has gained little traction in terms of broader community support in the past several decades. By better understanding and addressing the explicit and implicit concerns of the “consumer” (community members we are trying to engage), we can reposition ourselves in a way that will reduce the barriers that prevent more from joining prevention efforts. Another key application of the marketing research involves the importance of working closely with key stakeholders (i.e., current educators, advocates and direct service providers) to ensure they are fully engaged and supportive of the rebranding and any pockets of resistance are addressed (Merreilees and Miller, 2008).

Perpetrator Data

There are growing bodies of research that give insight into the behaviors and patterns of perpetrators. Research on batterers demonstrates the mechanisms most often used to exert power and control over a target – from the earliest warning signs to the most extreme forms of violence (Johnson et al., 2006). Literature examining the behaviors of sexual offenders, particularly offenders known to the victim, gives profound and clear insight into their patterns – including how they target, assess, isolate, and coerce a victim (Lisak & Roth, 1988; Lisak & Miller, 2002). This same body of research tells us that most sexual offenders repeatedly commit this kind of violence and suggests that their actions do not involve a lack of clarity about consent (Zinzow & Thompson, 2014; Abbey & McAuslan, 2004; Lisak & Miller, 2002).

Application to Violence Prevention: If Social Diffusion Theory speaks to “who” and Bystander Theory speaks to “what,” then understanding how perpetrators operate in targeting, assessing and victimizing speaks to the “how.” Because the proposed model seeks to engage bystanders in active intervention when they see a high-risk situation, the perpetrator literature is valuable in clearly delineating what constitutes a potentially high-risk situation. By knowing what a perpetrator is likely to do, a bystander can be alerted to behaviors that require intervention. Additionally, given what we know about offender patterns, clarifying consent is not an approach likely to reduce the incidence of assault.

Public Health

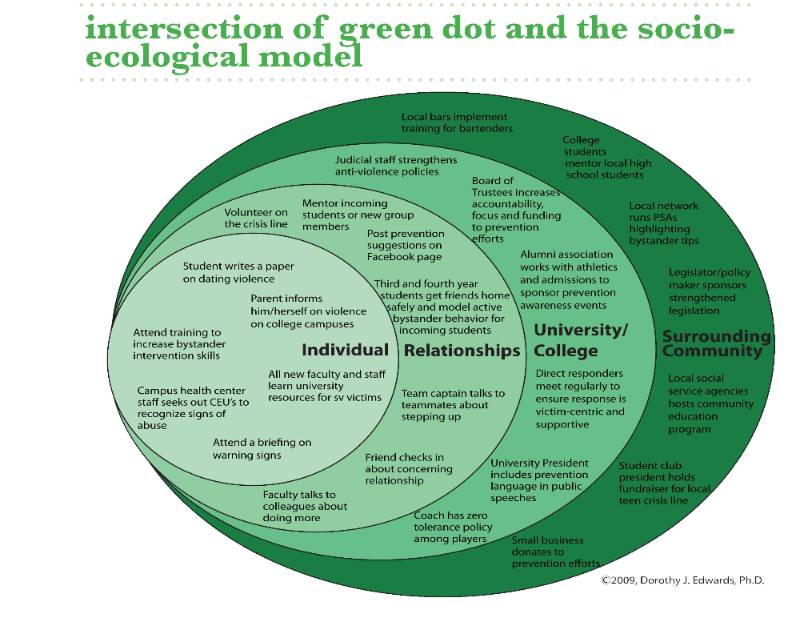

Violence can be understood as an adverse health condition given its multiple, negative affects on physical and psychological wellbeing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Public health frameworks for prevention hold promise for violence reduction because they have proven their ability to address and eliminate negative conditions that foster health problems (Prothrow-Stith, 2010). The World Health Organization (2010) contends that prevention of adverse health conditions requires action at each of the four, interrelated spheres of the social ecology:

Application to Violence Prevention: Work in addressing other public health issues clearly indicates that an effective prevention strategy is going to include addressing aspects of the issue that intersect with each level of the social ecology – including the individual, relationship, community and society levels. Green Dot’s broad lens of “bystander” incorporates individuals with the ability to impact not only a high risk situation at a party – but also individuals with decision making power that can impact policies, enforcement, and resources.

Adult Learning

Research in the field of androgogy (methods or techniques used to teach adults) clearly tells us the best ways to ensure individuals learn and retain the knowledge and skills necessary to engage in and endorse a new behavior or set of behaviors. Key components of effective androgogy include: emotion, repetition, varied instructional methods, connection with previous knowledge, consideration of attention span limitations, and harnessing intrinsic motivation (Knowles, 2011; Laird, 1985; Dirkx 2001; Keating, 1994; Pike, 1989). Furthermore, it is imperative that adult instruction focus on the learner (i.e., how students learn affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively), the instructor (i.e., the skills and strategies necessary for effective instruction), and the meaning exchanged in the verbal, nonverbal, and mediated messages between and among instructors and students (Mottet & Beebe, 2006). Components of effective instructional communication include: motivation, humor, immediacy, clarity, and content relevance (Aylor & Opplinger, 2003; Richmond, Lane, & McCroskey, 2006; Chesebro, 2002; Keller, 1987). Educational products should also seek to ensure that knowledge and skills attained in the training context are applied to learners’ jobs and other community responsibilities (Broad, 1997). An effective training engages and motivates learners, obtains stake-holder buy in, facilitates the transfer of information from short-term to long-term memory, and in many cases, brings about new behavior (Reeve, 2005; Ericsson et al., 1993).

Application to Violence Prevention: Given the pervasiveness of violence, prevention requires nothing short of a cultural shift. In order to shift culture, we need a critical mass of people to engage in a targeted behavioral change which requires that we design and present maximally effective educational products. Green Dot applies the principles of androgogy in both our instructional design and our facilitation in the learning environment. Furthermore, Green Dot is premised on the notion that the messenger matters and as such is designed to maximize the effectiveness of prevention educators. Given the stakes of this issue, it is imperative that anyone delivering a violence prevention program demonstrate exceptional ability in the area of education. For this reason, the Green Dot strategy utilizes a train-the instructor rather than a train-the-trainer design.

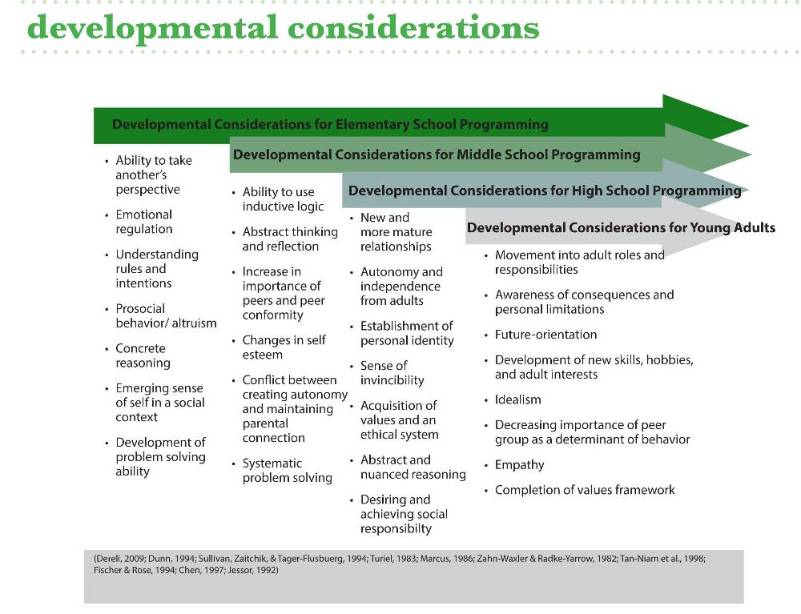

Developmental Psychology

In order to be effective, programs intent on behavioral change must align with the developmental capacities – socially, emotionally and cognitively – of individuals across the lifespan. The field of developmental psychology helps us understand and adapt to the unique needs and abilities of individuals at varying formative stages. A bystander-based approach to addressing conflict, aggression, and intergroup discrimination requires a number of age appropriate considerations:

Application to Violence Prevention: Early to middle childhood provides a window of opportunity to introduce the role of “pro-social bystander” and the corresponding script that accompanies it. Just as a child comes to understand and embody the “student” role, the hope is that the role of pro-social bystander will become internalized and an integrated part of the child’s evolving identity. In early adolescence, middle school students have the capacity to benefit from a bystander perspective because:

- they can consider other people’s feelings and perspectives, and

- they have the cognitive capacity to engage in problem solving.

While individual self-esteem is beginning to emerge, it is largely shaped by the influence and response of peers. Therefore, Green Dot does not rely on the ability of individual students to “take a stand” against their peers. Though explicitly negative peer pressure is less prominent for most kids, the need for conformity is high. Therefore, the goal of Green Dot for middle school students is to create behavioral options that would allow them to “do the right thing” while minimizing the need for them to stand-out from their peers. As peer conformity is of paramount importance during this stage, engaging peers with greatest influence as role models allows the program to harness the power of peer pressure, rather than fight against it. As students age, the Green Dot program for high school students is designed to tap into the establishment of personal and social responsibility, asking students to develop personal creeds and to identify self-defining moments when they have the power to make their communities safer. Because students at this developmental stage tend to feel invincible, Green Dot does not ask that they identify themselves as potential victims of violence nor does it threaten students with punishment if they fail to intervene or if they engage in risky behavior. Rather, Green Dot puts each student in the role of pro-active bystander with the power to shift social norms. At the college and community levels, Green Dot engages adults in honest and open conversations about barriers to action and realistic solutions. Green Dot is infused with hope for a different future where violence is not inevitable, helping individuals understand how their individual choices can have a lasting, positive impact.

Bibliography

The Green Dot etc. Prevention Strategy is built on the theory and research of key scientists from across disciplines. Hundreds of published articles have been gleaned for the best data available in order to construct the strongest possible attempt at prevention. While much of the work is cited within the curriculum, the brilliant work that heavily informs this programs includes that of V. Banyard, E. Plante, and M. Moynihan in the area of bystander intervention; the work of Stephen Thompson and David Lisak in the area of understanding perpetrators; and the work of J.A. Kelly and E. M Rogers in the area of social diffusion. A comprehensive bibliography is forthcoming. Key articles are listed below.

Bystander Literature:

Berkowitz, A.D. (2002) Fostering men’s responsibility for preventing sexual assault.

in P.A. Schewe (Ed), Preventing violence in relationships: Interventions across the

life span (3rd Edition). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (Chapter

7, pp. 163-196).

Katz, J. (1995). Reconstructing masculinity in the locker room: Mentors in Violence

Prevention. Harvard Educational Review, 65, 163-174.

Katz, J. (1994, 2000). Mentors in Violence Prevention Playbook.

Kilmartin, C. & Berkowitz, A. (2001). Sexual assault in context: Teaching college

men about gender. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Banyard, V.L., Plante, E.G., Moynihan, M.M.

(2004). Bystander Education Bringing a Broader Community Perspective to Sexual Violence

Rrevention. Journal of Community, 32, 61-79.

Moynihan, M. M., Banyard, V. L., & Plante, Elizabethe G. (in-press). Preventing dating

violence: A university example of community approaches. In Kendall-Tackett, K. and

Giacomoni, S. (Eds.) Intimate Partner Violence. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute.

Moynihan, M. M., & Banyard, V. L. (in press). Community responsibility for preventing

sexual violence: A pilot with two university constituencies. Special thematic issue

of Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community.

Banyard, V. L. (in press). Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior:

The case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims.

Banyard, V. L., Moynihan, M. M., & Plante, E. G. (2007). Sexual violence prevention

through bystander education: An experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology,

35, 463-481.

Banyard, V. L., Plante, E., & Moynihan, M. M. (2004). Bystander education: Bringing

a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community

Psychology, 32, 61-79.

Diffusion of Innovation Literature

Kelly, J.A. (2004). Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: Resolving

discrepant findings, and implications for the development of effective community programmes.

AIDS Care, 16, 139-150.

Kelly, J.S., Murphy, D.A., Sikkema, K.J., McAuliffe, T.L., Roffman, R.A., Kalichman,

S.C. (1997). Randomized, Controlled, Community-level HIV- Prevention Intervention

for Sexual-Risk Behaviors among Homosexual men in US cities. The Lanret, 350, 1500-1505.

Sikkema, K.J., Kelly, J.A., Winett, R.A., Solmon, L.J., Cargill, V.A., Roffman, R.A.,

McAnliffe, T.L., Hechman, T.G., Anderson, E.A., Wagstaff, D.A., Norman, A.D., Perry,

M.J., Crumble, D.A., Mercer, M.S. (2000). Outcomes of a Randomized Community-Level

HIV Prevention Intervention for Women Living in 18 Low Income Housing Developments.

American Journal of Public Health, 90(1), 57-63.

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovations. Valente, T. V. & Davis, R. L. (November

1999). Accelerating the Diffusion of Innovations Using Opinion Leaders. 55-67.

Perpetrator Literature

Koss, M.P., Leonard, K.E., Beezley, D.A., Oros, C.J. (1985). Nonstranger Sexual Aggression:

A Discriminant Analysis of the Psychological Characteristics of Undetected Offenders.

Sex Roles,12, 9-10.

Lisak, D. & Miller, P. M. (2002). Recent Rape and Multiple Offending Among Undetected

Rapists. Violence and Victims, 17(1), 73-84. Lisak, D., Roth, S. (1988). Motivational

Factors in Nonincarcerated Sexually Aggressive Men. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 55(5), 795-802.

Rapaport, K. & Burkhart, B. R. (1984). Personality and Attitudinal Characteristics

of Sexually Coercive College Males. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 2(2), 216-221.

(c) 2014, Dorothy J. Edwards, Ph.D. – used with permission